Restoring the Housatonic River Walk

How many downtowns have a native habitat component, buzzing with pollinators and the soothing voice of a river? A few may come to mind, but how many have been restored to an indigenous ecosystem without a single drop of herbicide or fertilizer, while also maintaining their place in human history, both industrial and social, all the while receiving over 12,000 visits per year? The Great Barrington Housatonic River Walk is a feat of vision and restoration. Where there was once an impenetrable tangle of bittersweet atop centuries of debris and neglect, forming a wall between life in Great Barrington and the River that runs through it, nearly 200 species of native plants now thrive alongside an accessible walking trail. The ongoing creation of River Walk also speaks to the human element. It marks the confluence of ecological renewal, environmental and social justice, the underpinnings of the industrial revolution, and the vitality of a downtown. Few, if any, ecological restoration projects can say the same. River Walk is a prototype for awareness on many levels.

The River Walk Ecosystem

In order to understand the ecological processes that are alive and well at River Walk, and what makes this piece of the Berkshires remarkable, we will start with the question: what is an ecosystem? Ecosystems are communities of species interacting with the physical components of a distinct area. Nutrients cycle through the animal, plant, fungal, microbial, and non-living features of an ecosystem. “Ecological processes” are the pathways by which energy flows between these “trophic levels”—the levels of the food chain.

An ecosystem can be large or small. For example, we can broadly describe the ecosystem of the forests of western Massachusetts. Or we can differentiate between the suite of species along ridgelines, those inhabiting floodplains, and the various communities in between. To illustrate further, the ecosystem of a particular pond is different from that of the stream that feeds it, which itself is ecologically distinct from the surrounding forest; and yet, these ecosystems are linked and interdependent.

River Walk is a “riparian” (riverside) ecosystem, delineated by its physical boundaries: the paved, human footprint along one side, and the Housatonic River on the other. River Walk, in its current restored state, cycles energy and nutrients through a thriving community of native woody and herbaceous plants. Like any ecosystem, it receives input from the sun, as well as the river, precipitation, and the animals that move through. Inorganic elements are taken up by the living layer and assimilated into organic molecules. Eventually they return to the soil and water in inorganic forms, available for another round through the biota.

From Neglected to Vibrant

Before settlement of the Town of Great Barrington, what is now River Walk was a floodplain, absorbing the River’s changing water levels and movements. Today, much of River Walk exists on artificial fill, debris deposited by townsfolk over the course of hundreds of years, well before River Walk’s creation. The fill expanded the town’s buildable downtown area but left the River without the room it needs to expand and contract naturally. This constrained path accelerates the River’s flow speed and increases the bank’s vulnerability to scouring. River Walk depends on experts who are skilled in shoring up the banks organically, using fibrous “logs” and native vegetation. In this way, River Walk pushes the concept of “ecosystem” into a new realm: its restored, native riparian habitat depends on bioengineering.

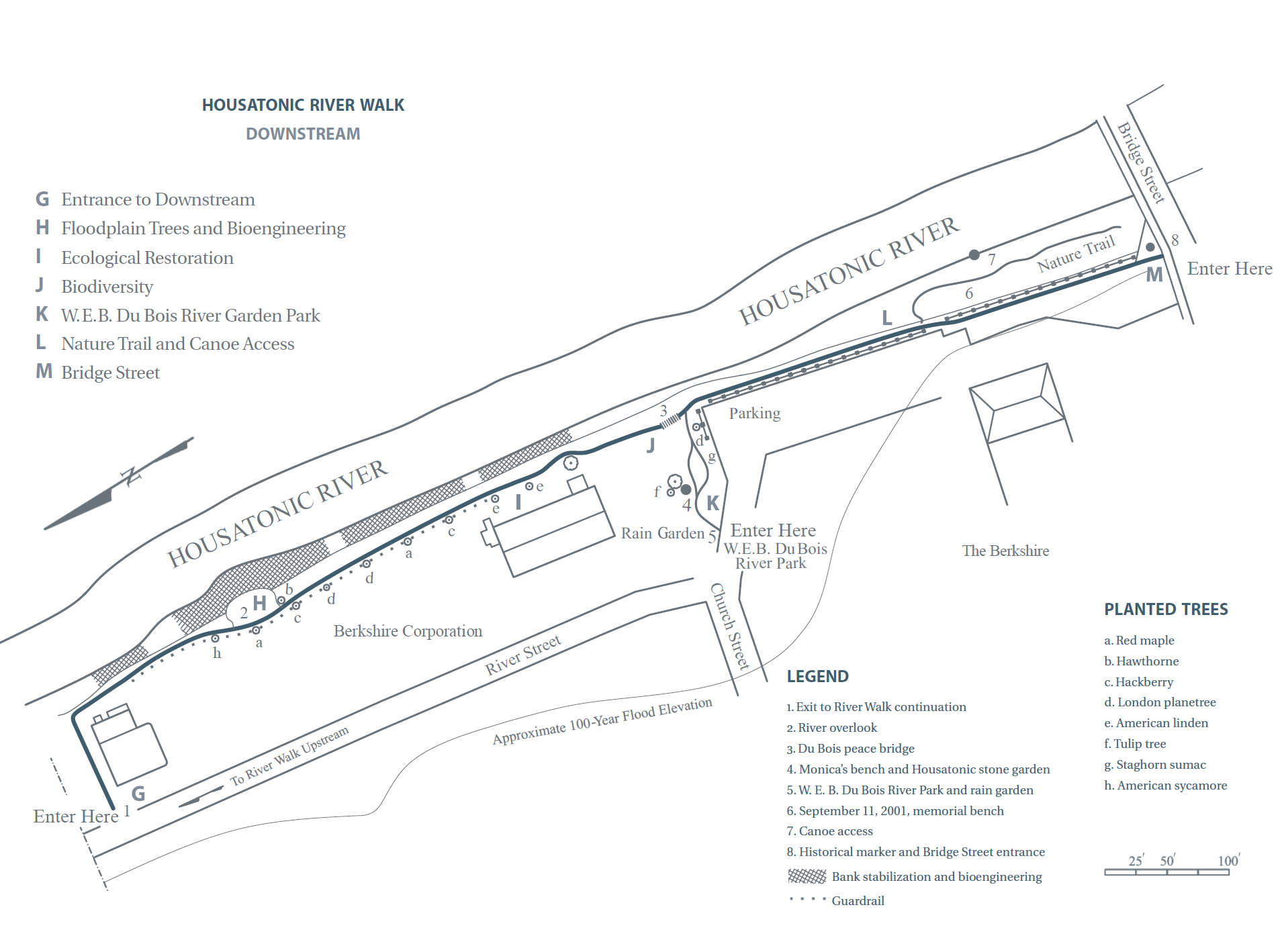

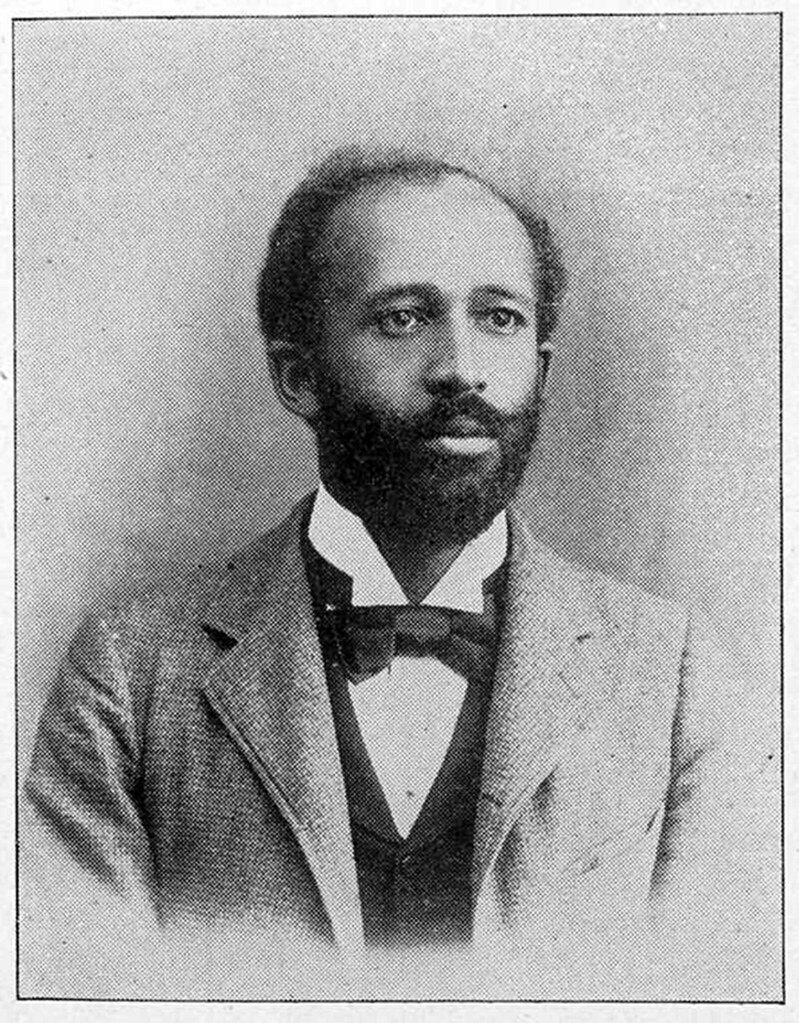

Once the Town of Great Barrington was established, the banks of the Housatonic continued to receive debris. As W.E.B. Du Bois famously said at a local meeting in 1930, the Town had “turned its back upon the River.” Thirty years later, Du Bois wrote: “the town had made a sewer of the beautiful Housatonic River, instead of the park it might have been.”

In 1988, although the wall of bittersweet obscured the River, and the riverbank was unrecognizable as a resource, 16 volunteers took the leap of faith. They began by removing 15 tons of garbage and demolition rubble. They unearthed an array of items: plumbing parts, tractor tires, and roofing materials, to name a few. The following year, 70 local eighth graders, their school adjacent to the River, continued this extraordinary feat. By 1990, the number of volunteers had grown into an army of 109 gloved and determined townsfolk. They removed another 82 tons of debris and garbage, mostly consisting of the torched remains of Melvin’s Prescription Pharmacy, which had been pushed over the bank after burning down in 1978. Similar efforts continued, year after year, and annually to this day.

“Rescue the Housatonic and clean it as we have never in all the years thought before of cleaning it…” Du Bois said in 1930. It took a while, but today, the cumulative number of volunteers for River Walk exceeds 3,100, and the removed debris totals over 400 tons. Neighbors no longer live adjacent to a “sewer.” Now, thousands of townsfolk and visitors have a view of the River and easy access to a walking trail through native habitat.

Life downstream from Great Barrington has improved as well. River Walk has transformed the way runoff is delivered to the River. Rain and snowmelt once ran directly into the Housatonic, picking up road salt, rubber and metal deposits from tire wear, dust and sand, antifreeze and engine oil, pesticides and fertilizers, and litter. Now the runoff has a chance to stop and rest, allowing the sediment to settle and the oil to separate out. The walking trail is composed of a permeable mix of gravel and soil stabilizers. Drop inlets, a rain garden, increased permeability of the soils, flow forms, and a healthy vegetative layer have restored the rapport between the town and the River that gave rise to it. Every ecosystem and town downstream receives fewer pollutants as a result.

Benchmarks of Ecological Health

Benchmarks of Ecological Health

Like the transformation of the quality of water entering the River, species richness and diversity indices have changed dramatically since the creation of River Walk. A handful of invasive species—Japanese bittersweet, knotweed, garlic mustard—once dominated River Walk, outcompeting native herbaceous plants and adversely impacting existing trees and shrubs. Now, over 170 native herbaceous and woody plants are established at River Walk. The success of new plantings is no longer a struggle against impoverished soils and encroaching invasive plants, as it was for the first decades of River Walk’s creation.

Ecosystems often are evaluated by their “connectivity.” Any parcel of habitat is more ecologically valuable if it connects to other habitats, or to larger tracts of intact upland or wetland. Before River Walk, downtown Great Barrington fragmented the riparian habitats to the north and south. Today, River Walk provides a steppingstone between those habitats. Seventy-five species of birds have been observed at River Walk—a clear indication of its success as a stopover for foraging, nesting, or finding shelter.

Linking the large natural areas to the north and south can have a synergistic effect. Habitat connectivity gives rare species of the Housatonic a greater chance of remaining viable and maybe even increasing their populations. Species such as the Creeper Mussel and the Wood Turtle can move from one area to another and interbreed, increasing the likelihood that the gene pool remains robust and resilient.

By acting as a steppingstone where there was once a missing link, River Walk’s contribution to the Housatonic ecosystem is many times greater than its footprint. Imagine a Luna Moth, or a Little Brown Bat, or a Cedar Waxwing moving along the river corridor. Envision the difference it makes to find a contiguous stretch of perch sites, nectar, native berries, and prey. Now try to imagine the turtle’s perspective. Consider how a paved-over human imprint impedes migration and dispersal for non-airborne critters. Indeed, Snapping Turtles have nested successfully in River Walk’s now fertile soil, ensuring connectivity across time, between generations.

Human Ecology

River Walk is unlike other riparian ecosystems in many ways. In order to convey a complete and accurate picture of its interrelationships and energy cycling, we need to look beyond textbook ecological processes and include the human element. Educators, historical figures, removers of debris and invasive plants, installers of riverbank reinforcement, cultivators of native plants, and many others are all vital to River Walk’s energy flow. River Walk exists thanks to human feats of native planting, bioengineering, clean-up, persistence, and vision.

Then and Now: Images of the Housatonic River Walk

At River Walk, pollination extends beyond insects and birds. River Walk was founded by the seeding of ideas across time—by the words of W.E.B. Du Bois in 1930 landing with River Walk founder Rachel Fletcher, some 60 years later. As River Walk’s students, interns, and fleets of volunteers disperse into new fields and jobs, their ecological know-how travels with them and seeds ideas in other communities. Think of milkweed seeds riding the wind currents.

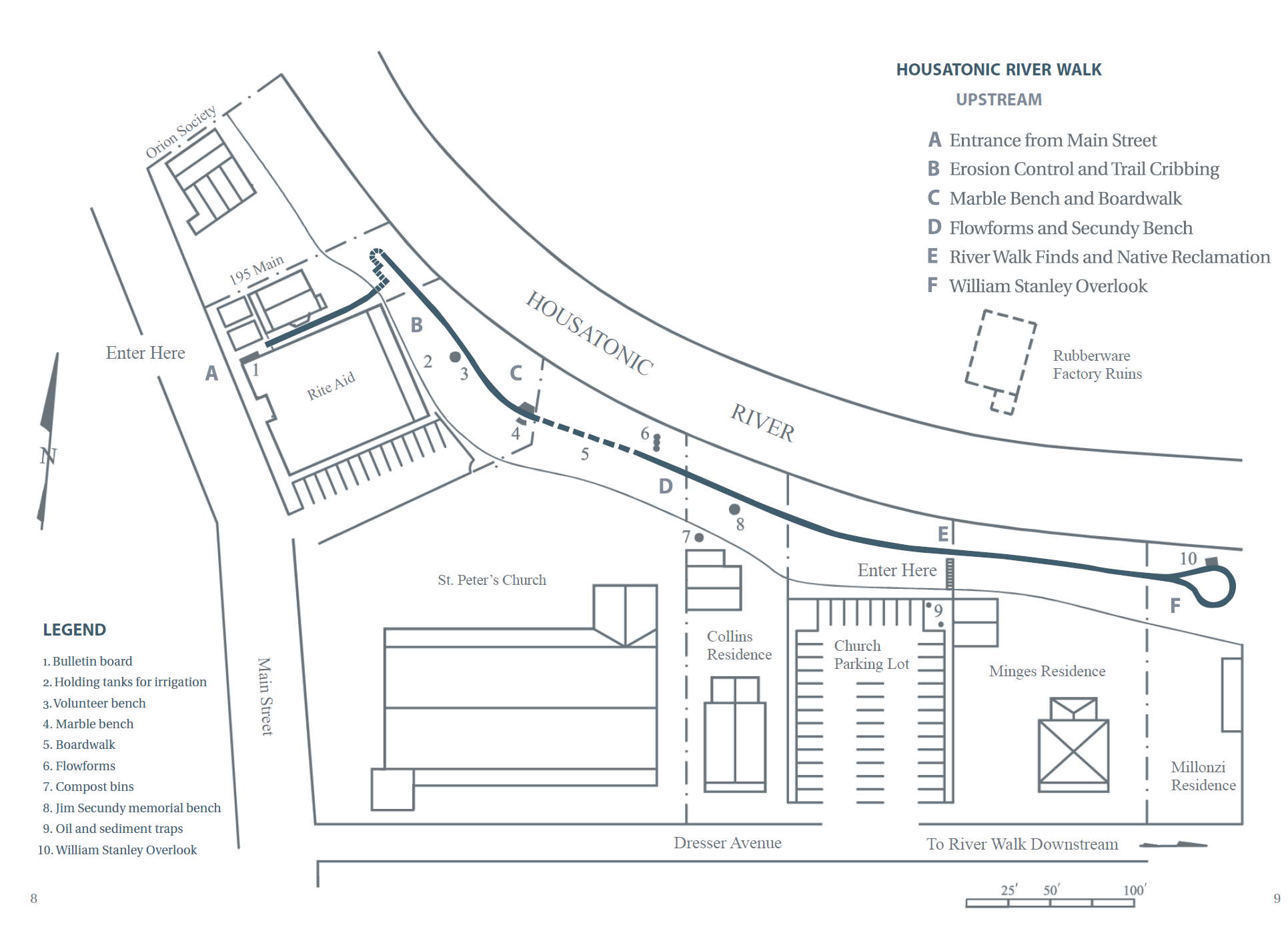

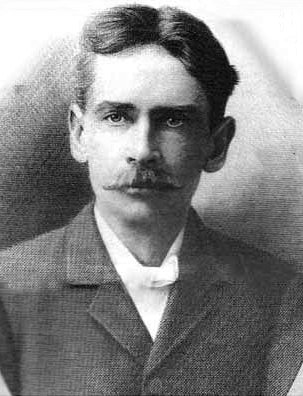

Cross-pollination at River Walk includes a relationship to human innovation and industrial history. One section of trail celebrates William Stanley, a founding father of the modern electrical age, whose experimental laboratory stood across the River. Stanley’s innovations, powered by the flow of the Housatonic, advanced electricity as we know it. However, the PCBs that would come to insulate his alternating-current transformers contaminated the River. River Walk incorporates this ironic confluence, so that visitors are reminded of our impact on the planet and the need for stewardship. Further, River Walk provides a laboratory for current issues of sustainability, where we can measure the success of eradicating invasive plants without chemicals, or monitor the recovery of depleted soils, among many other opportunities.

Cross-pollination at River Walk includes a relationship to human innovation and industrial history. One section of trail celebrates William Stanley, a founding father of the modern electrical age, whose experimental laboratory stood across the River. Stanley’s innovations, powered by the flow of the Housatonic, advanced electricity as we know it. However, the PCBs that would come to insulate his alternating-current transformers contaminated the River. River Walk incorporates this ironic confluence, so that visitors are reminded of our impact on the planet and the need for stewardship. Further, River Walk provides a laboratory for current issues of sustainability, where we can measure the success of eradicating invasive plants without chemicals, or monitor the recovery of depleted soils, among many other opportunities.

River Walk expands our definitions of species richness and diversity to incorporate the human element and the span of generations. A memorial to W.E.B. Du Bois, engineer of the civil rights movement on a national and global scale, rests adjacent to a memorial to Monica Schultz Fadding, local architect of the planting and propagation schemes that brought the riverbank back to life.

River Walk expands our definitions of species richness and diversity to incorporate the human element and the span of generations. A memorial to W.E.B. Du Bois, engineer of the civil rights movement on a national and global scale, rests adjacent to a memorial to Monica Schultz Fadding, local architect of the planting and propagation schemes that brought the riverbank back to life.

River Walk pushes the concept of habitat connectivity into a new realm, uniting ecological concepts with urban planning know-how. Great Barrington’s Main Street is roughly parallel to River Walk, and a mere 800 feet away at the farthest point. In minutes, we can walk from sidewalks and storefronts to the solace of a river and its living bank. We can cycle back through downtown, and do it over again, like minerals traveling through the biota of an ecosystem, our souls nourished by the flow.

As you course through, stop to take in a layer or two, the buzz of insects on native plants, the settling turbulence in the rain garden, the mindset of inventors and visionaries past, or the comfort of a turtle nest buried in the soft bank.

…a Conversation with Rachel Fletcher and Christine Ward

Rachel Fletcher is River Walk’s founding Director. She led the project for 30 years before retiring in 2018.

Christine Ward is the current Director. She also serves as a board member for the Great Barrington Land Conservancy, which has partnered with River Walk in the past.

Kosmos | Rachel, can you give us a brief history of the Housatonic River Walk? How did it come to be, and how have you been involved in the project?

Rachel | River Walk began in 1988 with a small backyard clean-up behind the offices of a local land trust, where remains of a burned-out building had been pushed over the Housatonic Riverbank in the center of town. Over the next 30 years, the original crew of 16 volunteers grew to more than 3000. In exchange for more clean-ups, eight different properties granted permanent public access and permission to build a half-mile of hand-crafted trail.

Over time, people from all walks of life transformed the once devastated stretch of riverbank into a natural, healthy ecosystem. Together, they made a place where the remarkable stories of W.E.B. Du Bois, William Stanley, and others could be told. River Walk became a National Recreational Trail, a site on the region’s African American Heritage Trail, an outdoor classroom, a laboratory for assessing best practices, and a local treasure.

Thirty years may seem like a long time to build a trail, but we have learned that the complete and sustained transformation of a site such as ours takes time and requires persistent, but discrete intervention, rather than massive quick fixes. Like slow food and slow money, the slow place-making that occurs at River Walk ensures our improvements will last. That the work requires many hands guarantees the community’s enduring involvement.

I recently retired from River Walk, having kept the ball in play as its founding director for 30 years.

Kosmos | In regards to the general population of Great Barrington, can you explain how aware the community is of this project and the important role it plays in their daily lives?

Rachel | In the early days, on almost any Saturday, dozens of community volunteers could be seen hauling rubble from the bank or hauling in stone to build the trail. A visitor walking the trail could look a few feet ahead and appreciate the remarkable transformation taking place on the next new section. We strove to bring everyone to the bank, if only to pick up a single piece of trash, so the River would never be trashed again. We don’t turn our backs on the River anymore.

The massive work of trail building is largely complete, and the riverbank’s natural habitat is coming into its own, with guidance from landscape gardener Heather Cupo. River Walk’s new director, Christine Ward, is reconnecting the public with the natural world through dozens of educational programs and activities for families. River Walk remains a laboratory for testing new biotechniques in habitat reclamation and riverbank stabilization. We look for ways to deliver clean water to the River whenever we can. The volunteer workdays continue, but the trail’s daily maintenance is largely in the hands of Greenager interns. Mentored by Elia Del Molino, they are learning the skills they need to be our stewards of the future.

Kosmos | It was mentioned in Suzie’s essay that over 3,000 volunteers have assisted with the River Walk over the years. Do you have any ideas as to what motivators have played a part in calling the community to action?

Rachel | The most significant motivator is the call of the River itself. Besides that, River Walk offers all of us the chance to envision and shape what we want our River and its banks to be. Everything is designed to be built and accomplished by hand, using noninvasive, labor-intensive methods, so that young people and citizens from all walks of life can be a part of its making.

Kosmos | The essay also outlines the negative impacts of human activity on the River’s ecosystems. To others who are interested in starting similar projects in their own localities, what wisdom can you offer to assist them in their journeys?

Rachel | Human interaction with the natural world doesn’t have to be adversarial. We can learn to be aware of our actions, modify our habits, and seek ways to remedy the impacts of unconscious behavior. We can and we must.

Preservation often aims to protect a natural resource by removing it from human contact. River Walk takes the opposite approach. By reconnecting people to the Housatonic River and reclaiming a discarded natural resource, once abandoned to industry, we instill a new ecological ethic.

Rivers the world over invite us to appreciate their profound historic and existential meaning. They are places of wildlife habitat, native flora, vistas and views, avenues of transport, geological formation, wetland and floodplain ecology, historic and prehistoric patterns of human settlement, and local legend. Thirty years of ground truthing at River Walk have taught us that humans can learn to interact beneficially with the natural world, as we:

- focus on discarded riverfront spaces, once the heart and soul of our cities and towns, while leaving nature’s untouched places to remain forever wild

- create riverfront experiences uniquely our own

- engage the community in determining the River’s fate

- design riverfront trails with the health of the River as our first priority

- provide meaningful interactions between people and natural places

- develop new criteria for town planning with a nod to history, ecology, and healthy human encounters.

Kosmos | Lastly, what does the future look like for the Housatonic River Walk?

Christine | The work at River Walk is ongoing. Our now-thriving native habitat depends upon maintaining the continued effort needed to beat back invasive species challenging many sections of the River, and to continue to foster the conditions needed by our native flora. Our trail is a vehicle for community members and students to explore our many connections to the River and to join in its care and advocacy. Our work, as always, keeps the River’s health to heart and requires a dedicated community in order to be sustained.

Kosmos | Are there plans for expansion or other projects in the area?

Christine | Yes, River Walk is the premier project of Great Barrington Land Conservancy, and now, inspired and informed by this success, the Land Conservancy is moving ahead to bring a new trail that will connect to River Walk—The Riverfront Trail. The initial stages of construction of this new trail will begin this fall. This new trail will connect visitors to a long-inaccessible section of the Housatonic River. The route will bring hikers near important wildlife habitat, dramatic river and birdlife viewing areas, wetlands, and through historic agricultural and urban landmarks.

References

W.E.B. Du Bois is quoted in Berkshire Courier, July 31, 1990, and a letter to George P. Fitzpatrick, 1961, courtesy of the family of the late George P. Fitzpatrick.