Vision and Change | Fermentation as Metaphor

I am deeply devoted to my practice of fermentation. In my home at this moment, I’m tending two long-term sourdough starters, one wheat and one rye, along with yogurt, and jun, a cousin of kombucha; periodically I dip into large vessels filled with half a year’s supply of kraut and kimchi while I wait for misos and shoyu and doubanjang and mirin and takuan and salo and saké and various country wines and meads to slowly ferment. In this realm there is a lot of waiting.

As my personal obsession with the microbial transformations of foods and beverages developed into books and a career as a fermentation revivalist, I have continued to ferment and learn and experiment in my home kitchen. I have had the great privilege to teach in many different parts of the world, and my travels have enabled me to taste and see incredibly varied fermented foods and beverages from wildly diverse cultural traditions, endlessly fascinating (and delicious).

Yet the more I ferment, and the more I think and talk and learn about fermentation, the more I realize that what is even more exciting to me about fermentation than its practical manifestations is its profound metaphorical significance.

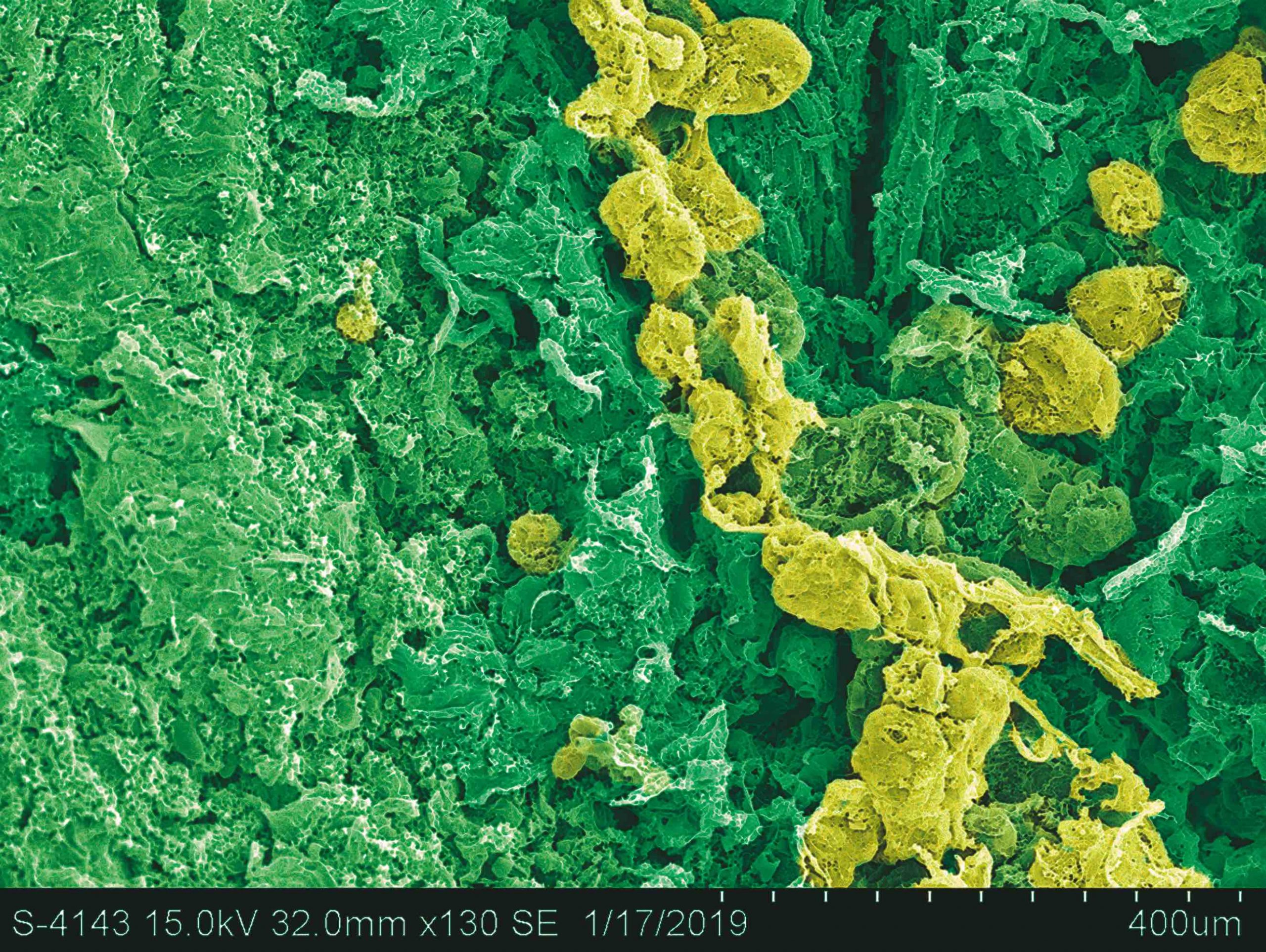

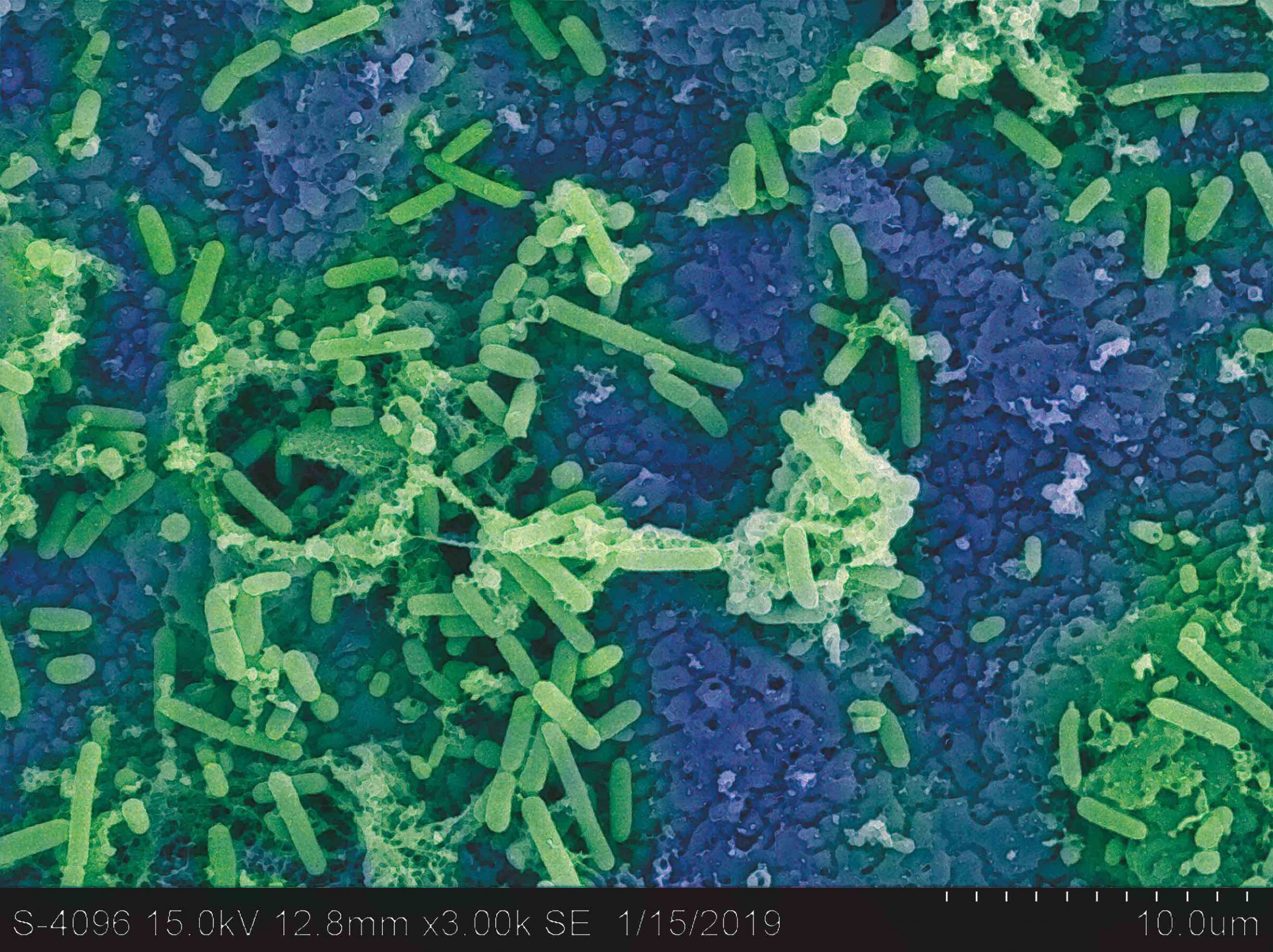

The English language uses the word fermentation to describe not only the literal phenomenon of cellular metabolism that it is—microorganisms and their enzymes digesting and transforming nutrients—but also much more broadly to indicate a state of agitation, excitement, and bubbliness. The expansive metaphorical possibilities of fermentation arise from the etymological roots of the word, from the Latin fervere, which means “to boil.” Long before the relatively recent scientific understanding of fermentation in the late nineteenth century as the work of bacteria and fungi, it was widely recognized by the bubbles that it (generally) creates. Therefore, anything bubbly, anything in a state of excitement or agitation, can be said to be fermenting.

According to the venerable Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest documented figurative use of the word fermentation in a surviving document comes from a Bible commentary, circa 1660, titled The Treasury of David, and is rather lurid: “A young man . . . in the highest fermentation of his youthful lusts.” And nearly as early, the term was applied to religious devotion, in this 1672 citation: “The Ecclesiastical Rigours here were in the highest ferment.” A 1681 political analysis observed: “Several Factions from this first Ferment, Work up to Foam, and threat the Government.”

Fermentation is extremely versatile as a metaphor. Inside our minds, frequently, ideas ferment as we think about them and imagine how they might play out. Feelings too can ferment, as we process them and they move through us. Sometimes this interior ferment transcends our individual experience and grows into a broader social process. In metaphor, as in the biological phenomenon, there is nothing that cannot be fermented. For decades now as a reader, ever since I began taking note of all things fermented, I have noticed in writing many varied metaphorical uses of the word ferment. “In the musical ferment of the late ’60s, influences were coming from every direction,” according to one article. “In the 1920s, Punjab was in religious ferment,” stated another. An artist’s obituary noted that he arrived in New York in 1955 and “was quickly swept up in the artistic ferment of the time.”

Certainly no particular ideology has a monopoly on fermentation. Intellectual, social, cultural, political, artistic, musical, religious, spiritual, sexual, and other forms of bubbly excitement are part of the range of human experience. In any realm of our lives, it is possible to get caught up in a feeling of shared effervescence. We should all be so lucky. Whatever the context, like its literal twin, metaphorical fermentation is an unstoppable force that people everywhere have harnessed, and gotten caught up in, in all sorts of different ways.

Fermentation can be driven by hopes, dreams, and desires; or by necessity, desperation, and anger; or by other forces altogether. Fermentation is always going on somewhere, though generally not everywhere. Sometimes in its absence it can seem elusive.

But when metaphorical fermentation occurs, it often spreads, transforming what was into what’s next. Fermentation is no less than an engine of social change.

As a force for change, fermentation is relatively gentle. Bubbles are not flames. Contrast fermentation with that other transformative natural phenomenon: fire. Fire destroys whatever lies in its path. Fermentation is not so dramatic; its transformative mode is gentle and slow. Steady, too. Driven by bacteria that spawned all life on Earth and continue to be the matrix of all life, fermentation is a force that cannot be stopped. It recycles life, renews hope, and goes on and on.

From my perspective, fermentation is generally a good thing, in both its culinary manifestations and its metaphorical ones. But just as some people fear and revile the strong recognizable flavors and aromas of certain fermented foods, or even the idea of them, others think the world would be a better place if everyone understood and accepted their role in it, and didn’t ask too many challenging questions; in other words, if bubbliness, agitation, and fermentation were minimized. Also, hateful and corrosive ideas can result from bubbliness and agitation, just as social justice can. The mass protests against racism and police brutality are examples of fermentation, but so is the surge of racism and anti-immigrant xenophobia around the world, and people feeling increasingly emboldened to give public expression to white supremacist ideas. Fermentation is a force that cannot be controlled, and the changes it renders are not always desirable. Even so, the metaphorical ferment is an unending source of new ideas, dynamic energy, and inspiration, and our best hope for regeneration.

“What fermentation shows us is the invisible connections of everything,” writes Mercedes Villalba in her Fervent Manifesto. “You learn to cultivate the future.”

The above excerpt is from Sandor Ellix Katz’s new book Fermentation as Metaphor (Chelsea Green Publishing, October 2020) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.