Mountain peak near Golden, British Columbia

Rights of Nature

When you look at a mountain, your reaction is likely to be colored by what is most important to you. Skiers may think of the thrill of the trip down, climbers of the trek up. A mining executive of the coal or metals to be found there. A road engineer of the challenge of finding a way through. A photographer of the play of light and dark, mist and mystery. A conservationist ponders the preservation of majesty, ecosystems, and access for everyone. Indigenous people see brothers, grandmothers, cousins in the interplay of beings.

The last two ways of seeing have coalesced into a movement called Rights of Nature. In 2008, Ecuador became the first country in the world to enshrine such rights into its constitution. “Nature, or Pachamama,” it says, “where life is reproduced and exists, has the right to exist, persist, and maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions, and evolutionary processes.”

Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta

The importance of well-being, defined with both the Spanish buen vivir and the Quechua sumak kawsay, is the basis. It calls for the human community to “enjoy their rights, and exercise responsibilities within the framework of interculturality, respect for their diversity, and harmonious cohabitation with nature.”

In our corporation-dominant, consumption-obsessed economy, this is virtually a laughable concept, even for some who care deeply about the earth. The idea that the mountain is a being, that the rocks that form it, the plants that flank it, the rivers that fall in cascades off its edges are entities who deserve life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness is inconceivable for many and a steep climb for most. Even with their constitutional provisions, the indigenous peoples of Ecuador are still fighting an uphill battle. Mining industries, supported by the government, continually push to move into their territories.

Matanuska Glacier, Alaska

We have largely thought of rights as belonging to humans, either as individuals or groups, like states and corporations. We see the earth not as something we are part of, but something we own, a vessel for human activities, a source of products and income. Mountains are routinely destroyed for the sake of their coal. This is seen as the cost of doing business, not just for the coal company, but for all the people relying on coal to fuel their own industries and salaries. Most of the world economy depends on the exploitation of a planet that only produces so much clean water, fresh air, rich soil, and biological gain in any given cycle. Our persistent overconsumption of these blessings destroys the ecological systems that produce them. We are robbing the rest of the beings we share the planet with, as well as our own future as a species.

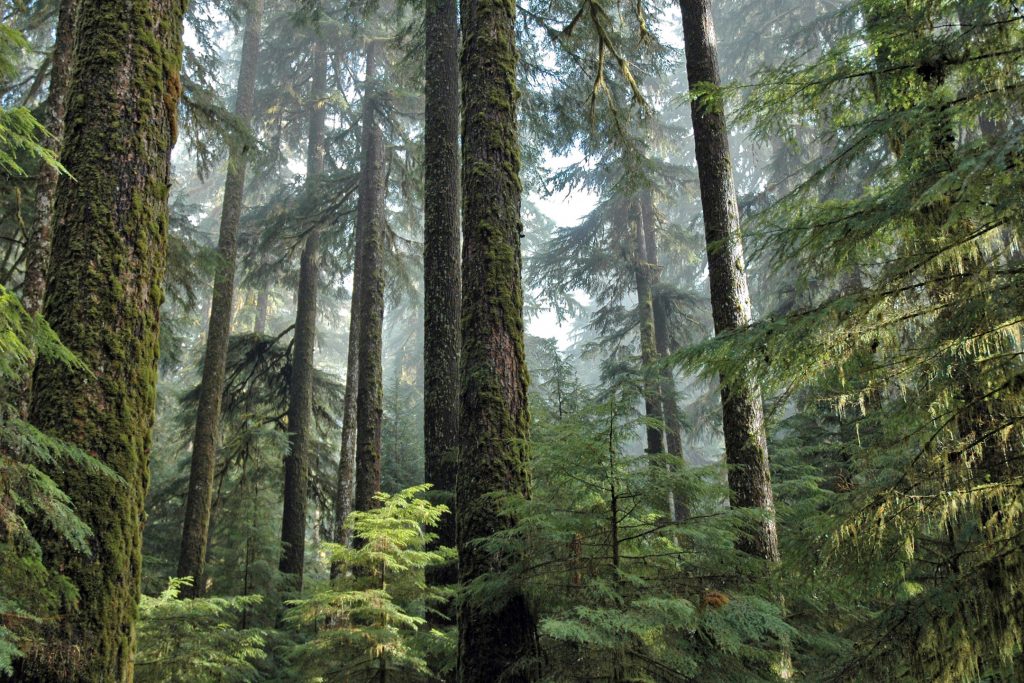

Wetland, Tongass National Forest, Alaska

Our current economic model prompts us to think of the earth in terms of its perceived value. A field growing ‘nothing’ but grasses and flowers is a ‘wasteland.’ Restrictions a town places on land ‘reduce the value of the property.’ Wetlands are one of the most important of our ecological biomes, but they are pointless from a development point of view. Developers would be mystified, if not incensed, were they expected to respect the rights of the wetlands to “live out their vital cycles” instead of filling them in for construction.

There are enormous questions and hurdles to contemplate. Does the mountain have the right to exist without being blasted with dynamite for coal or roads? Does the air have the right to be free of the mercury and sulfur in coal smoke?

Or the carbon dioxide-laden exhaust from burning oil? Does the ground under our feet have the right to a life without unnamed chemicals forced into it to frack gas? Do rivers have the right to be free-flowing, free of toxic chemicals? A home to fish and plants that in themselves carry the right to exist in peace and plenty? Do animals, including humans, have an inherent right to clean water and air?

We live in a world where we struggle to grant people who don’t look or think like us the same rights that we want. What hope is there that we will grant a field of wildflowers a right to live its vital cycles without becoming a parking lot? Yet the rights of nature are intimately tied to the rights of human beings. A series of dams in Brazil is displacing tens of thousands of indigenous people in the Amazon basin. The climate changes from our carbon dioxide-saturated atmosphere are forcing Pacific island communities to leave their flooding homelands. Development of lands sacred to indigenous peoples rob those communities not just of their place, but their history and culture, the way they define themselves. Dumping of toxic waste in poor communities because richer ones refuse it causes sickness to skyrocket in those areas. The list is endless.

Valley of the Gods, Utah

There are environmental laws worldwide. In some places they are very strict in protecting endangered ecosystems, plants and animals, and in preventing further damage. But, as we are seeing every day, these laws can be dismissed by the next administration, something that happens from the local to federal levels.

If, instead, we recognize that nature has rights of her own, their defense changes dramatically. A river, a forest, a panther, an owl, the atmosphere would then have ‘standing’ in court. A guardian or group could sue on behalf of the entity itself. Without inherent rights, the only people who have standing to sue on behalf of nature are those who are potentially or actively damaged by a policy or an infraction of a law. In practice, this often means that the case is stronger the more damage that has already been done.

This is an enormous challenge. It’s a different way of thinking for the many of us caught up in our current economic and human-centric mode of being. Changing perceptions about life on our planet and our place in it may well be the most formidable of the obstacles we face. Can we move toward seeing ourselves as part of the vast and beautiful web of life? One member among millions of beings and entities, forming a whole that we are completely dependent on. Then we can focus our extraordinary ingenuity on what Thomas Berry called The Great Work: creating a world where the human presence fosters and enhances the earth that forms and sustains us.