Can We Measure Culture and Consciousness?

featured photo by Phil Clothier

Kosmos | Phil, I was just remembering what you told me—that your parents ran children’s’ homes in the UK when you were growing up. So you had, quite literally, about 350 foster brothers and sisters. I have been trying to imagine this idea of a ‘new child’ arriving, likely with a very unique set of needs and wants. And I can’t help but wonder what that was like for you.

Phil | You’ve actually made me feel a little tearful as you say that. Has brought something up for me. There really was a lot of suffering. We saw children who were coming from broken homes, and often had feelings of trauma and abandonment. Some just curled up and wanted their own space. Some were very ‘clingy.’ It would be a process for my parents and the other kids in the house to receive them and allow them to be where they are, and gently break down those barriers to find out what they need.

Kosmos | Do you see any connection between this experience and why the Barrett model inspired you so profoundly when you first encountered it? This idea of aligning with group values and what happens when certain needs do not get met within the family or group. Can you see any connection there?

Phil | Yes, absolutely. In fact, my first two experiences with Richard Barrett’s model—one was reading his book. It was truly a mind-blowing moment for me and provided a form of language for all the feelings in my heart that I never knew existed. And the second was, I took the Personal Values Assessment and Richard Barrett fed back the results. I remember very clearly one of my values was the value of ‘being liked,’ which Richard considered potentially limiting. I said, “How can being liked have a limiting side to it?” Richard replied that, if being liked is more important than having integrity then you might do things in order just to be part of the crowd. And in that moment I saw times in my life that I had overstepped my integrity in order to belong and to be liked. It was a massive aha moment for me actually.

Kosmos | And Tor, tell us a little about your childhood.

Tor | I grew up in Sweden in a family with a lot of love and appreciation. I had a very loving and caring childhood, but I also have a picture I sometimes use when I introduce myself. That I am actually in a cage. I am in the cage because I was a super active, hyperactive kid. And I woke up my parents very early. So my dad kind of made a cage for me out of my bed. He literally locked me in this bed that was screwed to the floor so that I didn’t wake everybody up at three, four o’clock in the morning.

I also recognize that this has actually haunted me throughout my life. Not the fact that I was caged exactly, but the fact that I had this super activity and was not present. And in order to be a good child in school and all that, you need to be present in a way that I wasn’t. So I taught myself during my childhood that I am not smart. I’m not as intelligent as others.

The Barrett model has helped me to realize that I also was always wanting to show that I am good. Level 3 performance, so to speak. And in my professional life, I worked long hours. I worked 80 hour weeks. And in order for me to contribute to the world today, I needed to let go of that fear of not being good enough and just open up and share who I am. Richard Barreyt gave me the language—how we can actually talk about our development psychologically, and from a needs perspective.

If you are Level 1, having fear of not getting food on the table, then you have difficulties to liberate your soul—Level 5. If you’re having difficulties with relating—level two—then you’re going to have difficulties with the other levels. In my case, it was very much Level 3. I was afraid of not being good enough. That held me back from truly giving back to the world so to speak. We all have wisdom. It’s just that that was holding me back. So that’s kind of my relationship and my journey with the seven levels, and my childhood.

Phil | There are three underlying fears, which are the buckets for all the other fears that exist. It’s really important that we understand those. So at Level 1, which is the survival level. The fear is, “I don’t have enough.” I don’t have enough food, money, shelter, the basic stuff in order to feel safe within my physical existence. The second one is expressed as “I am not loved enough.” That was really my biggest one.

And the third one is very simply, “I’m not enough” or you could say I’m not good enough. Every human fear is actually a subset of those three basic things. That is what holds us back from fulfilling our own lives, creating great relationships, creating wonderful careers, creating the community we want to live in, and ultimately what holds humanity back from the big job right now, fulfilling the SDGs.

Kosmos | Thank you for sharing these very personal stories. So please tell us more about the Barrett model.

Phil | The Barrett model allows you to measure the culture and consciousness of any human entity from a single person an organization, and even a whole nation. The framework was developed by Richard Barrett by bringing together Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs with the Indian Vedic tradition. It allows us to make the invisible aspects of culture, (challenges, needs, desires, and priorities) visible as a start point for powerful new dialogue towards healing and transformation of any human system. It has been used by approximately 8000 organisations and governments in over 100 countries and is translated into more than 60 languages.

The model is a modern application of the chakra system applied to teams, organisations, communities, governments, and nations. You can try this yourself with a free Personal Values Assessment. www.valuescentre.com/pva

Kosmos | The Barrett model seems very much about alignment and integration. Can you show us a case study and a situation that you’ve gone into where there’s been disconnect and how was it mended? What was the process?

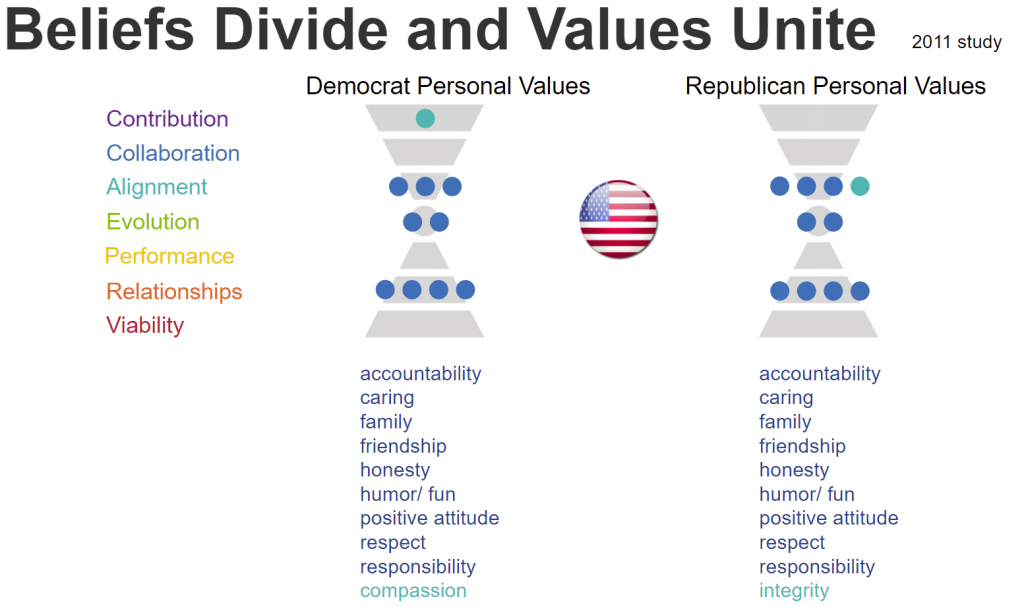

Phil | So I’ve got two to share with you. This one is something that’s very much in the process of not being healed yet. There’s a lot of work that’s necessary here, but this is a value assessment for the USA. And this is the first question, “what are the things that most reflect who you are?” And when we cut the data by those people who were Democrat and those people who were Republican, we actually saw that nine out of the top 10 values in 2011 were exactly the same. They’re in a slightly different order, but the only difference here is that Democrats prioritize the word compassion in their list, and Republicans prioritize the word integrity.

Phil | We say, ‘beliefs divide and values unite.’ Beliefs operate at this level up here—in the mind, but values operate much more on a heart and soul level. And when we can be in dialogue at a values level, we really start to discover what’s important to our hearts. We can connect to people. A real example of this would be in Latvia where there was big division of racial tension between the native Latvians and the Russians living in Latvia. And they brought together a Latvian teenagers and Russian teenagers to really talk about how they would reconnect. So the simple answer to your question is dialogue. Once you get these insights, then it’s down to dialogue.

Phil | We say, ‘beliefs divide and values unite.’ Beliefs operate at this level up here—in the mind, but values operate much more on a heart and soul level. And when we can be in dialogue at a values level, we really start to discover what’s important to our hearts. We can connect to people. A real example of this would be in Latvia where there was big division of racial tension between the native Latvians and the Russians living in Latvia. And they brought together a Latvian teenagers and Russian teenagers to really talk about how they would reconnect. So the simple answer to your question is dialogue. Once you get these insights, then it’s down to dialogue.

Tor | A dialogue you can have with yourself as well, which is called reflection.

Kosmos | Do you feel the definitions of those values are the same?

Tor | If I go and talk to the Pope in Rome about respect, he will have certainly a definition of what that is. And if I go to the Hell’s Angels leader and talk about respect, I’m sure he will have a definition of what that is. It’s still respect, but values are contextual. And it’s combining with the world view that you’re living in as well. That’s why you have to have this dialogue that Phil is talking about, where you actually co-create and understand, if that makes sense.

Kosmos | It does make sense. In conflict resolution, the first order of business is to get people in a room and find out what they can agree on. We all want the best for our families. We all want to be safe and secure. So yes, we always want to start from the place where we have some agreement. But I think your point, Tor, is it’s really important that we can have very different interpretations of these values.

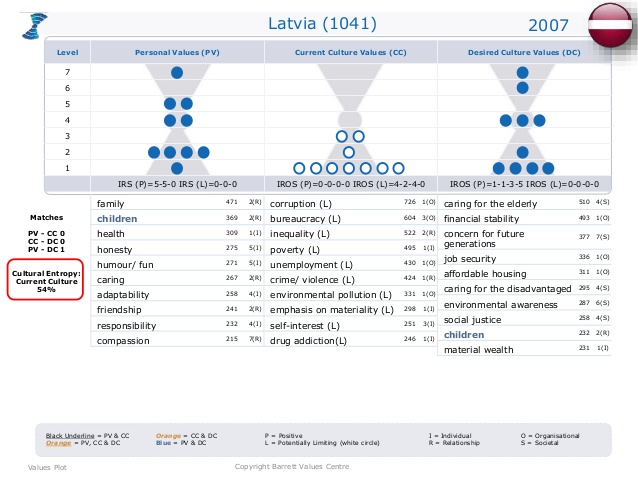

So looking at the example of Latvia in 2007—the first array of dots is the participant’s personal inventory, a personal assessment of ‘my’ values and what I care about. And then the second set of dots is my perception of the ‘other,’ the organization or community I am part of—in this case my perception of deficits in the cultural values of Latvia. And the third set shows the desired transformation, or integration that must take place through some process.

So looking at the example of Latvia in 2007—the first array of dots is the participant’s personal inventory, a personal assessment of ‘my’ values and what I care about. And then the second set of dots is my perception of the ‘other,’ the organization or community I am part of—in this case my perception of deficits in the cultural values of Latvia. And the third set shows the desired transformation, or integration that must take place through some process.

If we apply the model to humanity and nature, right now—we would see that humanity is saying, “I want more of something, because I’m fearful and distrustful.” But when we look at the values we aspire to, we might say cooperation, living within limits, honesty. There’s a disconnect.

Phil | Let me just pick on honesty for a second, because this list is a list of personal values. These are what people need in their lives. It doesn’t say this is what I’ve got fulfilled in my life. In fact, when something is fulfilled, it probably wouldn’t even show up on your list because you don’t think about it anymore. When the word honesty shows up, it says I’m still working on honesty for myself and in my relationships because I have not yet achieved that. So the fact that the word is honesty is there, it very rarely means that someone has achieved nirvana, the ultimate of honesty. It usually means this is really important to me, but I’m not there yet.

Kosmos | So, many activists experience a burnout experience. And we each have had some burnout at some point in our lives. How do we understand burnout from a values perspective? When I burn out, it’s like I just don’t care about the things that were so important to me, or if I do, I’m just so overwhelmed or disappointed that I want to give up.

Phil | You’ve actually just sparked me by looking at this through the lens of burnout.

That is the culture that people saw of the USA in 2011. Blame bureaucracy, waste of resources, corruption, materialistic, uncertainty about the future, conflict aggression, crime violence, unemployment short-term focus. There’s not a single positive value in that list. I would say at that stage the USA was in psychological burnout. But most people could leave their homes in the morning. They could go to the shop, they could go get a coffee, they could go to work. However, these things were all seen as aspects of society, because that’s the message the media was feeding them.

Tor | If I take myself as an example, I was 37 when I was diagnosed with diabetes. I didn’t think of health. I didn’t think of what I was eating, but that became a very important question for me. So it didn’t change my values about wanting to do or make a difference, but my focus was drawn down to my health naturally, because being healthy is a basic need we have as humans. When activists burnout, their basic needs are not being met.

Presently, we hear the call for common good, but we are drawn to meeting our basic needs because of the crisis. In order to move from that, we will need to develop more common good values, more uniting, and what we really all aspire to.

Kosmos | That is a very felt sense for me right now that on the one hand we seem to have a disintegration of values in the US—the values of truthfulness, civility. At the same time, we have seen an upswing in values of sharing, cooperation, working together, alleviating suffering.

You said something really important, Phil, and that is the picture that the media paints. We can all do this inventory of what our values are, and maybe we can be honest about that to the extent that we have self-awareness. But when we project onto the outer organization or the society, we bring a lot of baggage along with us. And it’s mediated by many things including our own trauma. That doesn’t diminish from the value of the model I don’t think, but has to be taken into account.

Tor | We did a national survey of Sweden. We saw a huge increase of words, like hate and crime during a time when we had this huge intake of refugees coming from Syria and Afghanistan. When we looked at the actual statistics about crime, the increase was 0.1%—negligible. So perception is everything as we say. It doesn’t mean that it’s wrong—people are going to act on perception, not statistics. And what the media is feeding is actually also creating that reality.

Phil | Just to add to that in both the UK and Sweden, we’ve done a values assessment where we ask, “how do you experience living in your community?” We see things like buying local and friendship, and there’s some problems like drug addiction within there. But generally it’s a very positive picture, but then you ask, “how do you perceive the nation?” And suddenly, it’s all negative.

What we’ve learned is that you can only experience what you can see and interact with through your physical senses. You don’t experience a whole nation. You perceive the nation through social media, the news, the television, and all those other things. The message that they send to you every day is the message that then becomes what the nation looks like.

Kosmos | So there’s a sense that, the closer we are to our body, beginning with our mind perhaps, the less distorted our perceptions. And then as we expand out, we have a more distorted view perhaps.

Phil | In a way. Because we can also have a very distorted view of what’s happening inside of our mind, depending on the degree of our consciousness, but there is an overlay. Consciousness enables us to say, “How big is the world that I’m part of?”

As soon as my world is big enough to encompass my village, it’s like, “Oh, these people are all me.” That’s why we see so many kids today who are very quickly coming to the consciousness that, “I’m a citizen of the planet.” Then they can’t drop litter on the streets anymore because that street is them. They completely identify that being is unitary with the planet. They can’t harm more.

Kosmos | So the intervention, if I understand the model correctly is a process of dialogue as a critical key for unlocking healing and integrating. I think that’s a good place to bring in the SDGs, because the SDGs ask us to look at our interconnection with the world and connect to a bigger vision of responsibility, stewardship, and interconnection. And if that can happen in a group, and then if those groups can then influence the society, maybe this is a key to the whole process somehow. That we unlock the ability for the individual to see themselves, to have the insight that they are part of the universe.

Tor | That is coming back to that fact that it all starts with the individuals being sustainable themselves. It’s me as an individual. So to create a sustainable world, we need to think about how can I become sustainable myself in who I am and how I regard myself and how I live my life and how I act in my life. That’s the starting point.

Kosmos | It is. Perfect. There is that energy of personal transformation and personal consciousness, and I think also we generate that collective energy when we can come together and reflect upon our connection.

Tor | We attract these different energies with each other. But if we are individuals who have energies based on fear, we will separate. If we have energies that are more based on love and care, so to speak, or togetherness, we will attract those individuals. That’s why we see different kind of movements. That’s why even the fear could attract it.

Kosmos | This is happening with QAnon. They do feel they are part of a family. So there’s these very positive values of connection and family on one hand, but it’s within a bubble that is quite dangerous and destructive.

Tor | Yeah. Yeah, exactly. So we need to have sustainable individuals that create sustainable organizations.

Kosmos | The new edition of Kosmos is called ‘Century of Awakening.’ Now, this is a pretty bold claim that we are in the midst of a century of awakening. Maybe we could spend the last part of our discussion just talking about what that would mean from the perspective of the Value Centre. What would a century of awakening look like and how could this model help us to achieve it?

Tor | Right now we are suffering from a worldview that doesn’t serve us. We are trying to transform to a new worldview. Richard Barrett has this world global consciousness index, where he is looking at nations and different type of world views in different parts of the world. It’s also called the wellness index. Some nations, I would say most nations today are operating energetically, like on level three. Then there are some who are energetically operating on level four, you could say.

Phil | I’ve got two quick, two examples of what we’re actually seeing and how this is working right now and how the model is helping. One is six weeks into the pandemic we launched a global values assessment to look at what was the impact in organizations of the pandemic. And the short version of the story is that in six weeks we saw a transformation that would typically take organizations five to seven years. And to characterize that, what we saw was a shift from the industrial age, which was all about hierarchy, control, and power to more of a human age. A people age that was more about caring, collaboration and agility.

So people can now work together and that’s what people are experiencing now. Adaptability, digital activity, teamwork agility, balance homework, cross-group collaboration, caring, amazing things. And what they also want for the future is largely what they’re already experiencing. It was, as I say, a tremendously fast transformation!

Kosmos | Is there some something here where these kinds of pressures or converging crises are in some way catalyzing us to make a significant shift in consciousness? Do you see that, or is that wishful thinking?

Phil | I would say yes. I believe that it is possible to go to a transformation process based on positive vision of the future. But I think 99% of transformation comes from the requirement to…or being plunged into crisis. You’ve got to figure it out something new.

Kosmos | Yet, certainly if I turn off the TV, I can walk outside my door and I’m in a literal paradise. The woods and everything—I don’t live in fear. (Maybe the coyote, but I’m not really afraid of him.) However, that experience could be completely different if I lived in North Philadelphia and I’m a single black mother worrying that my children may not make it home from school. A very, very different reality.

So, it falls to those of us not in deep crisis, who have the privilege and capacity to make this shift, to play a significant role. Not everyone has the capacity to receive a message of hope. They just don’t. They’re embroiled in what they’re in and hope to them rings completely false.

Tor | Something came into me. Nelson Mandela coming from where he was treated and the situation he was in, but he had that stillness and that life inside of him that helped him understand.

Kosmos | Yes, of course—and look at the Black Lives Matter movement.

Tor | Exactly. Sometimes we believe that the more fortunate must lead, but they can be even more suppressed and stressed, so to speak. I completely agree we need to work together to make this happen.

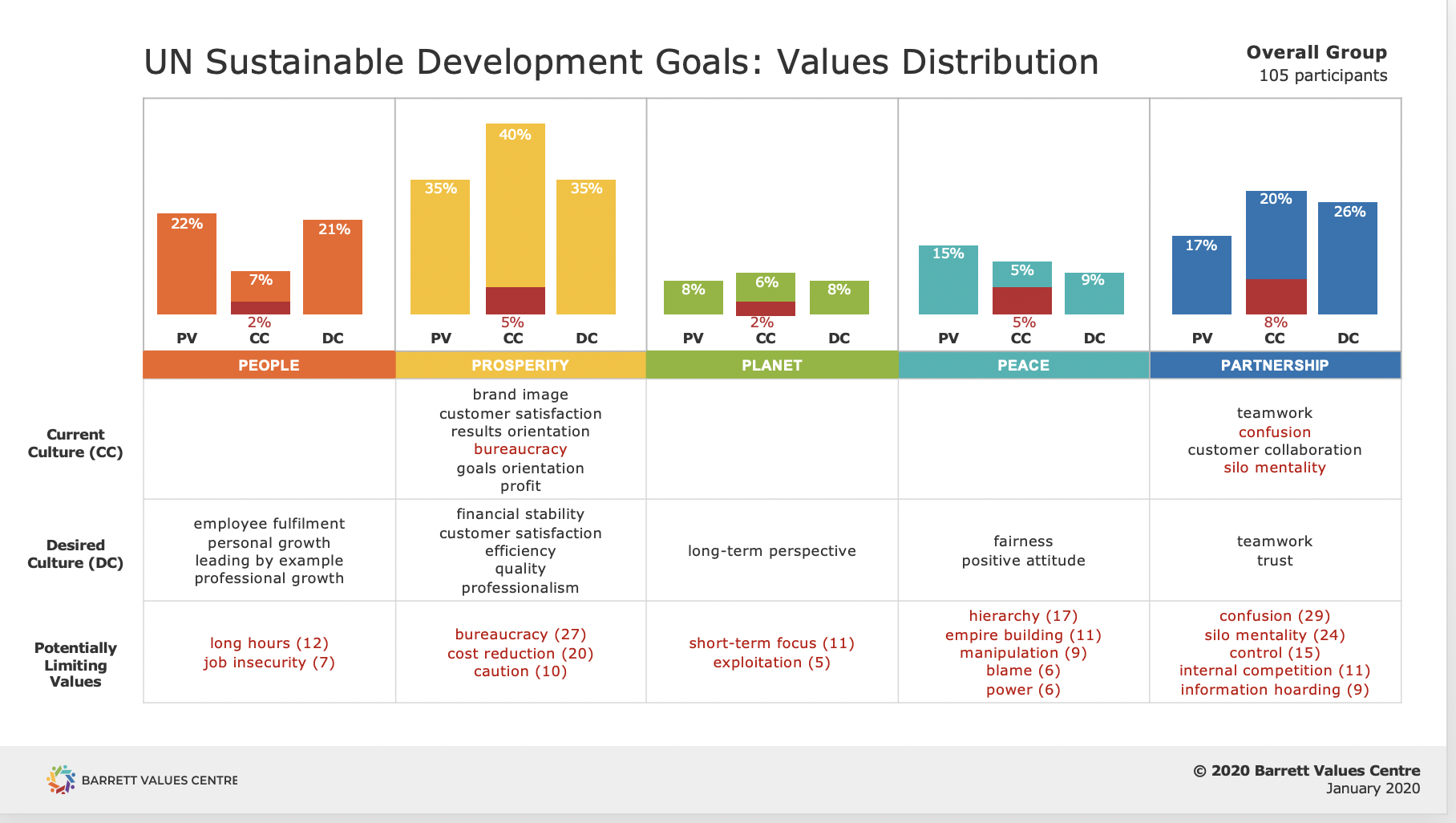

Phil | In the summer if 2019 we had a call from Wendy van Tol, a truly brilliant leader with a big heart, from PwC. She said that many of their clients are aligning their purpose with the UN Sustainable Development Goals but didn’t know how to align their culture. She asked two questions: How can organizations measure their cultural alignment, progress, contribution to the SDGs? Is it possible to find a values-based measure for SDGs? Her questions inspired Tor and I and sparked arguably the most important development process in BVC since the development of the original Barrett model. To apply the work directly to the biggest challenges facing humanity at this moment in history.

Using the UN 5Ps for Sustainable Development (People, Prosperity, Planet, Peace and Partnership), we have created a way to take the data from the Barrett values assessment and show both how sustainable the culture is and the actions needed to live and contribute to a more sustainable future for all. Jim Morrison said this very simply: “There can’t be any large-scale revolution until there’s a personal revolution, on an individual level. It’s got to happen inside first.” That applies to everyone but in this context, particularly to leaders, organizations and governments.

This report helps you to see your focus and gaps to identify your strengths and shortcomings to grow a sustainable culture.

Kosmos | Anything we put our attention on and make sacred, become sacred. Only we can make life sacred again. Only we can do that. So, this is so key to the Sustainable Development Goals—that we have a sacred responsibility to them. Thank you.