The Insurgent Power of the Commons in the War Against the Imagination

Armed conflict is clearly a major problem in our time, but it is worth considering another serious war that may be provoking so many wars. I refer to the war against the imagination. This phrase comes from Beat poet Diane di Prima, who wrote:

the war that matters is the war against the imagination

all other wars are subsumed in it. …the war is the war for the human imagination

and no one can fight it but you/ & no one can fight it for youThe imagination is not only holy, it is precise

it is not only fierce, it is practical

men die everyday for the lack of it,

it is vast & elegant

“The ultimate famine,” di Prima warns, “is the starvation of the imagination.” [1]

When an artist-friend shared these lines with me, I realized how profoundly they speak to modern life. In respectable circles, there seems to be very little room for wide-open dreaming and experimentation, or for stepping off in new directions to explore the unknown. But the realm of the unknown is precisely where we really start to see and live.

In today’s world, there are certain presumptions that serious people aren’t supposed to question, such as the necessity of economic growth and capital accumulation, and the importance of strong consumer demand and expansive private property rights. The more of these we have, the better, we are told.

These dogmas have sucked all the air out of our public life and politics. This is one reason that I have come to see the commons as a precious patch of ground—an important staging area for thinking and living our way past the prevailing orthodoxies. The commons is a space from which an insurgency might be launched. Indeed, it is being launched—if you train your eyes to see it.

I believe the commons paradigm can help us develop a new social and cultural vision, and new strategies for practical change. Paradoxically enough, redirecting our attention away from conventional politics and policy may offer the most promising possibilities for developing a transformational vision.

We are surely reaching a point of diminishing returns within the existing system. Real change and regeneration require us to jump the tracks somehow. We need to start imagining different ways of being, doing, and knowing—and we need to invent new institutional structures to support such a paradigm shift.

Beyond the Tragedy of the Commons

Let me first clarify what I mean by the commons—a term that is greatly misunderstood and misused. For most people, the first thing that comes to mind when you mention the word commons is “tragedy”—as in the “tragedy of the commons.”

That idea was put into circulation by biologist Garrett Hardin in a now-famous essay published by the journal Science in 1968. Hardin asked us to imagine a pasture on which farmers could put as many sheep as they wanted. The result, he said, would inevitably be the over-exploitation of the pasture. No individual farmer would have a “rational” incentive to hold back, so the sheep would over-graze and ruin the pasture, resulting in the tragedy of the commons.

What a tenacious little smear this has been! Over the past two generations, economists and conservative ideologues have embraced the “tragedy parable” as a powerful way to denigrate the collective management of resources, especially by government. Hardin’s just-so story has also proved useful for celebrating private property rights and, by implication, free markets and government deregulation.

But Hardin had spun out a fantasy with no empirical basis. He did not describe any actual commons. He described an open-access regime—a free-for-all—in which there is no community, no rules for managing resources, no boundaries around them, no penalties for overuse or free-riding, etc. That is not a commons. A commons consists of a community plus a shared resource and a set of social agreements, practices, traditions, etc., for governing it.

The scenario Hardin described more accurately reflects market economics in which everyone is a disconnected individual defined by their “utility-maximizing rationality” and competitiveness, which makes you a sucker to restrain yourself. You might say that Hardin really described the tragedy of the market—“Grab what you want and forget about the mess you leave behind.”

The late Professor Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University powerfully rebutted the whole “tragedy of the commons” fable in her landmark 1990 book, Governing the Commons. In 2009, she won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work—the first woman to win this award. Ostrom and hundreds of scholars explained how countless communities around the world have self-organized to manage natural resources without over-exploiting them—all outside of the market and state power.

Why, then, are these systems generally ignored by economists? Because when you’re studying market transactions as the main event of life, anything that doesn’t involve cash and market exchange isn’t all that interesting.

And yet, commons are everywhere. They are the ancient heritage of the human species. The International Land Coalition has estimated that there are over 2.5 billion people in the world whose daily lives today depend upon forests, fisheries, farmland, irrigation water, and wild game managed as commons. It’s the default mode of provisioning through nature! Yet, to we moderns, commons remain mostly invisible—or misrepresented as ineffective and marginal. Doomed to failure.

The huge achievement of Ostrom and her academic colleagues was to provide scholarly validation for the commons as a system of governance and provisioning. Ostrom showed that cooperation is actually economically consequential, something that other contemporaries, most of them males, scoffed at.

A Movement of Commoners Arises

Meanwhile, outside of academia, over the past 20 years, a related story has developed on a parallel track. A self-replicating movement of commoners has been arising to build an empire of their own—an insurgent, diversified network based on the ideas of commoning. Yes, the commons is not so much a noun as a verb.

Commoning is the social process by which people come together, figure out the terms of their peer governance, learn how to devise fair systems, how to deal with rule-breakers, how build a cohesive culture, and so forth. Who are these commoners?

- Farmers, villagers, pastoralists, and fishers who use community systems to manage crops, pastures, irrigation water, trees, wild game, and fish.

- “Localists” who want to restore the self-determination of their communities through community land trusts (CLTs), community supported agriculture (CSA) farms, alternative currencies and time-banking systems, among other commons.

- Croatians fighting enclosures of their public spaces and coastal lands, and Greeks developing mutual aid systems to fight the neoliberal economic policies that have decimated that nation.

- A rich Francophone network of commoners and others in Spain, Italy, the U.K., and India.

- A new “municipalism” of urban commons arising in cities like Barcelona, Amsterdam, Seoul, and Bologna to establish commons-based Wi-Fi systems, public spaces, social projects, limits on development, and more.

- Indigenous peoples—arguably the oldest commoners—fighting to defend their ethnobotanical knowledge and biocultural practices.

- A vast network of digital commoners creating free and open-source software, building open-access publishing systems, and establishing “platform cooperatives” as alternatives to wikis, Uber and Airbnb, and makerspaces and Fab Labs.

Through some form of spontaneous convergence—or rising of a collective unconscious—these various groups are discovering the commons and using it as a lingua franca. While they all traffic in very different resources and in very different circumstances, most of them have a least one thing in common: a victimization by global markets and capital.

Enclosure and the War Against Imagination

This brings us to the word enclosure. It is a word that helps commoners fight the war against the imagination. Enclosure names the great harms that occur when the market/state system privatizes and encloses our common wealth. Enclosure happens when something managed by a social cohort or rooted in an ecosystem is redefined as a market commodity. It is ripped from its context, converted into private property, and sold. Its price becomes its value.

This is an act of radical dispossession—the kind that defined the English enclosure movement of the 17th and 18th centuries in which millions of commoners were evicted from their forests and pastures, and forced to migrate to cities and England’s dark satanic mills.

We are now in the midst of a second major enclosure movement. This time, it is using less violent but even more effective weapons of dispossession. These include intellectual property law, digital technologies, Big Data and algorithms, and, as needed, raw state coercion and market power. As in the past, the mission is to seize the common wealth for private profit-making.

What Is Our Global Commons

“Global commons is that which no one person or state may own or control and which is central to life. A Global Common contains an infinite potential with regard to the understanding and advancement of the biology and society of all life, and hence requires absolute protection.”

Here are some examples:

Enclosure happens when the Hunt brothers buy up vast tracts of groundwater in the Midwest, turning priceless repositories of life into speculative commodities to be sold to the highest bidders. Enclosure happens when biotech and pharmaceutical companies patent genetic information about plants and seeds, and medicines and diseases. One-fifth of the human genome is now owned by companies as patents. The German company BASF owns more than 6,000 patents derived from genetic sequences in 862 marine organisms. Enclosure happens when industrial agriculture converts a living landscape into a vast, quasi-dead vessel of soil to grow monoculture crops. It occurs when the traditional sharing and cultivating of seeds are criminalized—which is happening today. Enclosure happens in Africa and Asia, as sovereign investment funds and hedge funds collude with governments to buy land that has been used for generations by subsistence communities and indigenous tribes. It’s a huge land grab that displaces millions of people and triggers new migrations to urban shantytowns and future famines: the English enclosure movement revisited.

Amazingly, conventional politics and economics don’t have a name for the idea of enclosure. Instead, it’s usually called “innovation,” “wealth creation,” and “progress.” The language of the commons helps us debunk these modern-day fairy tales.

The Commons and Place-Based Stewardship

What does all of this talk of the commons have to do with rural America and farming, ecosystems, and human well-being?

I’d like to propose that the commons discourse can help us break out of the claustrophobic mindset of contemporary politics and economics, especially as they apply to rural America. The concepts and language of the commons—and scores of real-life projects—can open up new ways of thinking that go beyond the traditional “progress narratives” of growth and “development.”

As the era of climate change descends upon us—as we begin to recognize the fragility and costs of global supply chains for food, energy, and water; as we learn how giant corporations work with government to consolidate market power and squeeze out small players; as we discover how markets tend to flatten the distinctiveness of place and identity and propagate inequality and division—we learn what pre-moderns have known for millennia: place-based stewardship and community self-reliance can offer more ecologically rooted, humane, and satisfying ways to live.

But how can we possibly work for such a vision? One thing is for sure: it won’t come via Washington, D.C., or new trade policies or farm bills, at least not primarily. It will first require some deeper cultural and personal shifts from us—and the development of new sorts of commons-based institutions.

It will require that we wean ourselves away from a mindset that is transactional—which is the essence of capitalist markets and culture, and a mindset deeply embedded within each of us—and learn to embrace a mindset that, at its core, is relational, where we see ourselves as interconnected and interdependent, and can show our vulnerabilities as humans without being taken advantage of.

That’s where the commons helps to catalyze a transformation. The language and framing of the commons helps name this different order of life. Evolutionary sciences show that the hyper-individualistic story told by conventional economics is an utter fantasy. As E.O. Wilson and David Sloan Wilson (among others) have shown, we are a species that has evolved through cooperation.

We are not free-floating individuals without histories or social ties, untouched by geography or community. In reality, we are all nested-I’s—individuals nested within larger biological webs and within social collectives that profoundly shape us. Land and natural systems are not mere resources as the price-system implies. They are what I call care-wealth.

It’s this relationality that needs to be brought to the foreground. As Thomas Berry put it memorably: “The universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.” This is the ontological shift—the OntoShift—that we need to make as a culture and find ways to enact through projects and express through language.

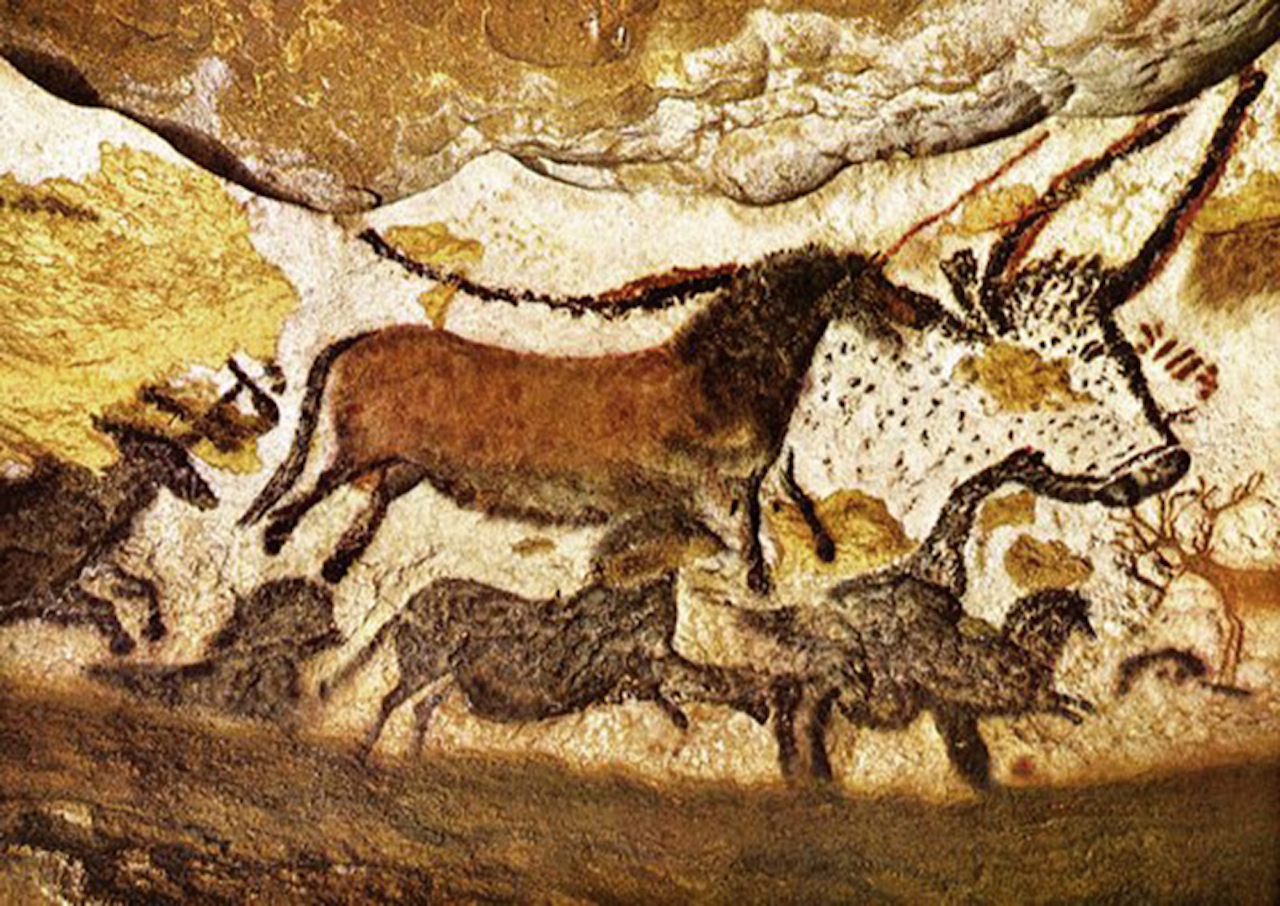

In a sense, that’s the purpose of the commons. It’s a rediscovered term that is being used to describe some ancient realities. It expresses the spiritual connections of indigenous peoples to the land and the cosmos. The commons is the land ethic that Aldo Leopold described. It echoes what Rachel Carson said about the subtle interconnectedness of all living things, and how Wendell Berry so beautifully regarded the human satisfactions of working with a landscape.

A commons is about having responsibilities and entitlements that flow from them; stepping up to long-term stewardship; making the rules of governance from the bottom up, with an accent on fairness, participation, and inclusiveness; and the inalienability of certain things. Some things just aren’t for sale.

In short, it’s all about relationality! It is here where a new vision for rural America needs to begin.

The standard wisdom is that farmers, agricultural suppliers, and rural businesses should double-down and try to compete more effectively in integrated global markets. They should get leaner and meaner and smarter, goes the pep talk. They should demand greater government subsidies and new forms of support. This is fair enough, so far as it goes.

But we’ve seen how this approach is fraught with problematic risks. Are we really prepared to accept permanent subordination to the corporate seed, biotech, and chemical giants? Do we really want to build a future based on volatile energy and food prices in an era of peak oil and climate change? Can we depend on dwindling supplies of water from elsewhere and owned by someone else, and on the shifting sands of international trade policies and tariffs?

The Commons and Rural Futures

A more constructive and secure long-term vision is for communities to become more locally autonomous and self-directed—to become less dependent on the global and national markets, many of which treat rural America as sites for neocolonial extraction in any case.

The more promising answers lie in greater relocalization and community self-reliance; in decommodifying our daily needs as possible; in working with the land and not abusing it; in sharing infrastructure and collaborations with other commoners; and in mutualizing the benefits that are generated.

This was roughly the strategy that civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer used 50 years ago when she and others purchased 680 acres of Mississippi Delta land and named them “Freedom Farms.” The goal was to provide access to land so that African-Americans could grow their own food cooperatively. “When you’ve got 400 quarts of greens and gumbo soup canned for the winter, nobody can push you around and tell you what to say or do,” she said. [2]

That is the beauty of commoning. It’s practical. You could say that it draws from the best of all political ideologies: conservatives like the tendency of commons to promote responsibility. Liberals are pleased with the focus on equality and basic social entitlement. Libertarians like the emphasis on individual initiative. And leftists like the idea of limiting the scope of the market. It’s all about cultivating a mindset of mutual support and building durable systems of relationality.

Following are some of these cooperative, benefit-sharing, relational approaches. Could one imagine an agricultural innovation more in sync with natural systems than the Land Institute Kernza grain? It absorbs more water than conventional wheat, prevents runoff and erosion, captures more carbon, and provides year-round habitat for wildlife, while, of course, providing a tasty food for us humans. Kernza has enormous potential to bring humans into a deeper, more regenerative relationship with the land itself, which will surely enhance the stability of agricultural towns.

Another commons-in-the-making is the Open Source Seed Initiative. Its basic purpose is to decommodify seeds to make them freely breedable and shareable, under terms set by commoners themselves. Currently, more than 400 varieties of seeds and 51 species have become, what I would call, “relationalized property”—legally shareable seeds that can participate in the gift-economy of nature and cannot be privatized.

Of course, land is another precious resource that has already been enclosed by capital or faces constant threats of enclosure. How can land be made more affordable and accessible, especially for young farmers, and be deployed as an object of stewardship, not simply ruthless market exploitation?

We know that community land trusts (CLT) are a powerful vehicle for land reform. They are a way for communities to take land off the speculative market and use it for long-term community purposes, such as workforce housing, town improvements, sustainable agriculture, and recreation.

Again: the strategy of decommodify and share. A CLT is a kind of commons because it socializes and collectivizes economic rent, and then invests it back into the community that helps create it. It’s a social organism for regenerating value, through democratic governance and open membership in its classic form.

Recently, the Schumacher Center has been developing community-supported industry—an offshoot of community-supported agriculture (CSA). The idea is to use CLT structures in novel ways to help decommodify land and buildings in a town. They can then be used for all sorts of “import-replacement” enterprises—production, retail, food—that recirculates dollars within the region.

FaithLands is another burgeoning land repurposing movement. It’s a small but growing movement of churches, monasteries, and other religious bodies that offer up their land for community-minded agriculture, ecological restoration, and social justice projects. It turns out that religious organizations own a lot of tax-free land, so they can potentially act like conservation organizations or land trusts.

A farmer working on church land said, “Our scripture starts with Genesis in the garden and ends with Revelation in a garden in the city—with Jesus in the middle inviting us to a meal. If we’re seeking to transform our food system in a way that’s going to be beneficial not only for ourselves, but for our great grandchildren, how can the church put [its] land into service?”

Simply asking, “What does the land want?” and “How can we feed the hungry?” lets us consider the radical idea of food itself as a commons. Why shouldn’t food be recognized as a basic human need available to all, and not merely as a private, transnational commodity? A famous essay published in 1988 called for returning a vast portion of the Great Plains to native prairie as a “Buffalo Commons.” That never happened, of course, but it did provoke valuable debates that have sparked some actual projects that move in this direction. A dialogue about food commons could have similar effects.

If a larger Commons Sector is to arise and flourish, however, we need more than small-scale, one-off projects. We need larger shared infrastructure to take things to the next level. This would open up new opportunities for commoning while thwarting the possibility of business monopolies and proprietary lock-ins, as we see in seed patents, exclusive supply chains, and the like.

The Three River Farmers Alliance—a supply infrastructure created by farmers in the area north of Boston, along the seacoast of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine—has brought together a variety of local producers to aggregate and distribute their foods. The shared distribution system helps them escape a dependency on powerful middlemen and build new bonds of trust among themselves. An open-source farm management software platform lets each farm function independently while also letting each opt-in to share knowledge and cooperate with others. This works only because there are shared data protocols managed as a commons.

The Fresno Commons in Fresno, California, is reinventing the whole farm-to-table supply chain under the control of a series of community trusts. This helps farmers, distributors, retailers, and others mutualize risks and benefits throughout the value-chain. The “profit” doesn’t get siphoned off to investors, but is used to improve wages and working conditions, grow food without pesticides, and make food more affordable to low-income people.

These stories point to the critical role that digital network technologies play in bringing gig-economy efficiencies down to the local level. But this is not just about market efficiencies and automated administration; it’s about building tech-based affordances for new forms of cooperation in today’s world.

Another such platform—cosmo-local production—is an emerging production process in which knowledge and design are co-developed and shared with collaborators around the world via the Internet. Then, the heavy, physical tasks of production are done locally, in open-source ways—which is to say, in ways that are inexpensive, modular, locally sourceable, and protected from enclosure. This is the idea behind Farm Hack, a global community of open-source designers of all sorts of farm equipment.

Cosmo-local production is also being used to design electronics (Arduino), video animations (Blender Institute), cars (Wikispeed), houses (Wikihouse), and furniture (Open Desk). The same general logic of global collaboration can be seen in the System for Rice Intensification—a global collaboration in which thousands of farmers around the world share their own agronomy innovations with each other, open-source style. It has improved rice yields four- and five-times over without chemicals or GMOs.

Consider also innovations in local government. There have been ingenious uses of government procurement to help strengthen the local economy, such as the pioneering work led by the Democracy Collaborative in Cleveland and, more recently, in Preston, England. In Italy, dozens of cities are developing “public/commons partnerships,” also known as “co-city protocols.” These are systems through which city bureaucracies collaborate with neighborhoods and citizen groups, empowering people to meet their own needs more directly and on their own terms.

Lest there’s any impression that the commons amounts to a bunch of white papers and policy ideas, let me underscore that the commons is about providing convivial spaces for us as whole human beings. A commons can only work by drawing upon our inner lives, sense of purpose, and cultural and spiritual values. It is, therefore, imperative that artists and cultural organizations play a conspicuous role. They express insights and feelings that our hypercognitive minds cannot. They express embodied ways of knowing.

I think you can begin to connect the many dots. No single one of them is the answer, but together, they help us to begin to think like a commoner. That’s liberating. That opens up new vistas of possibility. It helps us fight the war against the imagination and gives us hope.

In the 1980s, British Prime Minister Thatcher defended the harsh neoliberal agenda of privatization, deregulation, and fiscal austerity with a line that was often shortened to its acronym, TINA: “There Is No Alternative!” she would thunder. In truth, as I hope I’ve shown, the more accurate acronym is TAPAS: “There Are Plenty of Alternatives!”

But these alternatives are only available to us if we learn how to develop a new mindset, cultivate a new language to express our shared vision, and embark upon the hard work of building it out through commoning, project by project. That is our challenge in the years ahead.

This essay is adapted from a talk that David Bollier gave at the 2018 Prairie Festival, hosted by The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas.

References

1. Di Prima, Diane. “Rant.” The Beat Book: Writings from the Beat Generation, by Anne Waldman, Shambhala, 2007, pp. 139–142.

2. Penniman, L. and Washington, K.. Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018.

I have just completed an essay for this site, which is based on a similar concept to what is described by David Bollier. It does not describe common lands, although these natural resources are the main topic.

My essay was intended to not exceed the limiting 1000 words, which David’s essay obviously does. So I am sending this essay which is slightly longer than your limit, but which after much cutting and editing cannot be further reduced in length.

In spite of my efforts to become a member of this group of seekers after truth, no acceptance of my password change has been returned. Please return to me any additional requirements your editorial team may wish to make about these matters.