Young nomad siblings bringing the family herd of Dri (female Yak) home for evening milking, Mamo Thang, Sershul nomadic area, Kham. The red prayer flags on the left will have been placed there on the inspiration of a high Lama to indicate that this is a holy place. Opposite, below the road level, is a cave used for meditation by the great Tibetan master and teacher Patrul Rinpoche.

Guardians of the Sacred in Tibet

This center of heaven,

This core of earth,

This heart of the world,

Fenced round with snow,

The headland of all rivers,

Where the mountains are high and

The Land is pure.

A country so good

Where men are born as sages and heroes

And act according to good laws.

A land of horses ever more speedy.

Anonymous Tibetan poet, 8th to 9th century

Women with traditional hair decorations

of coral and turquoise at a Lama Dance Festival.

Manigango, Kham.

The Sacred Land

Tibet is a sacred land. Its people are an expression of that sacredness. For 17,000 years, before the arrival of Buddhism, the nomads and farmers of Tibet practised Bon Shamanism which revered the land and related to it as a spiritual being. The sky, mountains, rivers, and lakes were seen to be animated by gods, demons or nature spirits, all of whom demanded careful ritual propitiation in order to create a balance between the natural and supernatural.

The establishment of Buddhism in Tibet in the 7th century transformed the country. Buddhism absorbed many Bon practices and created a culture of tremendous depth and richness – such as a devotion to the sanctity and power of natural places, studious monasticism, compassion for all living beings, and a belief in the interdependence of all beings – that the animate and inanimate are all parts of a whole. This rich culture sees the outer world as a reflection of the inner world and knows how to connect the two so that the two worlds can nourish each other.

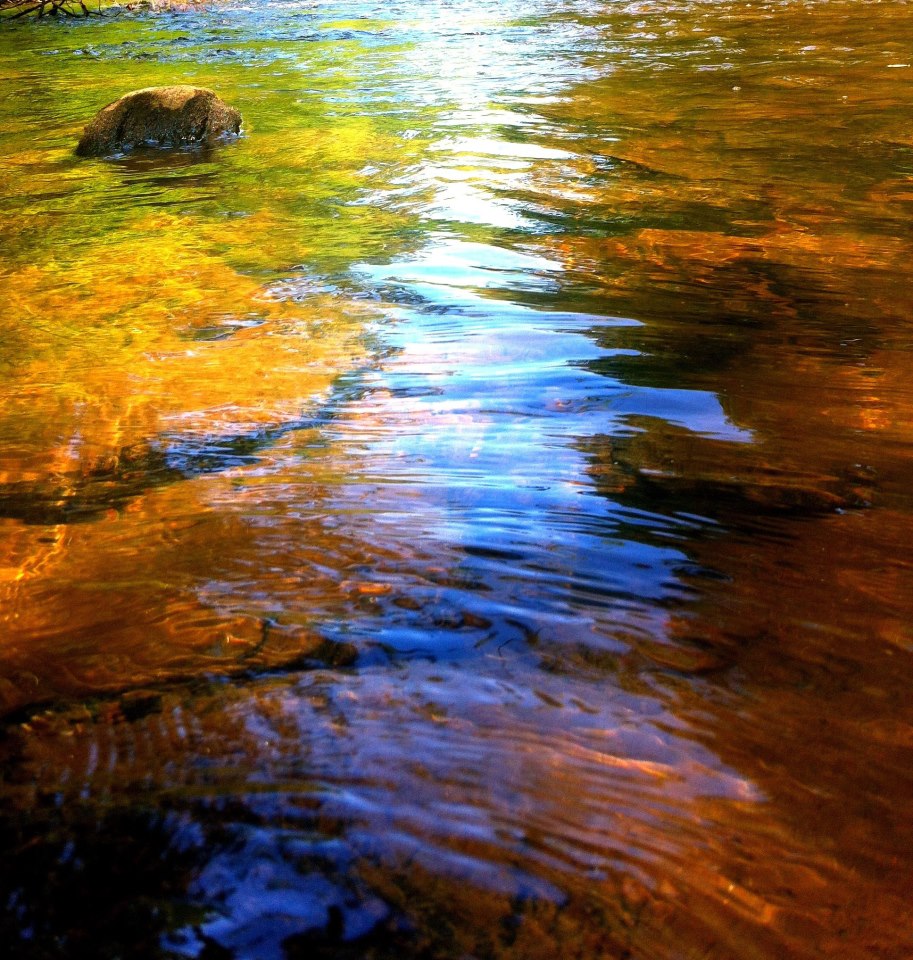

Sacred sites throughout Tibet are revered as places where these worlds meet, where the separation between inner and outer, spiritual and material, is especially thin. Mountains such as Kawa Karpo in Kham and Amnye Machen in Amdo, springs, lakes, relics, forbidden areas, places associated with spiritual figures (such as Guru Rinpoche,) and pilgrimage routes are respected as sacred. Hanging prayer flags, burning incense (usually Juniper branches), and saying prayers are just some of the traditional ways of honouring sacred sites. These practices protect the areas and their special deities; benefit the nomads, their grazing land, and their livestock.

Prayer flags surround a sacred spring near Rongpatsa, Kham.

Wisdom rediscovered

How is the worldview of Tibetan nomads (and other indigenous peoples) so relevant for the world today?

“Nomads believe that a person’s life force is connected with a locality and the spirits that dwell there and that a deterioration of this bond can have negative repercussions.”

(From Drokpa: Nomads of the Tibetan Plateau and Himalaya by Daniel J Miller)

The Tibetan nomad’s understanding of the sacred landscape brings reverence, care, and respect to the land, which is the basis of the conservation and environmental protection that the earth so badly needs today.

Once, when travelling with my Tibetan friend we arrived at her village. Local nomads came to see us as they were worried that the five springs at the foot of a local mountain, used by local people for their water supply, were drying up. These springs were considered the gift of the protector deity of the mountain, but the local authorities had turned one spring into a bathing area and another healing hot spring was full of rubbish.

The nomads were concerned that the village people no longer circumambulated the mountain that provided their water or made smoke offerings to the local goddess. It was clear from the rubbish-filled hot spring that they had forgotten the sacredness of the landscape around them. With the help of the nomads we cleaned out the spring and arranged that the nomads would make offerings to the mountain goddess.

The drying up of the springs was symbolic of a dwindling lack of respect for the environment. As the inner springs of spiritual awareness become dry, the outer springs do as well.

Environmental scientists have recently acknowledged that this traditional approach can make significant contributions to protecting endangered species and conserving biodiversity. Recognizing the value of sacred sites in contemporary conservation systems is now advocated by numerous scholars in the west and in China, and is beginning to receive increasing attention in recent times. What is needed now is not just a return to respecting the land but respect for the knowledge, skills and wisdom of those who have done so for millennia.

One of Sonam Wangbo’s sons in the spring pastures, the sacred Dahu Valley, Kham.

Spiritual Ecology

The nomads and other Tibetans hold a reverence for the natural world, which ensures that they remain stewards of the land they have lived with for thousands of years. Small pockets of awareness of the land’s magic, its sacredness, its deep inner value, still remain.

A few years ago I was travelling in Dzongsar/Meshu area, in Kham, with a friend. We stopped in Horlung Nor, a beautiful and remote nomad valley, to conduct a small prayer ceremony for Hogan, the local male protector deity who lives on the mountaintop above. This deity was also considered to be the protector of my friend’s family, and she felt it was important to make an offering to it.

Some old local nomad men came to help us, gathering Juniper for the smoke purification ritual, hanging prayer flags, and joining the simple ceremony. Afterwards, one of the nomads told us that this mountain god had appeared to him when, as a teenager, he was hunting in the forest on the mountainside. He was so surprised and terrified that he threw down his gun and fled home—never to hunt again.

One of the other nomads added: “He is lucky to be alive. My cousin saw the god when he was young and afterwards, he sickened and died.” Another one agreed: “Yes, I have heard of people who have seen the god and they generally don’t survive!”

I was amazed by the conversation, moved that a people and a place still exist where the magical and the numinous are treated as topics to chat about and where people still had such reverence for their local landscape. In the West, my experience is that people either treat this kind of topic with incredible (and depressing) cynicism or see it as a myth, an ancient story that happened somewhere else.

The land is threatened as modern culture, with its materialistic values, encroaches and as more and more nomads are settled into villages. It is not just the threat to the land one sees—the trees and lakes, the mist and grasses—but also to the inner land, enlivened with spiritual essence. As the World wakes up to the effects of environmental degradation and begins to turn back to traditional spiritual values, I hope there is a revival of appreciation for ancient Tibet’s Spiritual Ecology. As Gebchak Wangdrak Rinpoche says:

“If we have a good relationship with the earth and a good relationship with the feminine, there will be peace and balance in the world. Diseases, famine, epidemics, fighting… there isn’t peace in the world now because the earth elements are disrupted and the earth goddesses displeased. They mainly come about due to this imbalance, don’t they?

In Tibet we believe in female spirits like dakinis, earth goddesses and so forth. We believe that if we’ve disturbed or aggravated them, we must confess and do purification ceremonies to appease them. We perform confession and feast offerings, and when the dakinis are pleased the environment is peaceful. Prayers that we make to the dakinis have a special power to come true. The dakinis have also made prophecies about these things in their symbolic language.”

Gebchak Wangdrak Rinpoche

More by Diane Barker