Paraphilanthropy | Giving Money its Freedom Papers

featured photo | Photo by Miltiadis Fragkidis

A sea-change sweeps across philanthropic landscapes today. Critics of philanthropy, especially in its newer iterations of philanthrocapitalism, consider its colonial legacies, its deleterious effects on minorities, and the reinforcement of a politics of domination. As a result of these new perspectives, philanthropists and funders are now forced to re-evaluate their operations. In this article, I suggest that “spending-out” as a gesture of divestiture, as a way of responding to the challenges thrown by critiques of philanthrocapitalism, may not address what feels novel about emerging counter-capitalist concerns. More central to this piece is the idea that philanthrocapitalist critiques, by drawing attention to the exclusivist tendencies of industrial giving, seem to leave us within the troubling orbit of inclusivity – a dynamic that reinforces white modernity’s hold as the baseline reality. I suggest – with the coinage ‘paraphilanthropy’, that decolonial gestures need fugitivity, a longing for the non-legible, and support for social experimentation within undercultures of practice.

The counterfeit coin

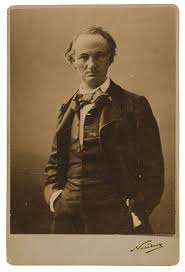

When the French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote “La Fausse Monnaie” or “Counterfeit Money” in 1869, a prose poem one might read as an exploration of the hidden undercurrents of charity, a vast enterprise of philanthropic gestures – led by the fabulously wealthy likes of Rockefeller and Carnegie – was only just beginning to entrench itself as a critical component of a world-summoning project, the aesthetic Baudelaire himself would name “modernity.” Baudelaire’s misgivings about the nature of giving seem to speak eloquently even now.

In Counterfeit Money, the narrator and his friend meet a poor beggar on the street. They both reach for their pockets, but the friend issues his coin first. Moments later, the narrator finds out his companion had given the unfortunate soul a counterfeit coin. What’s worse? He declares his deed proudly and seems to enjoy the fact of his deviousness, as an errant god might relish the thought of what might happen if he introduced a tempting snake into his otherwise perfect garden of innocence.

How the fake coin travels through the economy to which it has been introduced, we never come to know. This is neither Baudelaire’s concern nor the narrative voice the author deploys to service this short meditation on the nature of charity. The narrator turns away from the cartography of the coin and towards his friend’s charitable inclinations. “I saw clearly,” he concludes, “that his aim had been to do a good deed while at the same time making a good deal; to earn forty cents and the heart of God; to win paradise economically; in short, to pick up gratis, the certificate of a charitable man.” To win paradise economically.

By turning to the source of charity, the motions of candor and playful deception, Baudelaire’s narrator suggests that charity is more convoluted than one might first suspect. More ‘interested’ and animated than the epithet of benevolence often imposed on the act of giving. In some sense, the idea of a ‘fake coin’ carries with it a double charge: the coin is fake because it isn’t an acceptable means of exchange in the narrator’s universe. But it is also ‘fake’ because it is a Trojan Horse of some kind, carrying within its metallic core the threads of something more eventful than mere compassion. The coin is “counterfeit” because it comes with something else; it is not pure, innocent, and value neutral. There are calculations here, negotiations on different orders of scale.

The problem with giving

Giving has never happened in a vacuum. Giving creates worlds, depends on worlds, and reinforces worlds. Giving is an aesthetic of a moral order at work.

I grew up in southwest Nigeria, in Lagos, where almost every street had a church. My family never missed church. Sundays were sacrosanct, as were Thursdays and some Wednesdays and other arbitrarily announced “mid-week services” that fed the congregation’s longing for belonging.

Like ants secreting pheromonic trails, each church emitted and maintained a firmament, a paradigm of ceaseless giving, in which every devout parishioner was expected to “give unto the Lord” and to the Lord’s children. In this ecosystem of apparent benevolence, there were unwritten rules. They occasionally became explicit in sermons and everyday conversations, but they mostly stayed hidden, exerting their microbial influences from their invisibility.

The rule? One must sow one’s seeds on fertile ground. “Fertile ground” was code for giving so that one pleased the Lord – where pleasing the Lord was often a substitute phrasing for reaping bountifully from the surplus value of one’s investments. It was less about the recipient’s needs and more about the speculative potential each investment had. We were charitable like Baudelaire’s devious protagonist, calculating in our candour, issuing fake coins that may have landed on the palms and in the pockets of the less deserving but didn’t stay long there – since they had other directives to fulfill.

I remembered my early ecclesiastical introduction to charity when I read a fairly recent Al Jazeera report on the troubling politics of charity and philanthropy in the world today:

In the name of “charity”, the Jewish National Fund of Israel is buying up Palestinian land in the West Bank for colonial settlements and calling it “environmentalism”; far-right Hindu nationalist organisations are propagating their fascist-inspired ideology across the world and calling it “decolonisation” and “anti-racism”; and monks who justify genocide in Myanmar are running tax-exempt centres across the United States for the practice of “religion for peace” Buddhism.

The essayist critiques “the empire of charity” in the ways it serves to enforce “deeply-rooted structures of domination. The difference is that the non-profit version operates under the mantle of benevolence and love – ‘love’ being the literal translation of the Latin term caritas, from which the word ‘charity’ is derived.”

So it is no surprise that the motivations and operations of traditional philanthropy are increasingly called into question as their entanglements with troubling colonial dynamics, extractivist sources of wealth, algorithmic pathways that perpetuate a marginalization and displacement of minorities, a dependence on sources of knowledge that have little to do with the lived experiences and concerns of “aid recipients”, and the erasure of democratic procedure in the adoption of artificial intelligence measures, are becoming clearer.

In the last example, recent advancements in technology have deepened the intersections between philanthropy and artificial intelligence – with troubling implications. While it might be true, as the Dorothy Johnson Center for Philanthropy writes, that “cost-effective and user-friendly artificial intelligence tools support grant writing, fundraising, and other key areas of philanthropic work”, what is lost in this affirmation is not only the observation about the exclusionary dynamics of “user-friendliness”, but – perhaps more critically – how the tools we fashion, make us in return.

It seems blissfully naïve to suggest that artificial intelligence would merely improve philanthropic work without also noticing how it changes philanthropy – often by fortifying inherent tensions and painful invisibilizations in the charity world.

In short, without reducing philanthropy to a monolith, or treating it as an “evil” to be expunged, it seems to me that philanthropic solidarity constitutes a form of biopolitical control, an extension of biopower, a disciplinary regime that governs behavior, marking life in a civilizing sweep – naming what counts as knowledge, naming what counts as action, naming what counts as agency, and naming what counts as accountability. In its work of naming the world, it resources a moral field, reinforcing the parameters of a public order that now seem to be critically incapable of holding up the ontological weight of white modernity.

There’s more.

Because Foucault’s articulation of biopower – a reference to how power governs life in the absence of traditional nodes of sovereignty – seems to need the added complexity of Mbembe’s necropolitics (wherein the Cameroonian philosopher admits that the biopolitical management of life works side-by-side with the administration of death to bodies deemed discardable), one might even say that despite the apparentness of philanthropic benevolence, there is poison in the pot.

One need not produce villainous accounts of reptilian billionaires hiding behind the scenes, twisting the world to their images, to notice the ways traditional philanthropy can help maintain problematic worlds.

The crux of the matter is that money tends towards where it might reproduce itself. Its choreography is surplus value. The plantation directs the erotic flow of money and moves it towards the preservation of particular ways of knowing the world, particular modes of producing knowledge, and particular accounts of what social change means and for whom it is meant.

Decolonizing philanthropy?

From Vandana Shiva’s critique of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, highlighting the billionaire’s outsized role in determining the shape of policy and the shape of seeds (while leaving out democratic participation), to Edgar Villanueva’s insistence that “philanthropy has consistently and systematically left out people of color, even when a lot of times these are the exact people it intends to help”, a broad-based critique of the ways giving is performed – especially the ways that it preserves colonial relations – is becoming more influential.

When the Lankelly Chase Foundation, a charitable grant-making organization with more than 60 years to its belt and 130 million pounds in assets, announced in July last year its plans to wholly redistribute its assets and shut down its operations within five years, its announcement sparked debate in the industry. The trustees of the Foundation wrote that they could “no longer reconcile our position as an owner and active accumulator of private financial capital with a mission anchored in social, and particularly racial, justice and equity.” A few days later, the Albert Hunt Trust said it would spend the remainder of its 50 million pounds by 2029 and mark its 50th anniversary by closing.

It would seem there’s something in the air: Lankelly Chase’s and Albert Hunt’s decisions to spend out feel less like isolated gestures and more like a quality of a political moment. The intelligence of the hour. Perhaps connected to larger political projects. Some commentators even suggest their closure is the right step forward in addressing the inequity of wealth accumulation and the legacies of colonial theft.

The decision of these organizations to adopt abolition, to spend out and redistribute their assets, comes on the heels of attempts to decolonize philanthropy, given its colonial legacies.

But what does it mean to decolonize philanthropy, and is self-closure an instance of this quest for decoloniality?

Some of the more significant critiques of traditional philanthropy maintain that the need for decolonizing philanthropy emerges from readings of the patterns of exclusion that populate industrial charity spaces. For instance, a recent report on diversity, equity, and inclusion in philanthropy, shows that 91.6 percent of CEOs and Presidents of foundations in the United States are Caucasian, while less than 10 percent of philanthropic leaders are of African American, Latino, and American Indian descent. Given the almost totalizing racial homogenization of philanthropy, it is no surprise that decoloniality is consistently framed as the quest for radical inclusion and representation in charity, as increased agency in decision-making for minorities, and as accounting for the role of trauma in perpetuating a white overculture. It would seem like this quest for accountability is, to some degree, being translated as divestiture, as abolition, as ‘spending out’. Decoloniality – tied to these indices – would be a gesturing for an ‘outside space’, pristine and purged, free from the contradictions that make colonial capitalism and philanthropy an odd pair.

While inclusion, equity, and diversity (DEI) are highly important dynamics and worthy goals, an analysis of decoloniality that turns on these measures may risk obscuring the violence of inclusion. Inclusion into what? Firstly, if inclusivity (used here interchangeably with inclusion) is about deepening minority representation in decision-making, and promoting justice and fairness in institutions, it would seem like a non-controversial value to celebrate and push for. However, even with the illustriousness of those very parameters, inclusivity can work side-by-side with an overculture to maintain troubling relations. It often works on the modern pretext that there is one world to be included into – a baseline reality for which ‘access’ must be fought. As such, the discourse around inclusivity and access often leave out the ‘violent’ ways bodies are forced to fit in, what is left out in doing so, and how eventual belonging is always a negotiating away of potentially emancipatory materials.

For instance, even when an organization has decision-making members with diverse backgrounds and perspectives, the kinds of problems and challenges that demand an executive ‘decision’ (and the ingredients available to work with) often necessitate a homogenization of approaches, exerting pressure upon a group to act in ways that preserve certain outcomes.

Diversity is often then a distraction from the ways that bodies bleed away from their normative identities and designations to constitute, in part, gravitational fields of repetition and reinforcement.

One might argue that inclusion is just one aspect of an equation that also requires equity for the manifestation of just worlds. But giving people what they need to succeed in a fair and equitable way doesn’t quite address the racializing effects of what they now need to be succeeding at.

It feels important to point out that white coloniality, articulated here as the worlding practices that mark out bodies as either adhering to normative standards or falling below them, thus constituting a racialized instrumentalization of bodies and lifeworlds, perceptual habits, and persistent values, doesn’t seem to be scandalized by diversity, equity, and inclusion. Indeed, the metric of DEI is responsible for billions of dollars in mobilized funds within troubling capitalist relations and giant organizations. In short, what often passes as decoloniality is a deepening of white coloniality.

A lot of “decolonial critiques” of philanthropy misplace an attention to the ways white coloniality is normatively sustained, so that even when there is a call to decolonize philanthropy, the ensuing practices often leave philanthropy within modalities of responsiveness that leave the critical problems unaddressed.

When critique turns on increasing minoritarian participation, decoloniality may look like representation. When critique turns on calling out troubling imbrications with white colonial legacies, decoloniality looks like abolition, self-cancellation, and/or spending out. Representation, while needed, is still representation within settlement and baseline realities performed by colonial orders.

Philanthropic solidarity can reinforce a dominant system

What might decoloniality address then? How do we heed the potency of the problem at the heart of the invitation of decoloniality? What might decolonizing philanthropy look like?

Thinking about decoloniality invites traveling through the scholarly and forceful contributions of Black, Indigenous, and posthumanist thinkers over generations. One lineage of thought that speaks eloquently with me is the tradition of noticing the Human as a terrain, a topos, a colonial order rife with socio-political tensions about who gets to be named as fully belonging and those Others who are, by implication of not fully belonging, not-quite-human.

From the observations of Sylvia Wynter about the dominance of “the Man” to the explorations of Erin Manning about neurotypicality, there is a sense that the Human is not a fait accompli, not a finished product. Instead, it is a dynamic and racialized production and disciplining of bodies and subjects into varying modes of existence.

Whiteness is the material of this production, the logic of capture. It works alongside neoliberal humanism and alongside capitalist modes of extraction, perpetuating itself via a neurotypicality – a system of value that measures out what it means to be properly embodied, what it means to be a self, and – by extension – what it means to be dispensable. Neurotypicality is a domain of labor, a plantation that forces us to act in ways that increase predetermined definitions of value.

It’s difficult to sense it within its obviousness because most of us have been habituated into it. It’s how we practice being good bodies, the hidden curriculum of whispered molecular instructions that tell us how to navigate the tensions of modernity successfully: speak up to be noticed; regulate yourself while in public; give a firm handshake to be appreciated as strong and principled; get a degree; get a job; measure your laughter while in public so people don’t think you’re crazy.

In its exertions, neurotypicality regulates life and dishes out death and disappearance. Those good bodies stand a likelier chance of “making it”, and the others that can’t regulate themselves are either rehabilitated to enhance their access to the architecture of typicality or allowed to die. When neurotypicality meets state power, it becomes Foucault’s biopolitics – but not just that: it also becomes Mbembe’s necropolitics. A kind of state decisionism that manages populations by killing the Others – softly.

What feels provocatively interesting to note is that this territory of necropolitical neurotypicality, this plantation of the Human, often disseminates its call to labor in the guise of justice advocacy, in its proposals for healing, in its invitations to include more of the population in its gilded space of typicality or at least allow for increased representation. It will resemble a neoliberal progressivism, championing diversity, inclusion, and equity – so long as its internal logic of maintaining ‘good bodies’ remains true and fast.

As such, it is my sense of things that the plantation exerts a kind of moral power, an iatropower (where iatropower is how I designate the supplementary forces that propose aid, justice, healing, and belonging to the disgruntled and disaffected aspects of the population – so long as those modalities keep them within its orbit of surveillance and management).

One might sense an iatropolitics in the discourses that urge minoritarian populations to speak truth to power by becoming woke, to migrate to the center where power lives, to seek greater representation. None of this is ‘bad’ or ‘good’ – but it risks reinforcing coloniality.

***

Money is a how, not a what. It is not a thing; it is a mode of relations. A practice. A practice that precedes and exceeds the ‘thing’ we identify as ‘money’. An ecology of anxieties, rituals, modes of accountability. Desire captured in the labors of the plantation.

It is possible to think of the neurotypicality of money, naming the curatorial efforts to divert desire in its choreographical flows towards the furnishing of good bodies.

In its deployment within an iatro-necropolis (or normopathy) of neurotypical regulation.

It seems to me that critically addressing philanthropy is questioning our place in this world of production, our roles in holding aloft the white colonial order that seeks to create proper bodies.

To the extent that mainstream critiques of philanthrocapitalism name these dynamics, they hold open the possibility for philanthropy – mired as it is in its colonial tensions – to become emancipatory. But it is more often the case that critiques stop at calling for more representation within the plantation-settlement. More diversity. More opportunities.

A lot of what passes as decoloniality thrives on self-purification or self-annihilation. This is because an aspect of the political spectrum truly senses that (in the words of Audre Lorde) “the master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house”. What it loses sight of is (in the words of Karen Barad) that the master’s tools do not stay faithful to the master for too long.

The motivations and gestures in the major discourses about decoloniality are questing for an ‘outside’, a site of purity from which to regulate the world, a place where our imbrications with agonistic tensions and troubling fields of reproduction can be sliced off – leaving us good and ready. But there is no such place. And the seeking of such a place may betray the hidden workings of iatropower. Of curdled whiteness revising its regulatory reach.

***

Decolonizing philanthropy may be practiced as increasing mobility within troubling moral orders, or it can be a way of staying with the trouble of these tensions, of acknowledging that there is perhaps nothing we can do on our own, by ourselves, to upset the logic of whiteness, and sniffing out the cracks in the bubble of neurotypicality.

I don’t think decolonizing philanthropy is a state to reach, a status to achieve. One must be careful about benchmarking it. About standardizing the guarantees and objectives. Instead, I think of decolonizing philanthropy as playing with its tensions, a site convened to the co-inquiry of how new worlds might come to be.

Money is research. Before it is frozen into profit or usefulness, the instrumental forms of typicality that proves useful to the labors of coloniality, ‘money’ names a dynamicity of seeking and experimenting and turning over and risking being bruised, at least when it is seen through autistic perception (a term Erin Manning uses to name an experimental, never fully resolved, way of touching life beyond neurotypical systems).

If money behaves neurotypically within whiteness, perhaps there is a way to encourage its neurodivergence – a way to release it from being a good worker, a good body. This release would be what I think of as decolonizing philanthropy.

Paraphilanthropy

Decolonizing philanthropy is coming to the edges of its usefulness. When usefulness is secreted by the plantation, decoloniality must be the pragmatics of the useless (cue Manning). A lingering at the edges of philanthropy, at the edges of neurotypicality. A dwelling at the sides where the potential for money to behave autistically, onto-fugitively, is dramatically hosted. A para-philanthropy.

I believe there is a way for money to move sideways, like a crustacean, not forward along the dominant tracks that have been laid out for it. How this happens is always a problem – without built-in fixes. This is why I invite a paraphilanthropy to emerge.

Paraphilanthropy is the recognition that even if equity were achieved, even if poverty were finally alleviated, and all these similar concerns met, the moral order’s iatro-necro-power makes it such that it won’t meet our expectations.

Paraphilanthropy notes that the Human colonial order, the terrain of whiteness, is in crisis. White stability is hollowing out. It recognizes there’s a need for new materialities of care, beyond the framework of proper bodies. This framework is stressed; it is losing its buoyancy.

Paraphilanthropy is the recognition that money doesn’t exclusively flow forward; it behaves awkwardly. It does other things that may not work in the vortices of surplus value and profit. It fails. Prior to its disciplining in grid-like bureaucracies of excel sheets, reports, and military-like deployment, it tends towards the minor; it swims in syncopated waters.

Paraphilanthropy is not a goal but a space of co-inquiry about our imbrications within knowledge systems and accountability modalities that preserve colonial orders. It is a festival on a slave ship. It is autistic investment. It sidles the logic of surplus value. It undercuts the usefulness of the legible and leans into the fugitivity of the non-legible as a viable way to think new worlds.

I propose paraphilanthropy not as a set of fixed practices but as an inquiry dispersed across networks at the end of the world: an inquiry not domiciled in universities but across networks of experimentation, across ecologies of practice.

Paraphilanthropy is not a smoothening out of the creases of coloniality by acts of self-abolition. It is a living between the valley of the creases, tilling the soil there, and experimenting with embodiment. It is trying out new modes of being accountable. It is cultivating new kinds of abundance. It is playing with carnivalesque modes of research.

The work is about inviting networks to hold space to address and experiment with these posthuman tensions. An ongoing questing. A seeking together. A trying-things out. A listening-in.

Perhaps decolonizing philanthropy or, as I frame it, paraphilanthropy, can take the form of attending to the ways we are becoming-black (a term I deploy to note the ways whiteness is losing a hold of its subjects and has never had a totalizing control over them; in other words, this is how I name the emancipatory openings within white closure), where resources are directed towards not guarantees or resolutions but fields of experimentations and fugitive study.

A critical part of philanthropy will still need to be devoted to addressing the critiques articulated in the growing concerns about philanthrocapitalism. Of course, there is no doing away with living in settlement for now. Philanthropy as an ecology, a moral order is still concerned with anxieties about governance, best practices, power, equity, inclusion, diversity. Minorities indeed need to survive; representation does matter. And inclusion, while fraught with risks, can open up to new practices that prove emancipatory and transformative.

However, if we were to leave it here, if we were to centralize the public good, we risk reinforcing neurotypical values. If we were to stick exclusively to dominant critiques of philanthrocapitalism, we risk returning to convergence patterns. We risk installing solar panels on slave ships or building nice sidewalks in the plantation – when the thing to do now, it seems, is to break away from the labor of neurotypicality.

Paraphilanthropy is process, not remedy. It offers a more robust framing than the critiques of philanthrocapitalism which often come already pre-formulated with ready answers. To address the logic of coloniality, it notes that world-generating resources need to be directed towards sites of rupture, towards carnival as research, to the work of post-democratic, post-human inquiry.

***

Can philanthropy become something different beyond the violence of its colonial origins? Not within the usual ontology of its perpetuity. One needs a para-ontology to respond to that question. Paraphilanthropy is a being in response to the questions of colonial imbrications. Paraphilanthropy is making sanctuary for the atypical in times of turbulence.

The year 2024 presents itself as a seminal year in the life of the white colonial order, simmering with threatening tensions and hidden movements. At surface level, this year is a test between democracy and fascism, between the left and the right, between conservativism and progressivism, between woke and not-woke, between death and life. Half of the world will be going to the polls. Half of that half will wonder why the other half chooses in the ways that it does, probably pathologizing the other as stupid, wicked, or critically unable to read the signs. What the surface chatter hides is that the citizen-subject is in crisis, and the framework of white belonging is exhausted in its maintenance of identity.

Beyond the anxiety-ridden sites of who to choose and how to choose, larger principalities and territories groan and rumble and toil, adjusting to contain the tensions. To meet expectations or parry them. Anything to keep the modes of subjectivization working along the lines of maintaining neurotypicality.

Whatever happens, whoever emerges to be the face of the next regimes of production, it seems likely that the plantation will emerge unscathed. Philanthropy can dedicate its tensions, its contradictions, its failures, its inquiry to the resourcing of underground, underculture, subterranean, paraterranean networks of experimental inquiry at the edges of the Human.

It will look like giving money its freedom papers.

A version of this article was originally written for the Christopher Reynolds Foundation in Massachusetts, Turtle Island.

Return to Kosmos Edition 24, Issue 3, Healing Wealth

FOOTNOTES

1 https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/3/12/for-love-charity-washing-colonialism-fascism-and-genocide