Medicine from the Margins

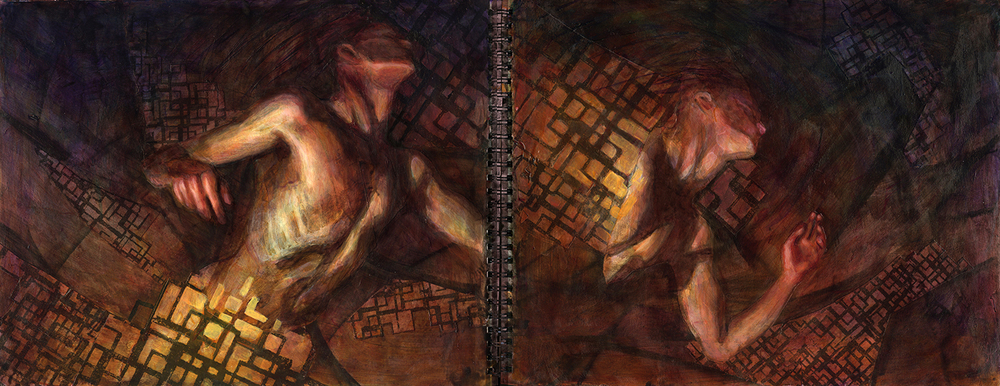

Featured image | detail from The Red Book, by Carl Jung

Marginality has always been a core value of depth psychology and Trickster mythologies. Dreams exist at the margins of our consciousness, directing our attention to marginal areas of the psyche that we would rather not see. Tricksters are gods of the road, travelers, edge walkers, and eccentric vagabonds who don’t quite fit in at the banquets atop Mount Olympus; nor do they find themselves at home around the village hearth (though they’ll happily help themselves to morsels from either table). We can always find Trickster at the borderlands of the village, of the cosmos, of the psyche itself. Or rather, that’s where Trickster finds us.

The Trickster Archetype Cross-Culturally

Trickster mythologies often teach us about the necessity for human culture to embrace and maintain a relationship with the marginal wilds of the natural world and the soul itself. In countless fairy tales, an ailing kingdom is revived by a heroine or hero taking a journey beyond its boundaries. The medicine needed most is almost always found in the dark forest, not in the comforting lights of home.

The Jungian concept of the anima/animus, which implies that different genders psychologically contain one another, subverts modern culture’s basic understanding of gender. Queer, trans, and nonbinary people may find a mythopoetic patron in Trickster, for across world mythologies, Trickster embodies the in-between spaces of gender and sexuality. While most often appearing in cultural narratives as male, Trickster frequently shifts into other bodies, sexualities, and genders. Loki transforms into a female horse, mates with a giant, and gives birth to Odin’s eight-legged steed, Sleipnir. Eshu often appears as both male and female, with multiple forms of genitalia. In stories from the Winnebago tribe, Coyote transforms into a woman at will.

In alchemical and Greek traditions, the union of Hermes and Aphrodite sublimates into a nonbinary being known as the Hermaphrodite. While now considered a stigmatizing term, its origins may speak to a mythic root of queer and trans identities. Trickster embodies and lives multiple identities at once. Changing and eschewing gender is an essential function of Trickster gods, who do so through a mythic drive to create something new and unexpected. Queerness, of course, isn’t something new but as old as the myths themselves.

Neurodivergence and conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are also marginal (and marginalized) states of functioning experienced by an increasing number of people. Many people, especially those with autism, receive messages from childhood telling them they are different, deficient, or somehow don’t fit in with the standards of neurotypical culture.

As they sit in the back of the classroom or in a quiet corner of a bar, neurodiverse people are also prone to novel ways of thinking and experiencing the world that do not conform with mainstream, neurotypical avenues of perception and cognition. Alan Turing, widely regarded as the progenitor of computer science, was both gay and likely autistic. He suffered immensely in his life because neither identity was welcome in the world around him. Many other geniuses, like Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Emily Dickinson, and Carl Jung, have all been characterized as eccentric, hyperfocused, antisocial, reclusive, or simply bizarre, and may have been autistic.

The gifts we’ve received from these groundbreaking thinkers are beyond measure. The role of neurodivergent people in culture at large is one of profound creativity and visionary ingenuity—precisely the role that Trickster figures play in myth.

Like their mythical counterparts, they don’t always “fit in” because their unique medicine derives precisely from their experience at the margins of the psyche and brain. One could even argue that neurodivergent people’s ability to think in novel and nonconforming ways puts them at the cutting edge of human evolution.

The margins of culture are almost always responsible for the greatest breakthroughs in art, philosophy, and spirituality. Black culture, marginalized and oppressed in American and European society for centuries, has birthed some of the most enduring art and music of the modern era.

On every level, medicine comes from the margins. From an ecological perspective, the borderlands between different climates and ecosystems harbor the greatest levels of biodiversity and therefore the greatest potential for fascinating adaptations.

The practice of permaculture values the margins as one of its central principles, understanding this archetypal truth echoed throughout ecologies.

Human culture gets into trouble when things gravitate too heavily toward anything mono, anything decidedly one-sided. Monocultural fields of wheat need to be doused in pesticides simply to survive. Monotheistic religions have clashed for centuries, often over forgotten reasons. Monotonous politicians drone on as they defend monopolistic corporations hoarding increasingly obscene amounts of wealth. Meanwhile, Trickster waits in the margins, flipping a coin, biding their time.

Vulnerable Uncertainty

Vulnerable uncertainty is a notion that I try, and often fail, to integrate into my daily life. Making space for the hat (or cloak) of many colors continually brings me to the edge of my comfort zone. Things might get a bit messy. And I have to trust that Trickster is teaching me through the mess. Vulnerable uncertainty is a cornerstone of my work as a therapist and psychedelic guide, and perhaps the most rewarding element of my intimate relationships. Every time I sit with a client about to undertake a psychedelic voyage, I feel myself returning to this vulnerable precipice of the known.

So now I wonder: what might it look like to bring this principle of vulnerable uncertainty and binary ambivalence into our broader relationships and communities? How might Trickster dance with us if we allow them more space in our daily lives, especially when we are rubbed the wrong way by someone’s viewpoint or opinion?

Somehow, I don’t think Trickster would approve of the vitriol and righteousness that is now the standard communication style in our internet age. I don’t claim any truth here, but let’s call it a hunch: we disrespect the gods when we dismiss each other. Instead, there’s a whisper in my ear pleading that we sit down at the table together under the bougainvillea blossoms, pour some mezcal, and talk long into the night.

Adapted from Psychedelics and the Soul by Simon Yugler, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2024 by Simon Yugler. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.