The Habits of Schooling

I remember sitting in the library one night early in my graduate school career. I was writing my first 20-page seminar paper on a subject with which I was wholly unfamiliar (Hellenistic painting). I had questions: about the topic, about the assignment itself, about the source material. But I was afraid. One part of me was urging the other part of me to get up, go to the professor, and seek clarity. The more fearful side of myself was anxious about being judged a fraud for being accepted to grad school at all; apprehensive of being yelled at or belittled; afraid to appear anything less than being in complete control.

My inner cheerleader was scathing. “What’s the worst that can happen? What has made you so afraid? Her job is to help you in situations just like this. You are in graduate school to seek the mentorship of these professors. What is wrong with you?!!”

I had to agree; what was wrong with me?

This internal questioning was new to me. Through all my previous years of schooling, a more timid voice controlled my inner landscape. That voice kept me on the straight-and-narrow path of good grades, high test scores, raising my hand, answering when called upon, and trying to remain unseen while getting by with minimal effort. Learning, if it happened at all, was merely a by-product. Even in my undergraduate years, I avoided any interaction with professors, took classes that I felt I could easily pass, did the bare minimum, and graduated with a degree in Ancient Greek at the expected pace of four years with precisely the number of credits I needed to emancipate myself. I did not travel or take advantage of any extras that required undue “adult” attention. I was expert at avoiding that. I listened to my timid voice.

“Stay invisible,” it said, “just do what is necessary to get a good grade. Then you can move on to the next phase of life. Real life.”

Flash forward eight years: I was 30 years old and in a prestigious graduate program for archaeology. I began seeing myself as a competent adult with worthwhile thoughts and interests. During these years, the more sensible voice started to make itself heard. At first a whisper, then a shout: “What is wrong with you? Why are you so afraid to be seen and heard?”

Eventually, I was able to answer that question for myself. There are many reasons we remain small and invisible, but my fears and self-defeating habits were rooted firmly in schooling. Since kindergarten, I was anxious about my teachers. They were judge, jury, and sometimes “executioner”—I witnessed corporal punishment—and I noticed that this fear of authority and many other ‘habits’ prevented me from thriving as an adult and were so self-defeating that I missed out on opportunities. When doors would open for me, personally and professionally, I was often too scared to even recognize them, much less walk through them.

Here are some Habits of Schooling, as I see them:

- Learning happens as a rhetorical conversation between the “one who knows the answer” and “those who don’t know the answer.” Passive learning is the norm.

- Learning comes in different subjects—like math, literature, biology, music, social studies—and those subjects are autonomous silos.

- People should only learn with same-age groups, and any learning environment with mixed ages is unnatural and weird.

- The younger a person is, the less they have to offer.

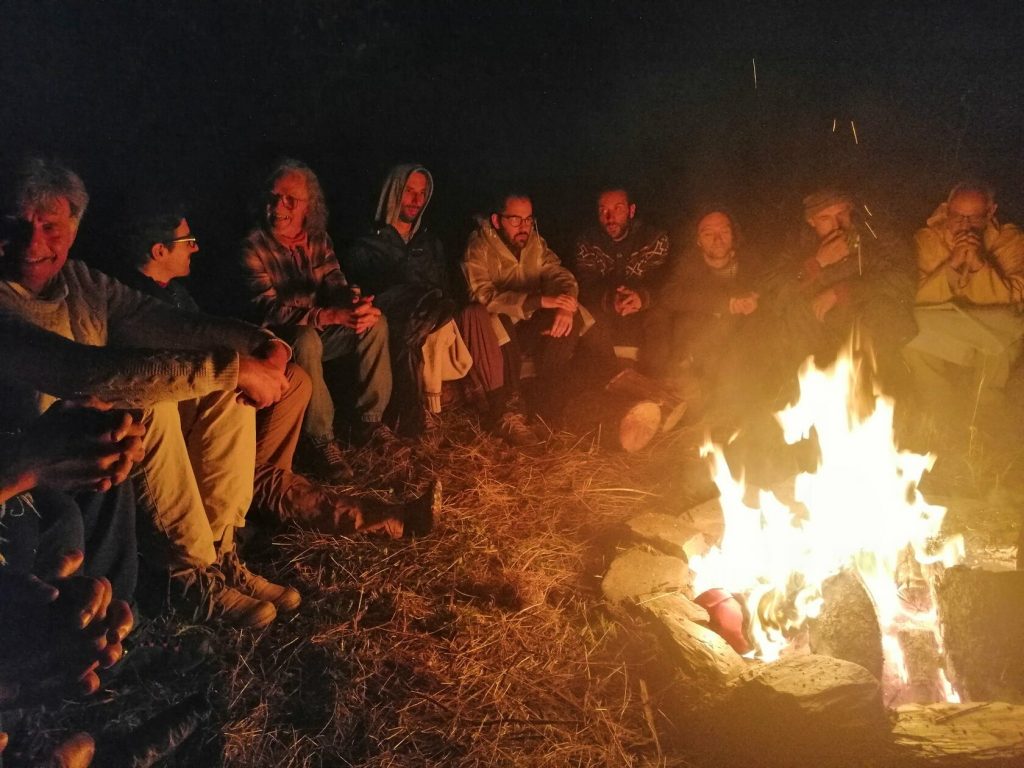

- Learning takes place indoors, in spaces with lots of books or test-tubes. Outside time is extraneous to education and only useful for “play” (not-learning) or “sport” (not-learning). Nature is a pastime.

- Grades are a competition. It is a dog-eat-dog world, and I lose if my peers win.

- Western-style education is a healthy way to learn and should be universal across cultures. Anyone not educated precisely like I have been educated is underprivileged, regardless of their culture.

- The educated elites (like me!) are at the pinnacle of human evolutionary development. We are doing vital work, bringing humanity to an intellectual utopia. It is only a matter of time.

Once I realized these axioms were profoundly flawed, I became free. I saw my schooling clearly for what it was. I also was able to set it aside and leave academia when it no longer suited me.

Charles Eisenstein speaks and writes about our cultural story and the “new story” that he and others see emerging today. He has an interest in how schooling and modern education inculcates our collective mythology and speaks about the “habits of schooling” like the ones that I identified, above. Charles takes each habit one step further, however. He notices that each habit we learn in school is a coping mechanism and comes with a mirror image of rebellion. The rebellious act— when done automatically and unthinkingly—is as much a habit of schooling as the unconscious ones.

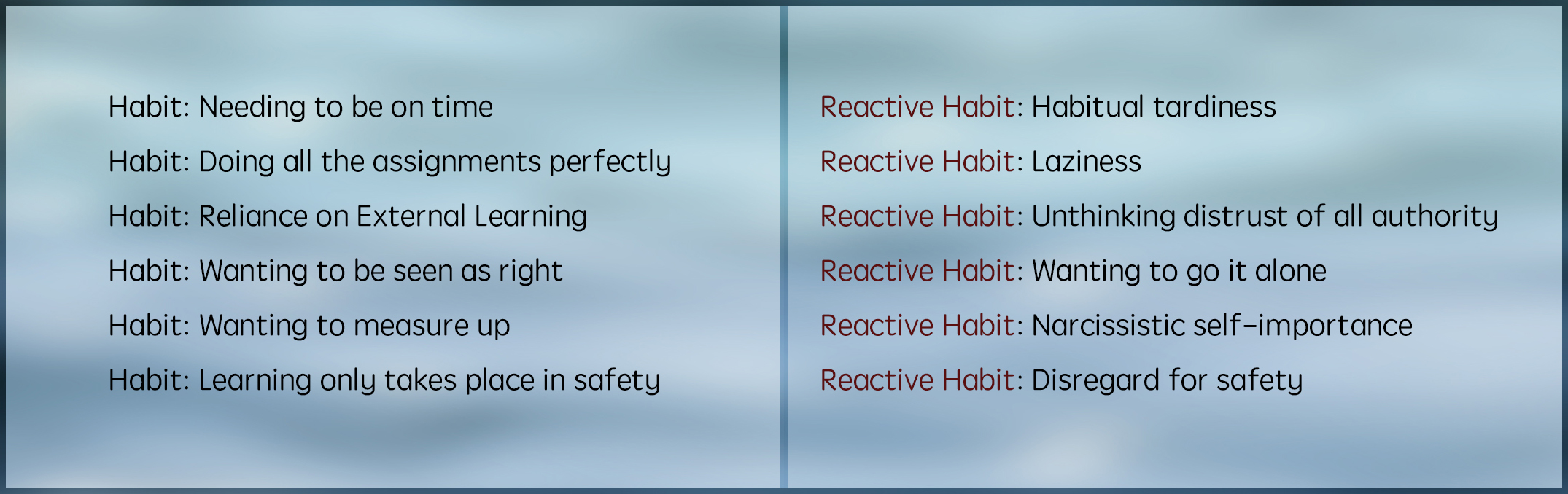

Here are some examples:

For every habit outlined, there is a reactive habit, and um, gulp, guilty as charged. Charles calls these “Habits of Submission” or “Habits of Defiance.” One might ask: “But aren’t all these habits just part of our culture at large? Where does it all begin and end?”

Well, yes, of course, that is true. However, school is the primary way that our culture indoctrinates our young into cultural norms. Family is a mitigating influence, but schools are set up to socialize our children in line with broader cultural values. That is the primary role of our educational system. And it is based on an industrial model: training workers and citizens who can read and will accept their superiors without question—making useful citizens. Today, we are ‘manufacturing’ people who will partake fully in neoliberal capitalism and consumerist culture.

The deschooling process for me is never-ending because it requires healing from the deep wounds of our culture. The good news is, there are many people out there doing this work, people who are creating networks for reskilling, mindfulness, and a “commons” to help others do this unlearning work more effectively and more deeply. There also is a growing trend to educate kids outside of the school system so that we minimize the habits of schooling for the next generation.

To unlearn our self-defeating practices, we can begin by acknowledging that working together is not ‘cheating’; that imagination is our birthright; and that thinking for ourselves is the most fundamental skill we possess as humans.

Habit: In order to be loved, one must work hard.

Habit: Your value is determined by how well you perform and by how hard you work.

Habit: Those who work the hardest have the greatest success.

Reactive Habit: workahilism, counter-productive driving and striving, doing harm to oneself by working outside ones authentic nature, lack of work/life balance, unhealthy competition, professional(academic) envy.

UGH! We have so much to unlearn!