Vision for a City of Hope Near Auschwitz

From a quiet meadow in Cambodia to the twin fountains of Manhattan, humanity’s worst moments have left scars across our landscapes and our psyches. They appear in the shape of long concrete slabs in Kigali, Rwanda, or a crooked, skeletonized dome atop Hiroshima. Reminders of past tragedies, they remain in a constant state of slow and imperceptible healing throughout history.

The Holocaust is undoubtedly the largest and longest scar in modern Western history. You can trace it as one would trace a railroad track in a desolate field, leading, inevitably, through the brick archway of Auschwitz. Since liberation and the subsequent forming of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in 1947, the public has willingly entered such archways. Now a UN World Heritage site, an annual 2 million people from all walks of life across the world come to mourn, find names, to see and feel and know what was once the world’s darkest secret.

I first visited Auschwitz in 2015. This came at a time when I was slowing down Children of the Earth, a UN NGO that I founded and directed for over 30 years that worked and reached into 90 countries. Never did I imagine that I would have anything to do with Auschwitz.

I was invited there by a small group of women who were doing a project in Berlin based on their work in peace and sustainability. Walking through the camp, I came to the large Book of Names: a list of every murdered prisoner. Browsing through the list, I discovered not only my maternal grandmother’s name but 20 other family members who also had been murdered. During my life, I have traveled to various war-torn countries. I’ve encountered all manner of suffering and misery, but seeing these names haunted me to the core. I knew then that part of my legacy would need to include future projects to honor those 20 names (and millions of others), and also make a difference for the world’s future generations. After meeting Domen Kocevar, a social activist with a background in theology and sociology, I realized that Auschwitz was the impact point for the final landing site that fused all of my previous work. It was then that Domen fostered the idea of One Humanity.

Science and spirituality have come to the same conclusion: all people are intrinsically similar; the human genome project has proven that we are genetically 99.9 percent alike, with only one tenth of one percent that makes us different. When we realize that “I am you and you are me,” only then will right action and thought be supported by the universal laws of nature. When we can concentrate on what makes us the same instead of what makes us different, only then can we deal with the challenges ahead. The overarching goal for this vision is to lay the groundwork for global solidarity that gives rise to what it means to be One Humanity.

There needs to be a housing for all of these ideas, something concrete and anchored in the real world. A physical place that manifests the theoretical, where ideas become actions. The need is clear for a One Humanity Institute.

The One Humanity Institute (OHI) is a nonprofit charitable foundation co-founded in 2017 by me and Domen. It embraces peace that goes beyond the mere absence of conflict and war, to bring about a change of heart that embraces our common humanity. Peace in this sense is a dynamic concept that facilitates the full development of the human potential. Our intention is to create a transformative campus for mutual cultural understanding next to Auschwitz, named “City of Hope,” which provides a visionary, experiential, and tangible place to actualize this vision.

City of Hope will offer structured learning opportunities in a variety of forms for all ages, through both formal and non-formal education. Such opportunities will focus on the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals, conflict resolution, responsible stewardship of our planet, and the promotion of religious and spiritual pluralism. By promoting new methods of governance, innovative finance, and transformative education systems, OHI aspires to encourage a new narrative for humanity that not only honors the sacredness of every human, but proposes new approaches and new systems to nurture this into reality.

The size and scope of the project have expanded remarkably from its humble beginning: a park bench. Domen and I first wanted to address the need at Auschwitz for a quiet place of reflection after touring the camp—a space that could allow the impact of Auschwitz to become a lesson in itself for needing change. Then we considered the idea of a student exchange program with a local school as an avenue of furthering multicultural and interreligious understanding. These small projects only fed our desire to expand the concept of OHI, and as our aspirations grew, so did the roadblocks in our way. But as one door closed, another opened.

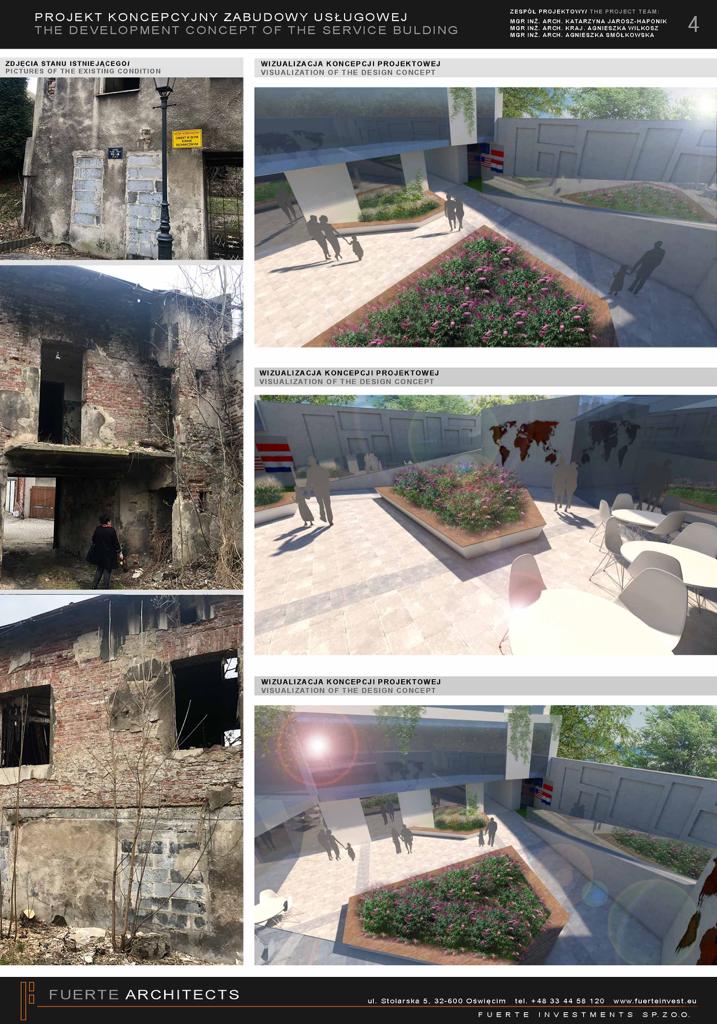

The project, as it stands today, was made possible by one fateful, fortuitous event—the day we learned about the 11 unused barracks adjacent to the Auschwitz Museum. These structures originally were occupied by the German army during the war. Now they sit dormant. Our plan is to purchase the land that houses these barracks, then transform the unique and symbolic space into a City of Hope. The area will contain an NGO hub, library, EnVisionarium, learning and research center, peace gardens, and hotel.

The EnVisionarium is an interactive, innovative museum of the future, designed to integrate the understanding of sustainability with that of human connectedness. Visitors will be exposed to revolving exhibits, innovative experiences, and living, experiential structures for mind-shifting. Guests will access practical tools: innovative, state-of-the-art, and virtual models that provide breakthroughs for resolving both personal and global issues.

The OHI Learning and Research Center provides transformative learning programs and experiences in peace and sustainability for all ages that foster a structural shift in human interconnectedness. It will involve a global community of scholars and practitioners from diverse backgrounds to address urgent social, political, and ecological problems. With official ties to renowned universities around the world, the Center will host courses, global youth exchanges, workshops, training programs, think tank meetings, and more. The Center also will contain a digital Peace Library.

The OHI Hub focuses on a number of issues, including entrepreneurship, social innovations, and 21st-century technology, particularly for youth. By providing shared offices and working space for NGOs, the OHI Hub will provide an environment for unprecedented, unified, and collective impact. The Hub also will offer space to organizations that share common values as a means to cross-pollinate skills and expertise.

Upon the advice of numerous well-informed Polish citizens and leaders, we made an investigative trip to Israel to learn more about its perspective. While there, we met a second-generation Jewish survivor whose family had lived in their bakery in the old city center in Oswiecim. He has donated his family home to OHI in order to connect the past with the present, and to create a better future. This building, once renovated, will be our headquarters and a pilot prototype. Not only will the home serve as a bakery as it did 80 years ago, but it will provide co-working space for youth and other social innovators, local organizations similar to OHI, and volunteers. It will be known as Bakery2030 (Piekarnia2030), a reference to the year on which the UN Sustainable Development Goals are to be accomplished.

Since 2015, Domen and I have had many visits to the town of Oswiecim, as well as meetings with the town governor, mayor of the city, and representatives of local NGOs and educational institutions. We also have engaged 40 experts to work with us—a diverse group of thought-leaders, change agents, and individuals from across the globe with vast experience and broad backgrounds. We currently are forming a global Youth Council of formidable young leaders.

By learning from the lessons of the past, we can create bridges to a future of One Humanity values. After five years of this work, I realize the enormity of the OHI vision and undertaking. The present world needs a recalibration to create a better future. It is now necessary for our survival as a species to go beyond personal greed and the false separation of identities fostered by religions, genders, cultures, and ethnic groups. Our lives are hanging on a shoestring, floundering. Many from the generations to follow already recognize these ills. They need us to be a bridge in order to understand that we must experience ourselves as one humanity. Only together can we resolve the global issues we face. We are walking into a state of emergency where “Never Again” seems distant in the past, yet more than ever we need this phrase as an essential reminder. OHI is more than a project; it is a call to make visible the possibilities of how we may live together in a positive manner that serves humanity as a whole.

The time has come for us to commit to stewarding a better future—one that works for everyone. A world of One Humanity. We have bold goals for OHI, indeed, but the feedback we are getting across the globe tells us that our idea is one whose time has come.

Re-member Humanity.

Beautiful written Nina and Domen. Thank you for sharing.