The Unintelligent Age

A prologue for habit

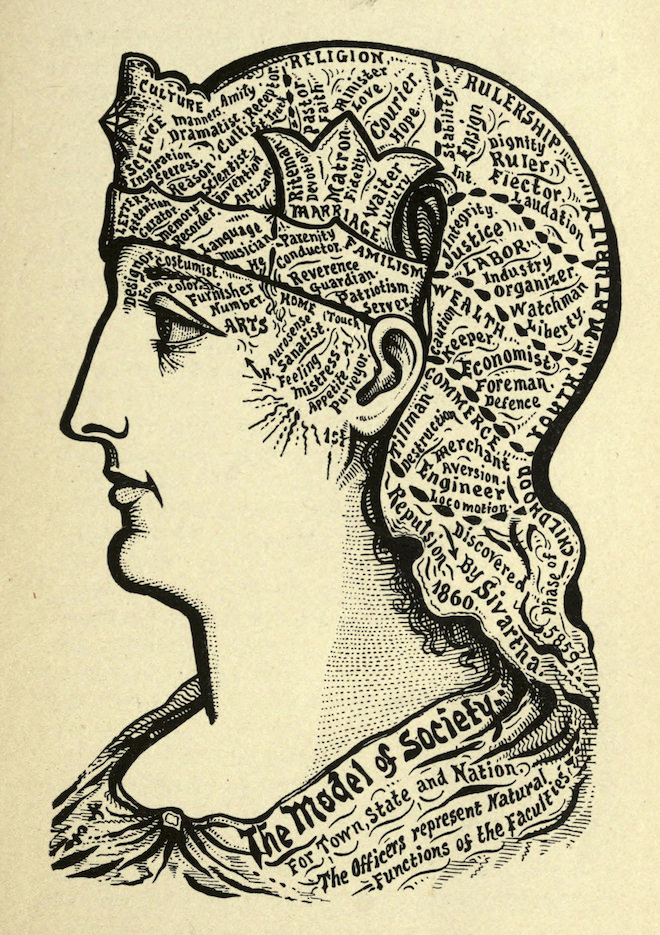

Have we become so dependent on rational, logical, analytical thinking that it now does us more harm than good? Might it be limiting, rather than broadening, the information we have and our potential? With these questions in mind, this essay is an invitation to pause, check your thinking, and train your brain to be ambidextrous. Whenever you find yourself justifying something, explaining something, or analysing something in your professional or personal life, please pause and check: Are you relying purely on logic and rational thinking? Are you relying on a set of assumptions about something you don’t understand firsthand? Are you relying on empirical evidence alone? If so, then with the pause you have taken, try considering the emotional point of view, the knowledge of first hand experience, and embrace new ideas with creativity and imagination. You might even use neuroscientist, Kris de Meyer’s, steps for becoming unstuck from what he calls our ‘social brain’.

The Unintelligent Age

The themes at the World Economic Forum (WEF) often set the agenda for many other conversations amongst the ‘global leaders’ of the world. This year, the WEF convened under the theme “Collaboration for the Intelligent Age”. It was my reflection after attending the WEF, that it might be more accurate to say we live in the “Unintelligent Age”. Our overreliance on the rational, on empirical data, and a modern euro-centric lens on how we think limits our potential. Only by freeing ourselves from this dependence might we become collectively intelligent as a species again. By rebalancing left-brain logic and rationalism with right-brain creativity and empathy. By being ambidextrous.

Roughly 6% of the global population are Indigenous Peoples. Not only that, Indigenous Peoples currently steward and protect around 80% of the planet’s remaining biodiversity. And yet, at the WEF where ‘Safeguarding the Planet’ was one of the five main topics, roughly 0.2% of the official attendees were Indigenous Peoples. Six people to be precise. Most of the 3,000+ attendees are paying members who pay tens of thousands of pounds for a WEF membership; an intelligently designed system destined for inclusive cooperation, wouldn’t you agree? (Please receive my tendency to sarcasm in jest only.)

I was fortunate to attend a session at the WEF Open Forum. (Not the official attendees forum but the one anyone in town can attend to join discussions not considered ‘important’ enough for the real WEF forum). The session was ‘Making the Case for Nature’. I won’t dwell on how sad it is to think that we even need to make the case for nature, because the discussion was brilliant in spite of that. The session included three of the Indigenous official attendees: Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim, President, Association for Fulani Women and Indigenous Peoples of Chad (AFPAT), who moderated the conversation, Mindahi Crescencio Bastida Munoz, Coordinator, Earth Elders, and Justin Langan, Curator, Winnipeg Hub.

It was during this session that I was struck by how unintelligent our age really is. Joyeeta Gupta, Professor, Environment and Development in the Global South, University of Amsterdam, compellingly spoke about how a rights-based approach could help nature. Rights like animal rights, could be applied to tree rights, ecosystem rights, and soil rights or human rights legal principles, like ‘Do No Significant Harm’, could apply to nature too. Because, she reflected, nature cannot speak so it needs the right for representation. Right at that moment Hindou interjected commenting how it is interesting to say that nature cannot talk for itself. Dominant thinking, perspectives and ontologies are so anchored now in logic, reason, law and empirical science, that we often don’t even realise the assumptions we make in how they speak. The unintelligent penny had dropped.

“Intellectually, rationally we think that nature cannot speak, yes. But nature is giving us lessons,” came the slow, intentional, precise voice of Mindahi, Coordinator of the Earth Elders and elder of the Otomi-Toltec Peoples of Mexico. “Nature is speaking. It is we who are not listening.” A sense of deep listening reverberated in Mindahi’s voice. I could not help but hear nature’s lessons in the tonality with which he spoke.

Stop, listen, and imagine

“If you look at Mother Earth as one body, Europe is the head of the body,” says Aunty Ivy, spiritual leader and founder of Our Foundation. For four hundred years societies have been dominated by post-Enlightenment European thinking (not least in the form of the English Language) that has overemphasised rational thinking, numerical performance, empirical data and extractive mindsets. We have become so obsessed with this way of seeing the world and making decisions, that we have become distracted from the rest of the information available. Rory Sutherland, Vice Chairman of Ogilvy and Behavioural Science practitioner, describes in his talk – “Are We Now Too Impatient to Be Intelligent?” – how in the present day, “we sometimes allow the urgent to drown out the important.” All of which, Rory reflects, is at least in part due to our dependence on data for rationalising and justifying decisions to others and to ourselves.

We have become so focused on the urgent then, that we haven’t the time to pause and listen to the lessons of nature. Instead, even in the case of climate change, we analyse and analyse, we gather more and more data on how bad the situation is, rather than creatively deploy, learn, adapt, and then re-deploy new ways of living in harmony with the planet. We have lost the perspective and humility to see ourselves as one very young species in the billion year timeline of life on earth. Through the arrogance of extraction, we have lost touch with collective humility. In the rush of rationalisation, we have lost touch with collective empathy. In the noise of abundant evidence, we have lost our ability to pause, listen, and reimagine.

Of course, the WEF’s framing of 2025 as ‘the intelligent’ age is in reference to the rapid proliferation of Artificial Intelligence. Technology that learns to make decisions based on data from the past. That learns from and communicates almost entirely through signs, mostly letters, pixels and numbers. As a technology, is the-left brain in principle. And yet, a significant proportion of human communication is non-verbal. Dr Mehrabian’s research goes as far as to identify only 7% of communication in words themselves. And this communication doesn’t even include the quiet wisdom of information that is learned when we listen to nature, as Mindahi pointed out. If we come to rely on so-called Artificial Intelligence’s narrow way of calculating and making decisions to the point where it governs society so much that it defines our ‘age’, we will likely only perpetuate our unintelligence. So, this article is an invitation to pause, check yourself, listen and engage empathy, creativity and imagination in decision-making, as well as a bit of data and logic.