Wrestling with Wealth and Class

It was one of those big fundraising dinners. Honoring a major donor, charging who-knows how much a plate to bring in more money and put the event squarely on the radar of the local high society. This time it was my grandparents who were the major donors, and I was sitting at a big circular table with my cousins who had gathered to celebrate and support our beloved grandparents. It was one of those tables with the white cloth, artfully folded napkins, and more sizes of forks than I really knew what to do with. I felt an uncomfortable, but not unfamiliar, combination of gratitude, guilt, pride, and shame.

My grandparents are incredible. Perfectly imperfect products of their time motivated by love of family and search for security and belonging amongst a society that was completely alien to their own immigrant parents. Their rise to wealth had something to do with my grandma working two jobs to help my grandfather through med school; something to do with my grandfather becoming a cardiologist in South Florida as Medicare made the profession more profitable; something to do with my grandparents betting it all to buy some real estate just before a boom; something to do with my grandmother managing that real estate epically; and something to do with more real estate and a skillful navigation of stock and bond markets. And all this happened during a time when folks didn’t want them living on their block because they were Jewish.

The story also has do with the fact that passing as white afforded them some opportunities. It has to do with the growth of the American economy, generally, which in turn has to do with rules about who was able to participate where and when; the foundations laid by slavery; the attacks on organized labor; the development of convoluted financial markets; the wars and policies created to maintain the value of the American dollar; and the relentless extraction of life force from people and planet that weave themselves into the story of the American dream and the growth of the American economy that created the possibility for my grandparents’ investments to grow.

Everything’s connected.

I love my grandparents. I’m grateful for them. I’m impressed and amazed by them. They have given me material security inside an economy that preys on insecurity. This security has created respite from the constant water-treading that characterizes most lives inside capitalism, and that respite has provided the space for me to focus on my integrity, my love, and my gifts.

That’s where this familiar swirl of gratitude, guilt, pride, shame, and responsibility comes from. But as I sat at that table with my cousins, the whole thing hit another gear.

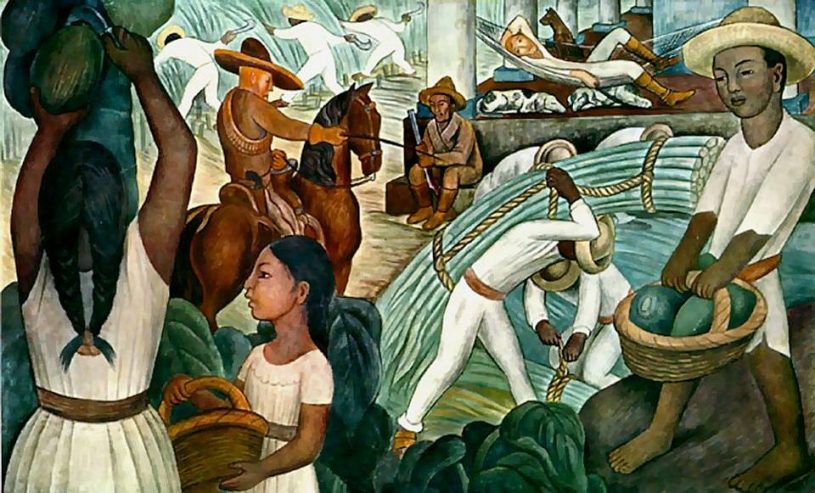

The crowd watched a video celebrating my grandparents. It focused mostly on the collection of Latin American art that they had recently pledged to a museum. We heard them share about their journey into collecting, their resonance with artists, and their love for each other as the video took us around a home populated by pieces from artists like Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Wilfredo Lam.

When I looked away from the screen, I saw the catering team standing at the edges of the massive room, watching along with us; they were about 95 percent Latinx.

One of Diego Rivera’s paintings came up on the screen. Rivera was a communist whose work critiqued capitalism and the ruling class. He said that “the role of the artist is that of a foot soldier of the revolution.” A revolution to change the exact social-political-economic reality that we were all sitting in at that very moment.

The painful irony of the moment didn’t seem to escape much of the catering team. I saw sadness, horror, and confusion. I saw it trapped behind the reality that there was nowhere for it to be expressed, and that when the video ended, these folks would be clearing the plates.

I felt as resentful of capitalism as Rivera did. I longed to connect with the catering team because it seemed like they were seeing the same reality as me, but here I was, with five different silver forks in front of me.

I walked out of the room and got a drink. A few I think.

In some ways I’m always sitting at that table. Torn between worlds. Longing to belong. Always struggling to navigate all the things I inherited: the money, the karma, the love, the possibility, the heart, the values, the society, my place in it, all of it.

A few months ago I turned 30, which meant I received access to a trust that had been established in my name. It’s been passively invested in a fund indexed to the American economy, which includes companies like Amazon, Exxon, and Lockheed Martin. Up until recently, I could avoid really looking at all this. It was out of my power to change. But now it isn’t.

Part of me wants to give it all away. The other part is afraid. I know that this economic system we live in doesn’t take care of those without money, so I am afraid to release my position. But the more folks are afraid to release our positions, the more the system continues to exploit and destroy.

Right now, I’m just trying to lean in deeper, and more authentically. I’m using some of the money to sustain me as I work in solidarity so I can focus on the impact of my actions, as opposed to whether I will be able to make money from them in the short term. Trying to be generous with the loved ones close to me, while also desegregating who’s close to me. I’m learning more about exactly what options are out there for me to move the money into economies that are aligned with my values. And I’m feeling into how I can leverage the fact I have access to spaces of money and privilege to help reorganize wealth far beyond the modest sum over which I have direct agency.

I’m scared to share all this. I’m afraid of how it will change how you see me and relate to me—especially the folks that I’ve been organizing in solidarity with for years. Will you see me as a whiny trust fund baby? Will you judge me for how I’m approaching my situation? Will you stop seeing the value of my heart, mind, and contributions, and only see me as someone who could give money? Will you avoid what comes up inside you when you hear this story and avoid me? Will you be afraid of giving me feedback and slowly disconnect? Will you give harsh feedback that doesn’t hold me in the dignity of my messy process of learning to be human? Will folks who might otherwise want to work with me not want to engage or trust me because of my class-position?

I know the stories I’ve told myself about people with money. The judgments I’ve placed on them in order to cope with my own unresolved feelings. I assume people will project some of those things on me; and some of the criticisms will be right. But I’m choosing to stop hiding this part of myself. Praying that I will be received for the love and integrity I am trying to bring to the path I’ve been given.

The reason I’m writing this is pretty simple: I know I am not alone.

I know there is a growing movement of folks with access to wealth that are feeling these things and asking these questions. There is a growing movement from folks who don’t have the same access to money asking those of us that do to get real and show up for the urgencies of our times. And one of the reasons folks with wealth are not responding to the full extent of our power and love is that we are trapped in old patterns that we are reluctant to speak openly about.

We fear not having enough. We fear rejection and exclusion. We fear being manipulated. We feel guilt and shame. The simple fact we have wealth shaped the contours of our experience, which in turn shapes to whom and how we connect, as well as what we believe. And we’ve got all kinds of feelings about that, too.

The deepest irony is that many of us fear that if we start talking about all this openly, we will be rejected and judged by the folks of other classes that we long to connect with, and this fear causes us to collapse, hide, and participate in the very behaviors that we are being called upon to transcend.

It’s a rat’s nest of potential energy. Hiding from it is letting it fester and become toxic to our bodies and our global community. These patterns of thought, feeling, and relating have been inculcated in us for generations, reinforced by our society, preying on our fears and traumas, and they will not unwind themselves unless we welcome them into the light and invite them to transform. And we can’t wait until if feels all safe and warm and fuzzy. Yes, we need to tend to ourselves and our vulnerabilities, but we also need to show up. Now. And if there isn’t a place where we feel safe exploring and unwinding this stuff, then we need to make one.

We may feel fear. But without fear there is no such thing as courage.

We may not know. But without the unknown, nothing new can emerge.

Simon, thank-you for being brave and sharing your experience and conflicts with privilege. I found many things in your article that feel uncomfortable and true but also very hopeful. Examining the types of privilege we enjoy ( financial, intellectual, geographical, societal, situational etc) is an important step in breaking through its qualities of separation and distinction.

This is refreshingly well articulated and openhearted, Thank you for sharing. I feel a familiar resonance with much of what you share, and am curious to learn more about you guys and the perspectives you’re bringing to the table here. I’m connecting with Andrew next Monday, and after reading this, I’d be curious to connect with you also.