Rhino Conservation

I literally won an auction. It was a live auction for a trip to Namibia. That was completely on a whim, but it was a bucket list item that I always had. I am the quintessential animal lover, the little girl who was picking up the strays and the little birds. I’ve always loved animals. I’ve always liked being out in nature. I probably never would have taken the plunge to go to Africa because it was daunting to me. Where do you go? How do you figure it out? It seemed so foreign.

When I got to Namibia, the first large wildlife that I saw wasn’t a bird or baboon but a giraffe. It was actually a group of giraffes walking towards a waterhole. The sauntering and the movement of those giraffes coming above the trees, that was it for me. I was so… taken. That’s what sowed the seed.

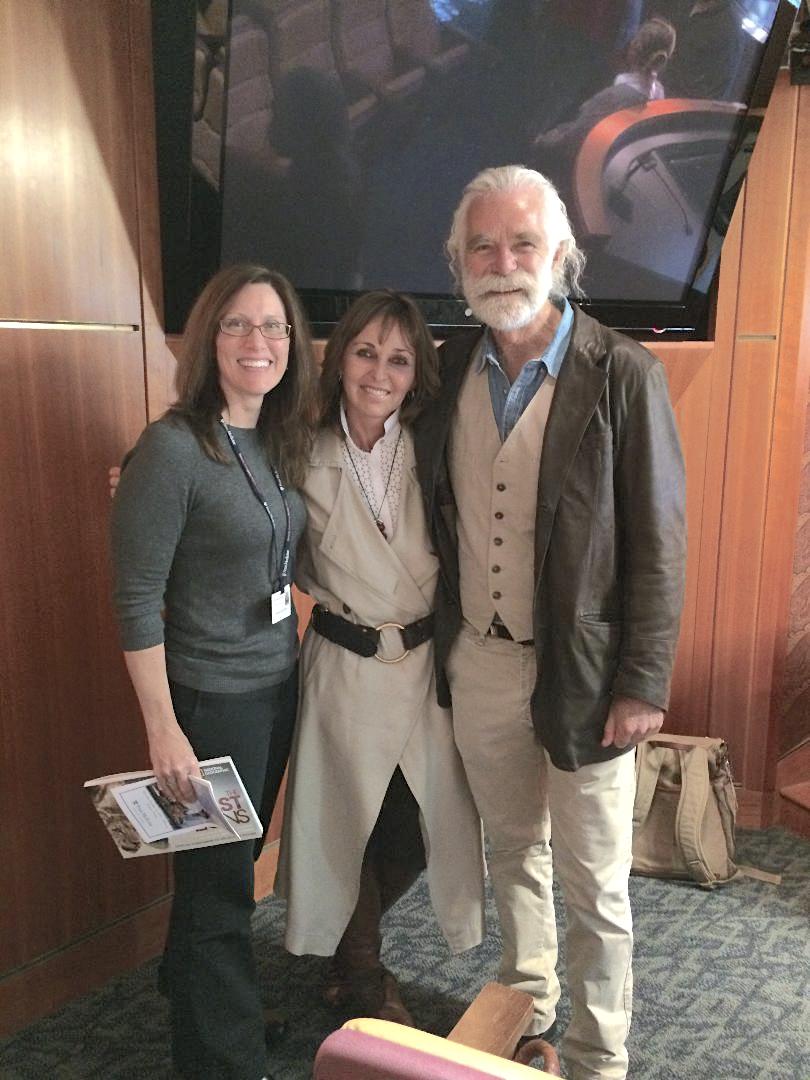

I happen to have a friend at work, Dr. Mullen of Penn Medicine, who’s also a wildlife lover who has been to Africa a number of times. He is a National Geographic supporter, and connected me with Dereck and Beverly Joubert, National Geographic Explorers-in-Residence. They were on tour in the US in the fall of 2015 for their film Soul of the Elephant which was debuting and had won some awards. The Jouberts came and spoke at the Department of Surgery at Penn Medicine on leadership from their perspective as conservationists.

Connecting with them after their talk, I had one question for them, “How can I help?”

They had just started their joint program Rhinos Without Borders. There has been lots of press around big cats and elephants. Not as many people know about the plight of the rhinos and, in fact, I did not. I said, “Fantastic. If the rhinos need help, then we are here to help the rhinos.” That was really the beginning for PARCA.

Since then, our mission has been to educate about the plight of rhinos, contribute to their conservation as well as the preservation of their larger ecosystem.

Over the last year, I’ve realized how profoundly wildlife affects people. The prior President of Botswana had a very animal-focused mentality. He was very much about the environment, very much about photographic tourism. They stopped all hunting in the country, and they’ve seen wildlife rebound.

Yet as wildlife has rebounded, it has encroached further upon humans. Women who have to go to retrieve water, are not able to get to their water source because the elephants are blocking it. Farmers are also affected by crops that get damaged. There have actually been incidents of elephants killing humans, and many other effects of their encroachment.

The new president is not as environmentally focused. He says he is more about the people and looking at what the people need, like crop protection. The environmental ministers presented him with a plan a few months ago that included elephant culling and reinstituting hunting.

As Westerners, when we make comments on social media or in petitions about ‘saving the elephants,’ some of us are intending for that to mean we have to protect the elephants and the people, but we haven’t been saying that. So the people of Botswana weren’t hearing that. What they were hearing was Westerners—who think they know the situation yet who don’t have conflict with these enormous land mammals—just saying ‘protect the elephants,’ while locals are losing family and friends sometimes to this conflict.

The Extinction Report

In the midst of our global climate crisis, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services report sheds light on the rapidly declining biodiversity and worsening health of the planet’s ecosystems. The 40-page summary for policymakers, published this May, compiles evidence from various scientific studies and reveals a reality that cannot be softened–one million species face extinction, and their loss further compromises surviving ecosystems. Without the restoration of their habitats, nearly 500,000 species will face extinction in just the next few decades.

The drive of this crisis is clear: human activity–development, deforestation, resource extraction, overfishing, hunting–as well as climate change (also largely driven by human activity) has put these species at risk. The extinction of such scale threatens human well-being, as biodiversity is foundational to our livelihoods, health, and, ultimately, our survival. The consequences of ecological and climate changes will disproportionately affect urban and poor communities.

Nearly 25% of global land is owned or tended by indigenous or local communities, and proves to be healthier than nature managed by large corporations. Appropriately, the report consults and includes local and indengeous knowledge, and contends that improving the planet’s ecological health depends on a cultural shift away from primarily valuing economic growth toward perceiving ecological health as central to human quality of life. With human activity at the center of this ecological crisis, the solution also rests in our hands, requiring systemic change across every industry.

Key findings

- Up to 1 million: species threatened with extinction, many within decades

- 33%: marine fish stocks in 2015 being harvested at unsustainable levels; 60% are maximally sustainably fished; 7% are underfished

- 45%: increase in raw timber production since 1970 (4 billion cubic meters in 2017)

- >75%: global food crop types that rely on animal pollination

- +/-821 million: people face food insecurity in Asia and Africa

- 68%: global forest area today compared with the estimated pre-industrial level

- 29%: average reduction in the extinction risk for mammals and birds in 109 countries thanks to conservation investments from 1996 to 2008; the extinction risk of birds, mammals and amphibians would have been at least 20% greater without conservation action in recent decade

Dereck and Beverly Joubert

Dereck and Beverly Joubert are globally recognized wildlife conservationists, National Geographic Explorers-in-Residence, award-winning filmmakers, and photographers. They are the founders of the Big Cats Initiative with National Geographic, which funds 86 grants in 27 countries for the conservation of big cats. The Jouberts have been researching in Africa for over 30 years and are prolific in their conservation work. They have made 25 films for National Geographic, published 11 books, six scientific papers, and written many articles for National Geographic Magazine. They have received 8 Emmy Awards, a Peabody Award, a Grand Teton Award, multiple Golden Panda Awards, a World Ecology Award, and a Presidential Order of Merit awarded by Botswana’s president, Seretse Khama Ian Khama.

One of the most beneficial things that the Jouberts did for me personally and for PARCA as an organization was to extend their full support to us, ‘What we have at our disposal, you have at your disposal,’ they assured me. ‘Use what you can, because we’re all partners in this. There’s no competition. If you’re jumping on board and we’re all going to do this, we’re going to do this together and we all have to support each other.’ Their generosity came in the form of advice and expertise, access to their staff, and even their portfolio of photography–Beverly Joubert-quality photography, of course.

Beverly Joubert is an acclaimed photographer, and her exhibitions have furthered the reach of their mission. The Jouberts recently launched Rhinos Without Borders in partnership with Great Plains Conservation and And Beyond which aims to move 100 rhinos from South Africa to Botswana to save them from the poaching crisis.

It’s complex, and we can’t do it without the locals involved in the conversation. Understanding the disruption of social structures to both humans and animals is critical in the work of conservation.

It’s complex, and we can’t do it without the locals involved in the conversation. Understanding the disruption of social structures to both humans and animals is critical in the work of conservation.