Closer Looking | Microscopy and Aboriginal Art

Featured image | Cultural Conformity, by Graham Toomey

“This artwork captures my spiritual experience of walking along the river and gazing into the water and feeling the energy and presence of my land and people. Just as an electron microscope can allow us to visit a world far away from normality, Aboriginal spirituality too provides a world of beauty and magic that lives and survives around us.”

This exhibition is a conjunction of many strands for me as a curator. My background is as a researcher in biomedical science with a PhD in molecular biology. After years in the lab, I began collecting and managing microscopic, medical, and conceptual images for the Wellcome Trust in London. The power of these images to communicate and inspire has always been clear to me.

Ever since I was a child, I have also been interested in Aboriginal culture and art, ecological sustainability, and the need for a more integrated and holistic view of our world. So, on returning to Australia to work as Marketing and Business Development Manager for Microscopy Australia, I seized opportunities to bring stunning microscopic images to the public through touring exhibitions. – first through Incredible Inner Space and now through the creation of Stories and Structures – New Connections. These strands are all evident in this exhibition, revealing some of the rich parallels between Indigenous Australian visual story-telling and the microscopic structures hidden in the natural world. In some works, you can see that the artists have incorporated aspects of the micrographs, and in others, the artists have painted what they normally paint and let the inherent similarities reveal themselves. In indigenous cultures, important stories, holding traditional knowledge in the paintings, serve as a record of how the land and creatures were created, how they interconnect and how people relate to them.

Stories and Structures – New Connections delivers a new vision of Australia and its stories. I hope this exhibition will open new conversations and provide opportunities to make new and lasting connections and cross-cultural reconciliation. (Jennifer Whiting)

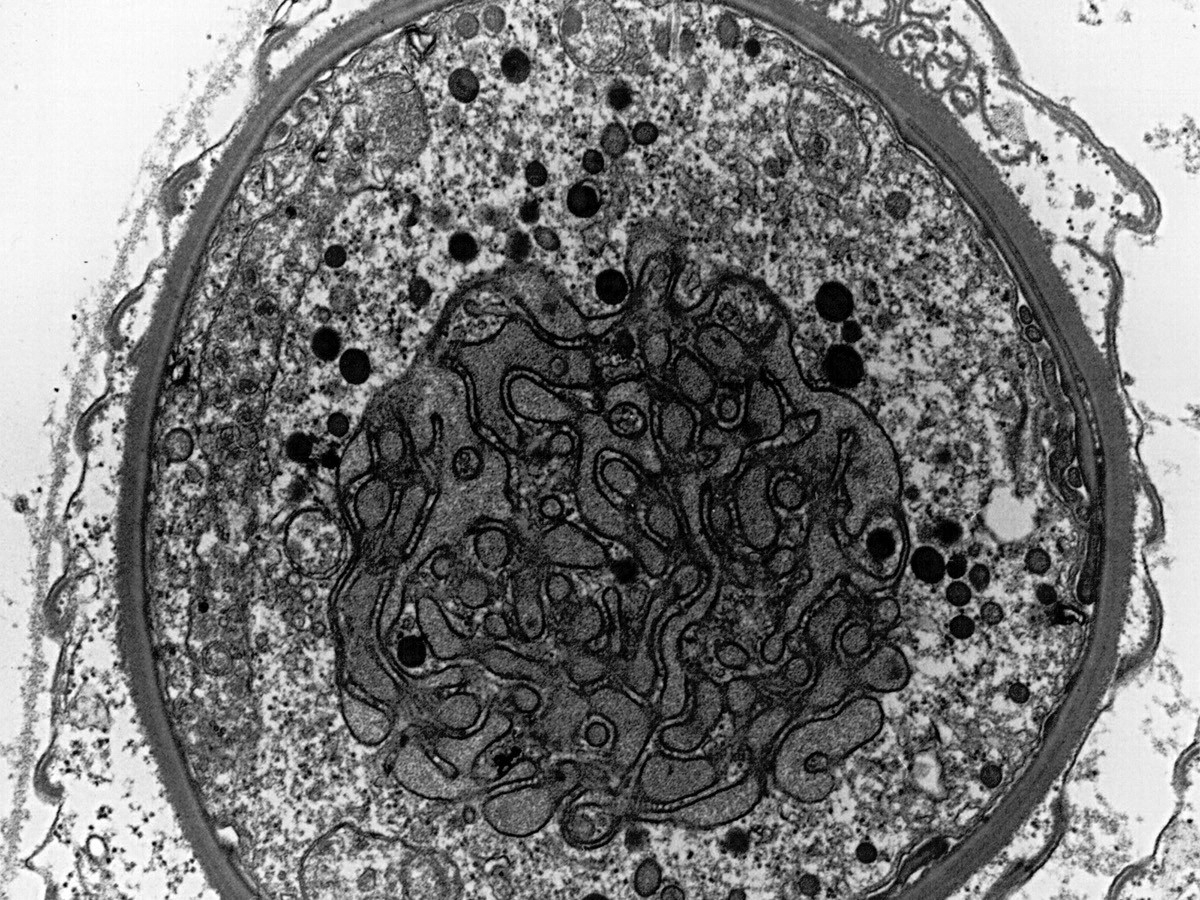

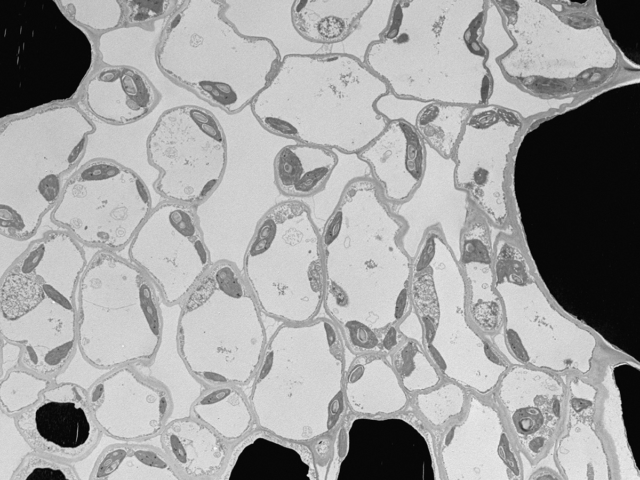

Haplosporidium parasite

These organisms mainly invade the cells of saltwater and freshwater invertebrates such as oysters, mussels, abalone, and crabs. Infestations are worst in the more intensively farmed situations and can result in considerable death and destruction.

The whole cell is approximately 5 micrometres wide. (1 micrometre is one thousandth of a millimetre).

Image: Ian Kaplin

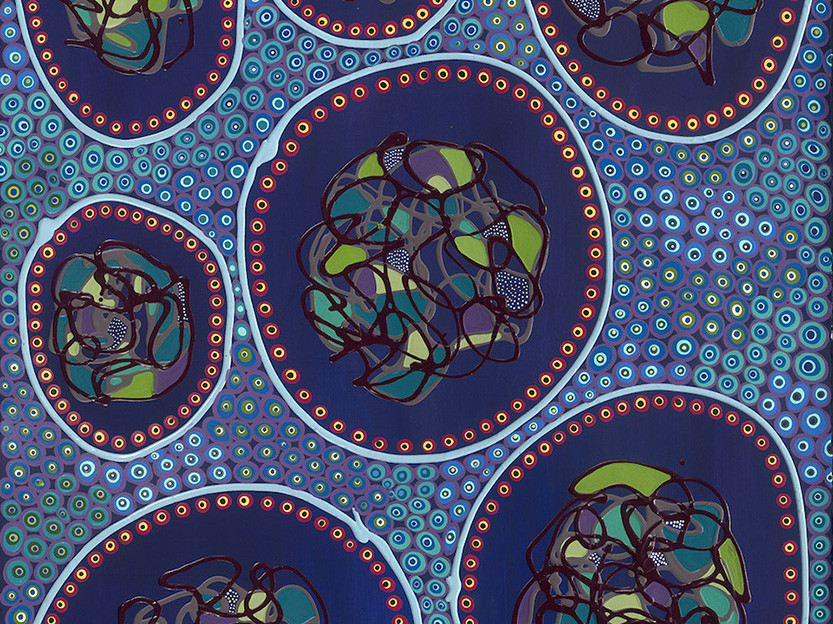

Beauty in Survival

I made the connection with colonisation in this image. As one cell (entity) is being attacked by another. I wanted to create an image that displayed the versatility, agility, and survival of different Aboriginal groups within a larger context. There is immense beauty in survival.

Artist: Bronwyn Bancroft

White Ochre

This image shows the overlapping plates found in this naturally occurring white pigment, also known as kaolin and china clay. These plates reflect the underlying arrangement of the layers of aluminium, silicon, and oxygen atoms in the crystal lattice and give the ochre its slippery feel. As well as its use as a pigment, this mineral is used in the production of porcelain, paper, cosmetics, as an aid to blood clotting, and used to treat upset stomachs and diarrhoea.

This image shows an area 185 nanometres wide (1 nanometre is one millionth of a millimetre)

Image: Hongwei Liu

Birnoo Country

This painting shows the hills of Gordon’s country, Birnoo Country. Gordon was born there, and when he grew up, he mustered cattle all throughout this country for many years—the way his father taught him to. This Country today covers what is currently known as Alice Downs Station.

As he walked across this land with family, there was always an abundance of bush food for everyone. The White Ochre micrograph reminds Gordon of the hills that surround his country, and he depicts the tonal variation through different coloured ochres employed.

Artist: Gordon Barney, Warmun Art Centre

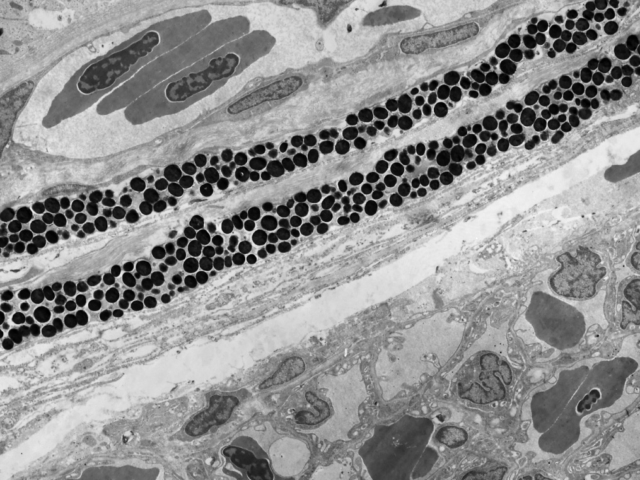

Fish Eye – Blood Flow

This micrograph shows blood vessels at the back of a fish’s eye. There are larger vessels at the top left and many smaller vessels at the bottom right.

During dry periods, many freshwater fish retreat to water holes and damp areas where they remain until rain replenishes the rivers and creeks. The widest part of the pigment granule layer is about 2 micrometres (1 micrometre is one thousandth of a millimetre).

Image: Shaun Collin

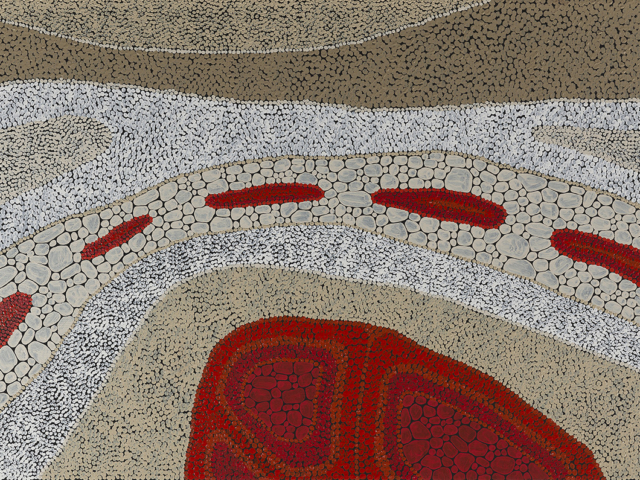

Dry River Bed

The painting is about a dry river bed. The big red area at the bottom is our camp—it is alive. The red water holes still have life. The red is the life blood.

Artist: Kurun Warun

If you like this painting, Kurun has any related ones for sale directly or through Artlandish Art Gallery, Japingka Aboriginal Art and Aboriginal Art Galleries.

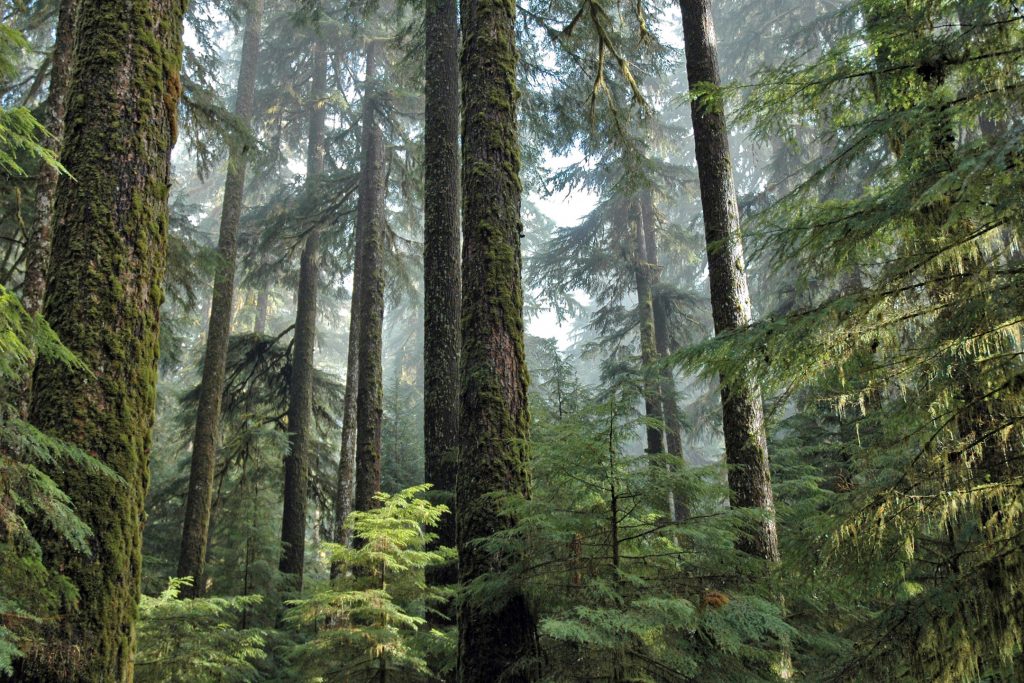

Moreton Bay Fig Leaf

Cells in a fig leaf. Like the gum leaves, the fig leaf cells contain dome-like chloroplasts that capture the Sun’s energy to make starch. The starch fuels the tree’s growth allowing it to provide food and shelter for birds, animals, and insects. These trees also provide a wealth of resources for Aboriginal people.

The identity of the black areas remains a mystery.

The area in this image is 52 micrometres across (1 micrometre is one thousandth of a millimetre).

Image: Kathryn Green

Fig Tree Leaves

The Fig Tree is very symbolic to the Yaegl people. It is the tree that is at which centre of many of the creation stories from around Maclean (NSW). Today a large Fig Tree stands proud at the centre of Ulgundahi Island, a small island in the Clarence River that my mother and her family, along with other Aboriginal families, grew up on. I chose to look deeper into the leaves of a fig tree and was fascinated to see the build-up and layering of cells that go into making these beautiful leaves. When creating this piece, it was important to represent the cellular layers within the painting as they assist in telling the story.

Artist: Frances Belle Parker

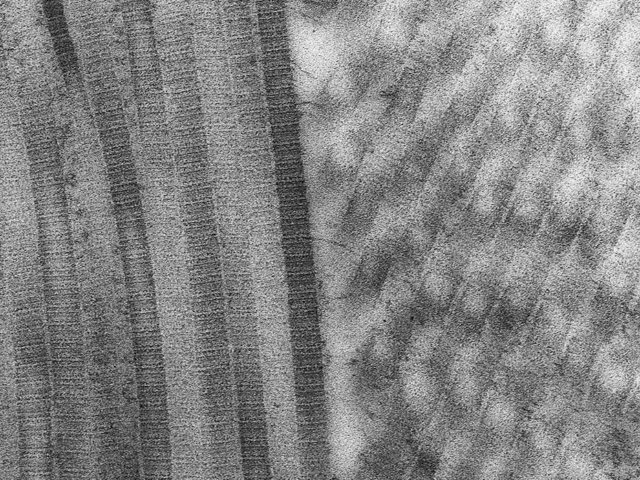

Collagen Fibrils

These long fibrils of collagen protein give skin its underlying strength and toughness. The fine lines running across the fibrils show the precise arrangement of the individual collagen molecules that make up the fibril. The ones on the left are lying flat, and the ones on the right are dipping downwards and have been sliced through at an angle giving rise to the more oval shapes. Having the fibrils running at different angles helps strengthen the skin when it is pulled in different directions. Skin can be processed into leather, and it is the intermeshed collagen fibrils that make leather so tough.

The fibrils are 75 nanometres wide (1 nanometre is one millionth of a millimetre)

Image: Anne Simpson

Skin

Skin is a celebration of my family’s Totem, the Saltwater Crocodile, and our landscape. Even though I live in the Northern Territory, part of my heritage comes from the Torres Strait and creating this work represents my Skin’s affiliations and my place there, while paying homage to my heritage. The idea is to recreate the scales of a saltwater crocodile, the flow of the water and landscape. Skin can be read as a close-up of a reptile’s skin, and as a landscape both seen from a distance and as close-up details of rocks and sand. Everything is connected—the land, the water, and us. Like the Crocodile, we are Saltwater People with an ancient lineage.

Artist: Joshua Bonson

If you like this painting, Joshua has similar ones for sale through his website.

Moth Sperm

The dark, kidney-shaped areas are called mitochondria, which provide the power to the structures composed of the circular array of dots. These nanoscale structures make the sperm tail beat so it can swim toward the egg and fertilise it. They are, therefore, essential to continuing the circle of life. For example, the witchetty grub (ngarlkirdi) is the caterpillar stage of the moth, Endoxyla leucomochla, which wouldn’t be able to breed successfully if these structures were damaged or absent.

Each circle of dark dots is 220 nanometres in diameter. (1 nanometre is one millionth of a millimetre).

Image: Greg Rouse

All images © 2019 Microscopy Australia

Witchetty Grub Dreaming

This painting depicts Napaljarri and Nungarrayi women collecting ‘ngarlkirdi’ (witchetty grubs) in an area known as Kunajarrayi (Mount Nicker) 200 km to the south-west of Yuendumu. Witchetty grubs can be eaten cooked or raw and are edible in all phases of their life cycle. The design of this painting also symbolises important features of initiation ceremonies for young Japaljarri and Jungarrayi men. The area contains many caves (‘pirnki’) overlooking an important ceremonial site associated with the Ngarlkirdi Jukurrpa. This story belongs to the Nungarrayi/Jungarrayi and Napaljarri/Japaljarri Kinship Subsections. In Warlpiri paintings, traditional iconography is used to represent the Jukurrpa, particular sites, and other elements. Circular shapes are often used to depict the important sites for the ceremony and the long straight lines represent ‘witi’ ceremonial poles, which play an important role during the initiation ceremonies.

Artist: Jennifer Napaljarri Lewis, Warlukurlangu Artists of Yuendumu

This is very helpful