Quiet Forest, from One Square Inch of Silence

Quiet Places Initiative

Gordon Hempton is a natural born listener. Known as the Sound Tracker®, he is an acoustic ecologist dedicated to capturing and preserving one of Earth’s most precious experiences on the verge of extinction: silence. With unprecedented levels of noise pollution, the world and its inhabitants suffer from more than just the annoyance of highway traffic and urban activity; the impacts of overexposure to unnatural noise are reflected in poor mental and cardiovascular health, and even anti-social behavior.

For Gordon, silence is about reconnecting—to nature, and to each other. He has committed his life’s work to seeking and protecting the quietude we all crave. He has circled the globe three times, recording quiet spaces with equipment that replicates the three-dimensional quality of human hearing. His book, Earth Is a Solar-Powered Jukebox, offers a guide to listening, recording, and sound designing with nature, and his book, One Square Inch of Silence (excerpt below) details one of the United States’ quietest places, the Hoh Rain Forest of Olympic National Park.

Preserving rare spaces of silence has become a worldwide endeavor for Gordon. He and co-founders Tim Gallati, Karl Kramer, and Vikram Chauhun have established Quiet Parks International to identify and protect places around the globe that are truly free from noise pollution.

This sound gallery is a collection of audio samples that Gordon has recorded around the world. We invite you to experience these rare moments of ‘silence.’ — Victoria Price, for Kosmos

Quiet Parks International

Quiet Parks International, formerly known as the One Square Inch of Silence Foundation, is committed to the preservation of Quiet for the benefit of all life. Launching on Earth Day 2019, QPI aims to identify and protect rare, quiet places that are free from the noise pollution that overwhelms our planet. With the ever increasing sonic burden of highways, air and shipping traffic, silence is nearing extinction and this initiative is needed now more than ever. To join the efforts in creating a worldwide network of pristine silence and solitude, visit Quiet Parks International.

Sound Gallery

Dawn

Amazon, Ecuador

We are listening to dawn arrive in the Ecuadorian Amazon. This is the heart of biodiversity and the lungs of the planet. One by one, each animal species takes its turn to announce themselves, re-establish territory, and perhaps even attract a mate. Some animal species are blind, however, no animal species are deaf.

Wood Frogs and Thunder

Sri Lanka

I set up my recording gear cautiously high on a mountain in Sri Lanka. The sun was setting. Soon I would be all alone. A prevailing wind pushed clouds against the trees causing drips that attracted my attention. Soon there were wood frogs hiding under the leaves, so small that I never saw any. Each gave long, punctuated accents to the space. The final touch to this unforgettable moment was added by an approaching thunderstorm. (Note: I use a microphone system that replicates human hearing, and because I do not edit my recordings, you are not experiencing my studio artistry but rather the sonic beauty of this planet worth saving.)

Riparian Zone

Belize

We are near Mayan ruins in Central Belize that have been reclaimed by the jungle—a haunting reminder that even great civilizations can vanish unexplained. Life’s necessity is water which instantly draws our attention to the foreground while a distant howler monkey expands our auditory horizon to the far background. For years, I believed I recorded sound, but now I know I record space made audible by sound—that is what keeps me on the hunt around the world for my next nature sound portrait.

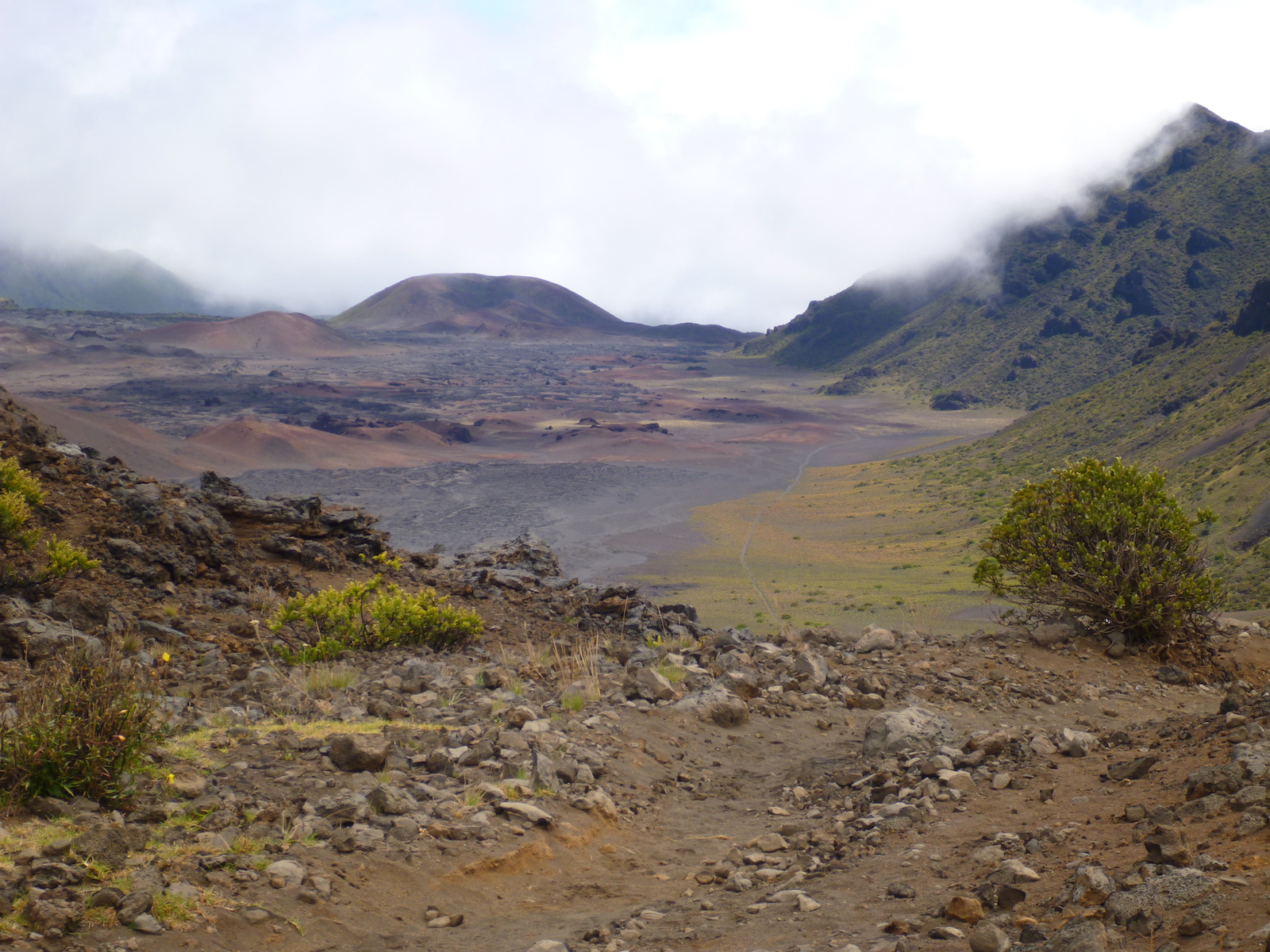

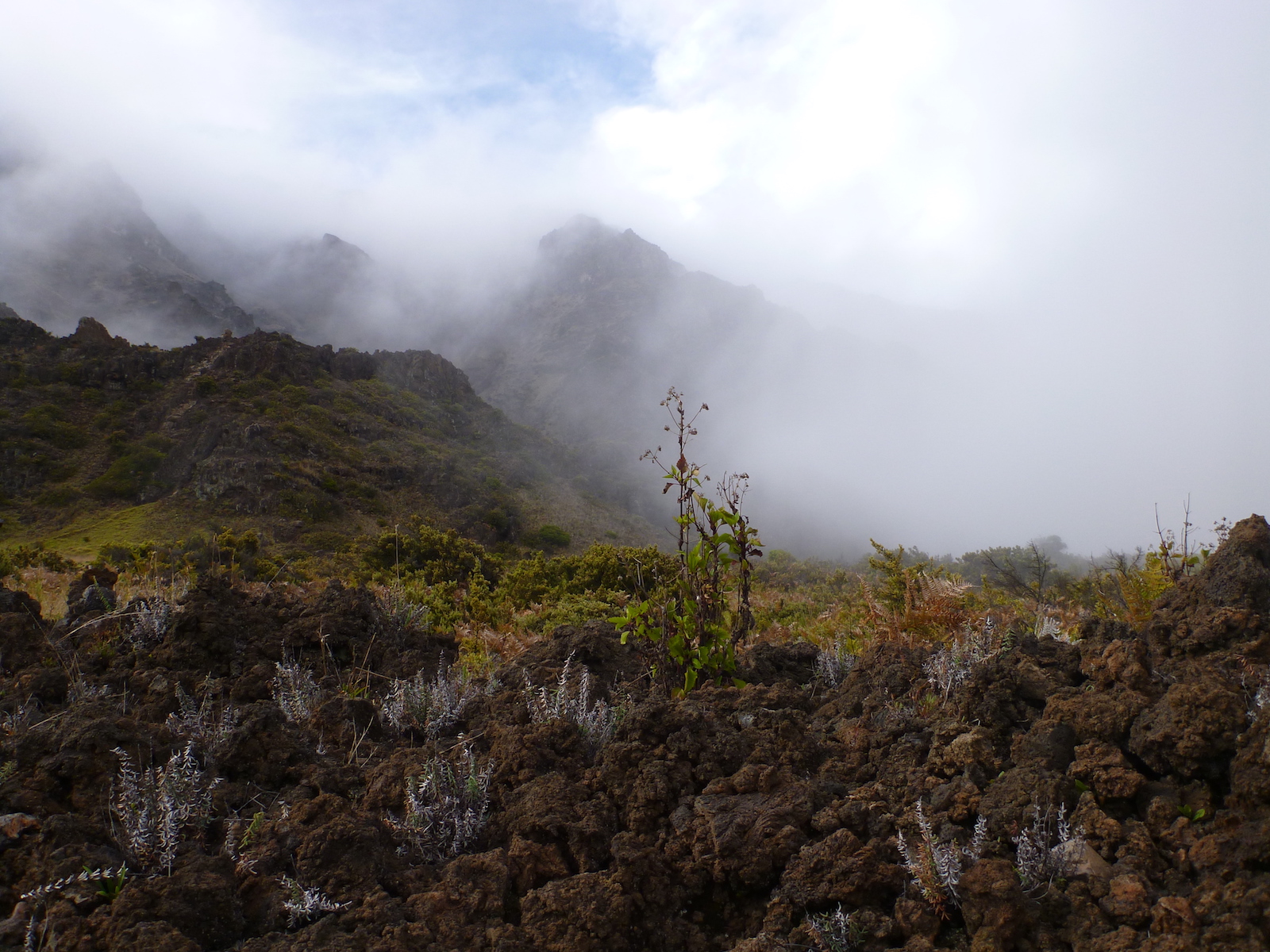

Haleakala Wind

Hawaii, U.S.

Haleakala Volcano, Hawaii, rises more than 3,000 meters above sea level, then its crater sinks 1,000 meters back towards the Earth’s center, forming a natural acoustic isolation chamber complete with sound adsorbing volcanic sand. Haleakala Crater is the Quietest Place on Earth; calculated sound pressure levels are in the negative decibels on windless days. Today, silence is made audible by trade winds that skirt the volcano’s rocky rim.

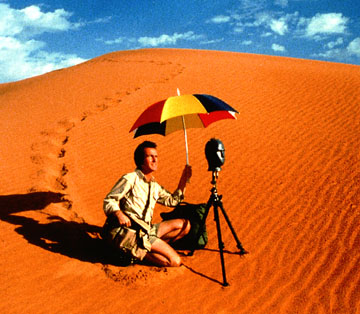

Gecko Lizards

Kalahari Desert, South Africa

I arrived on the scorching sands of the Kalahari to record birdsong, but because it was the seventh year of a draught, there were no birds to record. Frustrated and temporarily disheartened, the sun set, and as it did these gecko lizards began their mocking evening chorus that documents their triumph. Just one example of nature’s important lesson: disappointment is often an epiphany in disguise.

Book Excerpt | One Square Inch of Silence

Washington, U.S.

Everything that you have heard here is unprotected and rapidly vanishing. While we have Dark Sky Parks that protect our view of the Celestial Sea, there is not one Quiet Park where we can listen to nature’s concerts undisturbed to take on an equally awe-inspiring view of life. On Earth Day 2005, I decided to change this when I hiked up the Hoh River trail in Olympic National Park near my home and placed a small stone on a moss-covered rock. I promised to defend it from all noise pollution. Nearly 12 years later, three airlines have altered flight paths to avoid the park. Because of the way sound travels differently than light, protecting one square inch of silence manages more than 1,000 square miles. You can find out more about the effort to create the world’s first Quiet Park at www.quietparks.org.

Prologue | Sounds of Silence

“The day will come when man will have to fight noise as inexorably as cholera and the plague.”

So said the Nobel Prize–winning bacteriologist Robert Koch in 1905. A century later, that day has drawn much nearer. Today silence has become an endangered species. Our cities, our suburbs, our farm communities, even our most expansive and remote national parks are not free from human noise intrusions. Nor is there relief even at the North Pole; continent-hopping jets see to that. Moreover, fighting noise is not the same as preserving silence. Our typical anti-noise strategies—earplugs, noise cancellation headphones, even noise abatement laws—offer no real solution because they do nothing to help us reconnect and listen to the land. And the land is speaking.

We’ve reached a time in human history when our global environmental crisis requires that we make permanent life style changes. More than ever before, we need to fall back in love with the land. Silence is our meeting place.

It is our birthright to listen, quietly and undisturbed, to the natural environment and take whatever meanings we may. Long before the noises of mankind, there were only the sounds of the natural world. Our ears evolved perfectly tuned to hear these sounds—sounds that far exceed the range of human speech or even our most ambitious musical performances: a passing breeze that indicates a weather change, the first birdsongs of spring heralding a regreening of the land and a return to growth and prosperity, an approaching storm promising relief from a drought, and the shifting tide reminding us of the celestial ballet. All of these experiences connect us back to the land and to our evolutionary past.

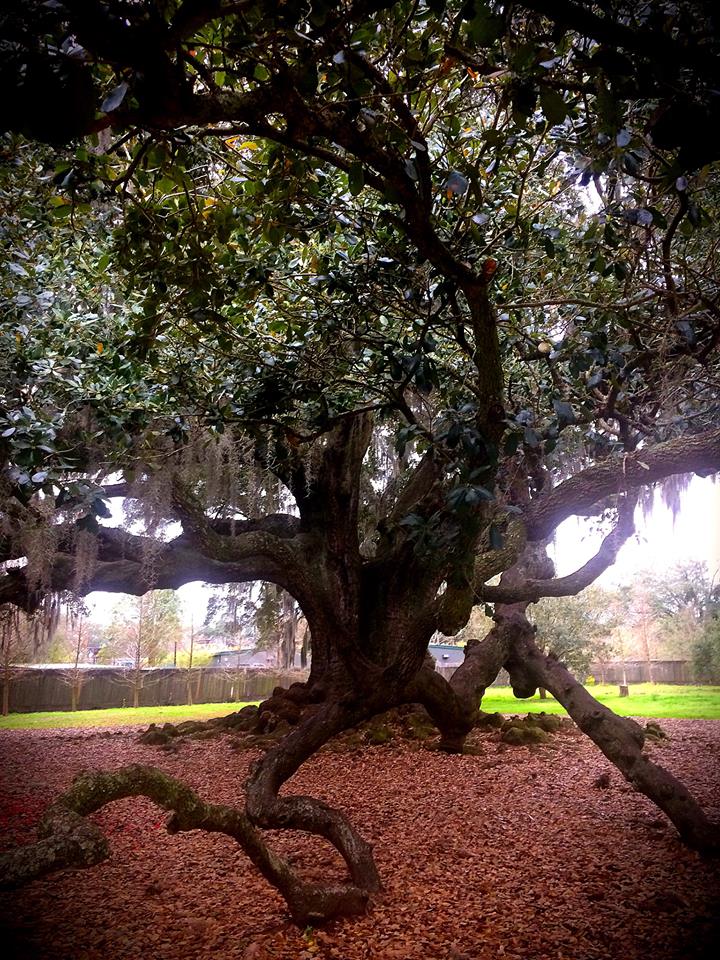

One Square Inch of Silence is more than a book; it is a place in the Hoh Rain Forest, part of Olympic National Park—arguably the quietest place in the United States. But it, too, is endangered, protected only by a policy that is neither practiced by the National Park Service itself nor supported by adequate laws. My hope is that this book will trigger a quiet awakening in all those willing to become true listeners.

Preserving natural silence is as necessary and essential as species preservation, habitat restoration, toxic waste cleanup, and carbon dioxide reduction, to name but a few of the immediate challenges that confront us in this still young century. The good news is that rescuing silence can come much more easily than tackling these other problems. A single law would signal a huge and immediate improvement. That law would prohibit all aircraft from flying over our most pristine national parks.

Silence is not the absence of something but the presence of everything. It lives here, profoundly, at One Square Inch in the Hoh Rain Forest. It is the presence of time, undisturbed. It can be felt within the chest. Silence nurtures our nature, our human nature, and lets us know who we are. Left with a more receptive mind and a more attuned ear, we become better listeners not only to nature but to each other. Silence can be carried like embers from a fire. Silence can be found, and silence can find you. Silence can be lost and also recovered. But silence cannot be imagined, although most people think so. To experience the soul-swelling wonder of silence, you must hear it.

Silence is a sound, many, many sounds. I’ve heard more than I can count. Silence is the moonlit song of the coyote signing the air, and the answer of its mate. It is the falling whisper of snow that will later melt with an astonishing reggae rhythm so crisp that you will want to dance to it. It is the sound of pollinating winged insects vibrating soft tunes as they defensively dart in and out of the pine boughs to temporarily escape the breeze, a mix of insect hum and pine sigh that will stick with you all day. Silence is the passing flock of chestnut-backed chickadees and red-breasted nuthatches, chirping and fluttering, reminding you of your own curiosity.

Have you heard the rain lately? America’s great northwest rain forest, no surprise, is an excellent place to listen. Here’s what I’ve heard at One Square Inch of Silence. The first of the rainy season is not wet at all. Initially, countless seeds fall from the towering trees. This is soon followed by the soft applause of fluttering maple leaves, which settle oh so quietly as a winter blanket for the seeds. But this quiet concert is merely a prelude. When the first of many great rainstorms arrives, unleashing its mighty anthem, each species of tree makes its own sound in the wind and rain. Even the largest of the raindrops may never strike the ground. Nearly 300 feet overhead, high in the forest canopy, the leaves and bark absorb much of the moisture, until this aerial sponge becomes saturated and drops re-form and descend farther, striking lower branches and cascading onto sound-absorbing moss drapes, tapping on epiphytic ferns, faintly plopping on huckleberry bushes, and whacking the hard, firm salal leaves, before, finally, the drops inaudibly bend the delicate clover-like leaves of the wood sorrel and drip to leak into the ground. Heard day or night, this liquid ballet will continue for more than an hour after the actual rain ceases.

Recalling the warning of Robert Koch, developer of the scientific method that identifies the causes of disease, I believe the unchecked loss of silence is a canary in a coal mine—a global one. If we cannot make a stand here, if we turn a deaf ear to the issue of vanishing natural quiet, how can we expect to fare better with more complex environmental crises?

Gordon Hempton

Snowed in at Joyce, Washington