Rebuilding Earth’s Forest Corridors

“Islands are where species go to die.”

When I first heard that David Quammen quote, I thought of Darwin and the Galapagos Islands, and of Australia and other places where evolution had cruelly terminated entire species and developed others along sometimes strange and bizarre paths. It made sense that these effects were all due to extreme isolation.

I had no idea then that I would one day be concerned that we are also creating islands everywhere we develop and contributing to the destruction and mutation of species all around us. As far as nature is concerned, an island need not be a land mass surrounded by water. It can simply be a city block.

Nature tends to live in ribbons—the forest corridor, the mountain range, the coastline, and the winding river. Any ecosystem that is disconnected from similar (or different) ecosystems will eventually die. Any ecosystem separated by a boundary from the ecosystems around it exists as an island, and the effects are the same. England successfully addressed this issue in the mid-twentieth century with greenbelts. Queen Elizabeth I created the first greenbelt around London in 1580. She envisioned a three-mile-wide parkland band around the city to stop the plague from entering London, but it was never fully realized. Modern UK greenbelt policies date to the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which allowed local authorities to include greenbelts in town plans. Today about 13% of England’s total land area is designated as greenbelt. The greenbelt was England’s response to rapid urbanization and population growth resulting from industrialization. It is still a very effective antidote to urban sprawl and the industrial erosion of quality of life.

As our world moves toward higher populations everywhere, we would all do well to consider this innovative example of good planning. Even where land seems abundant, as it does in North and South America, we would still be wise to work within natural patterns. For countless generations we designed and built in tune with our Earth. But ever since the industrial revolution, we have become increasingly invested in the “grid” and in the orderly control of natural features. Unfortunately, our block grid systems create islands that defeat the interconnected energies of ecosystems and the biomes they are part of.

In land development, we always speak first of a site or a lot. In our minds, we envision the legal parcel that we are dealing with. It comes with boundaries that are artificial and typically have little or no relationship to the physical qualities of the land, both within and beyond those boundaries. Through our terminology we abstract the idea of the earth, and of the dirt and terrain we are dealing with. If that was as far as it went, it might be all right, because it serves the legal and financial worlds that are so tied in to our development industry.

But we unfortunately take it further.

If we are developing a site, we often reinforce its boundaries with roads, sidewalks, foundation walls, and other physical barriers. The bounded site, regardless of how well it is treed and planted by us, can become an ecological island, and it will trend toward failure over time.

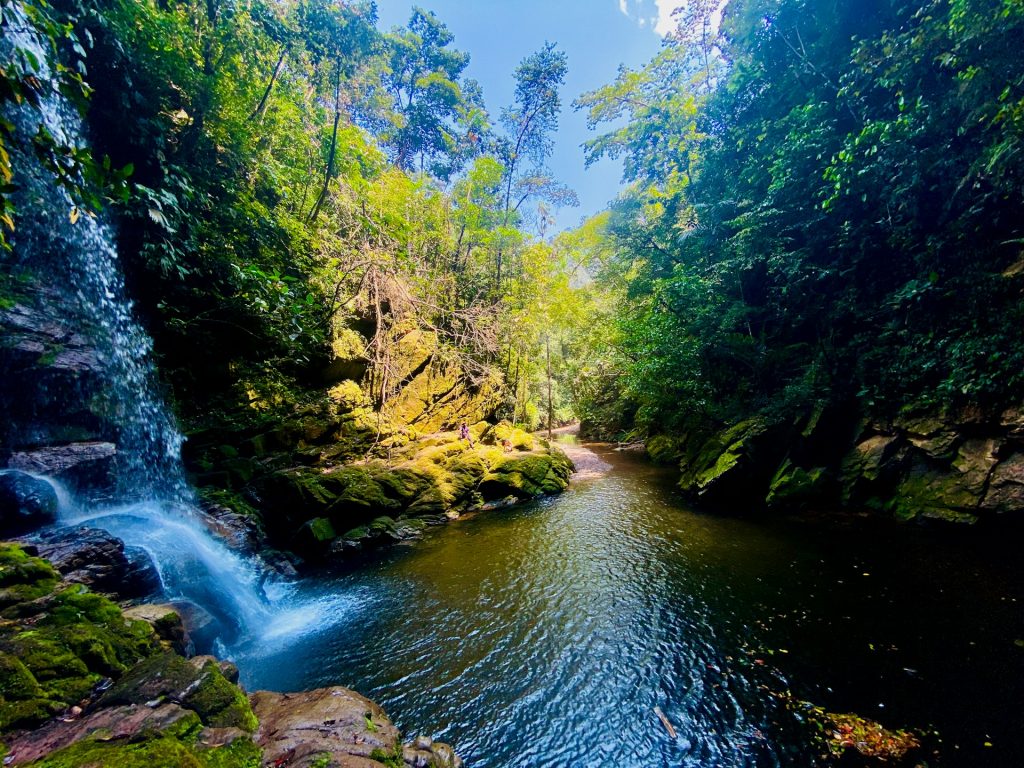

Waterways and Forest Corridors

Let’s look at trees.

We plant them because we love trees; they provide shade, clean and oxygenate the air, filter the sunlight, and rustle in the wind. Many varieties flower in the spring and shower us with blossoms. We all love trees. But we don’t always understand what they really need to thrive. First, they obviously need water. But they also need something else.

Nature depends on all its members for its strength.

A separated tree will often weaken or die because it is not protected from the wind. Most trees will need a connected tree canopy and root system for them to be able to thrive. They also serve as a canopy connector for the myriad members of the insect, bird, and small-mammal worlds that travel across their branches, moving from tree to tree.

Trees not connected to each other at the canopy and root levels can become susceptible to disease and pests. We have to fertilize them. We have to spray them with pesticides. More importantly, when trees are not connected at the canopy and root levels, they do not support a vibrant ecosystem at all, and we are eventually left with barren spaces.

When we break a line of trees so that the canopy and roots cannot touch across a road, or a lane, or even a park, we have crippled the forest as an effective ecosystem and left each tree as a lone survivor that may not thrive, may not propagate, and will fail to support the larger biome as it is designed to do.

In many cities we are now looking at planting one tree per person, which is a laudable goal. But we must remember to plant the trees where they can begin to re-create the forest corridors we have removed and disrupted.

It can be difficult to visualize where forests grew before the city. Using satellite imagery, we can now trace the outline of previously forested areas. They show as darker areas on the satellite image. If we restore trees along these corridors, they have a much greater chance of thriving. Old forest corridors are always above underground waterways, and they source the subsurface water through their root systems. Ignoring the natural feature of the old forests wastes an opportunity to more easily restore a partial ecosystem, with all the intrinsic benefits its trees bring to us. Furthermore, establishing trees above subsurface water increases their drought resilience.

Too often we think of the city and the country, or the woods, as separate. Good land management respects the intertwined quality of the relationship. I prefer to use the word stewardship when referring to land-management practices, because I think it reflects the intergenerational quality of the effort required. When we speak of the country or the woods near our cities, we now refer to the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Wherever urban development abuts a wildland, we have a WUI. Modern stewardship practices are evolving to restore the health of these wildlands. Proper wildland stewardship, including increasing drought resilience and the regular clearing of brush and dead wood, reduces the risk of uncontrolled wildfires. But until their health is restored, these WUI zones are where we will continue to see wildfires encroaching into urban areas.

Wildfires in the western United States occur nearly four times more often today than they did in the 1980s. They threaten lives, increase local air pollution, and put areas at risk of flash floods when the rains do come.

Satellite-based fire maps of the world show natural seasonal burning patterns like the summer fires in Canadian boreal forests. These images also show unnatural man-made fires like the August–October Amazon rainforest burns and the Africa and Southeast Asia agricultural burning during the dry season. Such burning always results in thick smog over the broader region. The Indonesian fires are so bad that Singaporeans hundreds of kilometers away are often forced to take refuge indoors for weeks until the burning season is over.

Unfortunately, natural burning patterns have been disrupted. When residents don’t allow controlled burns through the forest understory, fuels build every year. Wildfire risks are exacerbated when we disallow proper wildland stewardship practices at urban boundaries. Without proper WUI guidelines in place, and special building codes for these high-hazard areas, the harm will continue. WUI guidelines include reducing fuel by clearing out bush, increasing drought tolerance of wildlands, and building noncombustible construction with good water supply for sprinklering. It is time-consuming and costly to develop and implement WUI guidelines and codes. These WUI guidelines and codes are new to our industry, and we can’t implement them fast enough! Canadian, American, European, and Australian wildfires of recent years have been terrifying and far more costly than preventative measures might have been.

Up close and personal, a firestorm’s real psychological effects on a community are devastating. I was in Edmonton for a board meeting while the 2016 Fort McMurray fires were burning. When I arrived, my hotel was full of children in pajamas and adults with nothing but the clothes on their backs, all forced to flee their homes in the middle of the night. The children had lanyards around their necks identifying them as they ran around the hotel lobby. The parents sat in the restaurant, many without wallets or identification. I gave up my room and stayed at the CEO’s home so one more family would have beds. I flew home sitting next to a thirty-five-year-old woman and her sixty-five-year-old father. They smelled of smoke. They showed me pictures they managed to take of the wildfire as it came down their street. Literally a towering inferno, it destroyed everything in its path, including their home. They were very lucky to escape alive. They planned to stay with family in Vancouver but were in shock, with no idea of how they would ever be able to pick up their lives again.

It was heartbreaking.

The fires we see now are so extreme they are called “mega-fires” and “firestorms” by firefighters, who live in fear of them because they are so often powerless to stop them. A recent study by the University of Leicester determined that wildfires are most likely to occur at the wildland-urban interface when wise forest and wildland stewardship practices are abandoned.

Trees, and the ecosystems and biomes they support, are critical to our survival. Thinking in terms of isolated “sites” and “lots” makes it very difficult for us to rethink things around forest corridors and greenbelts. We must stop trapping trees in isolated “grid-islands,” for their health and our own. We should plant trees in the forest corridors they belong in, connecting their roots and canopies. It is essential that we broaden our understanding of the forest biome and the stewardship it requires, especially at the urban-wildland boundaries.

When properly employed, trees reduce the heating effect of city asphalt. Trees can also reduce rates of respiratory ailments in polluted areas. They shade buildings directly and reduce the energy requirements for cooling. Trees make urban areas more bearable and pleasant, providing visual stimulation and, like the campfire, draw our eyes and calm our mental processes. The roots of trees aerate the soil and fertilize it, creating a subsurface ecosystem.

We need to understand how to protect them.

From Rebuilding Earth: Designing Ecoconscious Habitats for Humans by Teresa Coady, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2020 by Teresa Coady. Reprinted by permission of publisher.

From Rebuilding Earth: Designing Ecoconscious Habitats for Humans by Teresa Coady, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2020 by Teresa Coady. Reprinted by permission of publisher.