Making Politics Sacred Again

Many Americans are currently suffering from an all-consuming addiction to politics. The media, happy to feed this obsession, announces breaking news at every opportunity, often pushing it directly to our electronic devices (to which people are also addicted). Information overload is a legitimate public health concern—and that is only half the story. We are also addicted to conflict and division, fueled by a two-party system and the bifurcation of information into liberal or conservative news outlets. The last time the country was this divided was during the 1850s when Democrats read one newspaper and Republicans another—and we know how that turned out. A similar schism again threatens our nation.

The founding fathers warned us of times like these. Intent on presenting a unified front to the world, they discouraged factions and political parties. I, therefore, characterize the birth of the nation as a form of Unitive Consciousness, even if it was not the most evolved nor long-lasting form.

It is true that divisions quickly arose, such as the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, but it would be a mistake to consider these the equivalent of modern political parties. The modern two-party system took nearly a century to evolve.

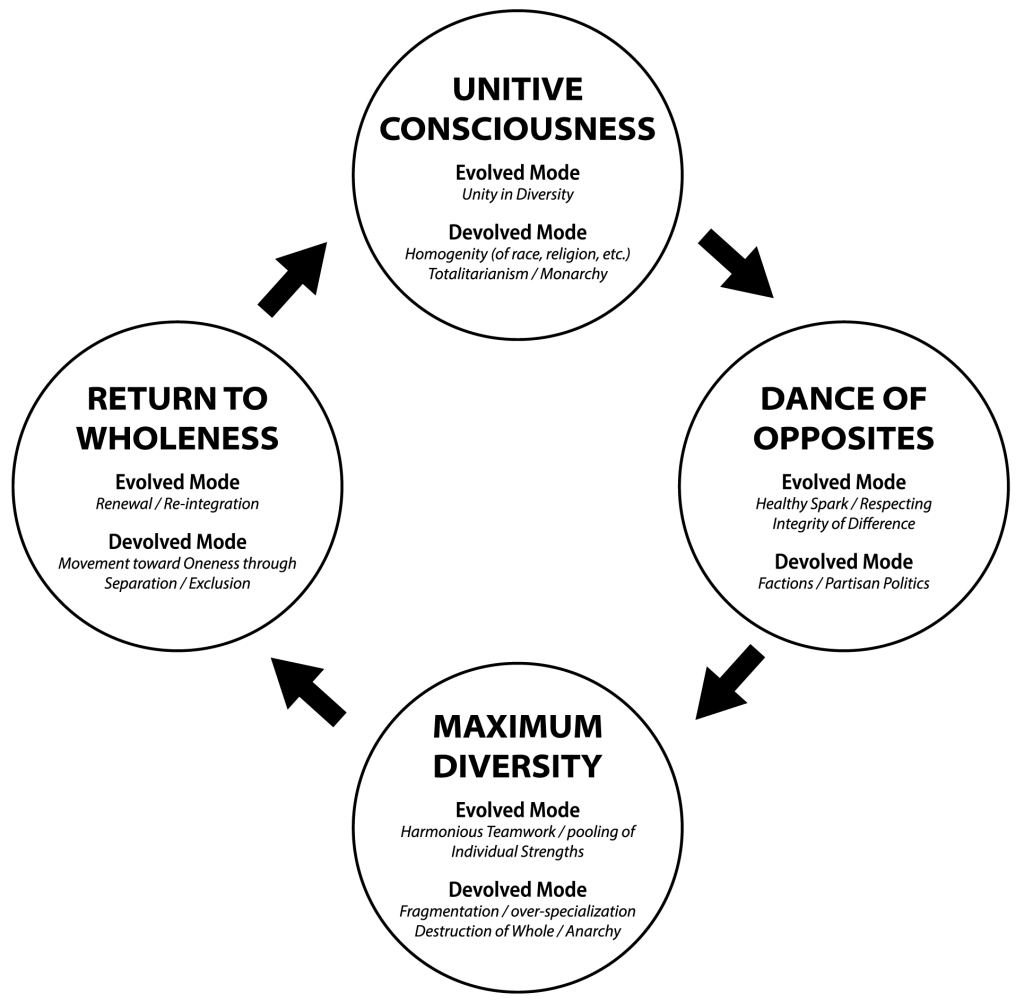

At its best, the party system is an elegant dance, tango partners playing off each other. At its worst, the system becomes stuck, its wheels in the mud. The wheels of politics: dialogue, compromise, and bipartisanship, are not just stuck today; they are decaying from disuse. Common ground must be found, and soon, if we are to end polarization. The desire for unity, however, has both evolved and devolved modes, as the below diagram depicts within the context of evolving consciousness within the United States.

The top circle of the diagram represents the birth of the nation; the second, the birth of the two parties; and the third, where we are today. To some degree, we are also in the fourth circle, as we are beginning to seek wholeness, either by a renewal process or by oneness through exclusion and separation. Each step along the way has both an evolved and a devolved mode. What I call devolved is, in truth, an integral part of the process, because things tend to change and evolve only when they have already deteriorated so much that a new way of thinking is demanded. For example, the colonists rebelled against England only after the colonial relationship had broken down, giving the nascent country an opportunity to establish its own identity apart from the mother country. The change from a monarchy to a representational republic was dramatic, but like all life born from mothers, something of the original bond was retained. Although natural, this can become another form of addiction.

From the beginning, the nation has been caught between the evolved and devolved modes of Unitive Consciousness: between monarchy or liberty and justice for all. Despite the flowery rhetoric of all men being created equal, our initial step toward equality was a baby step, restricting equal voting power to white, male property owners. Clearly, the founders carried over European concepts of class and property; they also retained British common law regarding the subservience of women in the household. There was initially no role whatsoever for women in the political process, nor was there a place for people of color. To their credit, the founders added the potent phrase “to form a more perfect union” to the Constitution, implying changes yet to come. And change has come. Despite the sordid century-plus history of Indian Wars and periodic retreats into white nationalism, the overall arc of the country’s history has been toward unity in diversity, the more evolved mode.

The evolution of consciousness has unfolded in America the way Taoist sage Lao Tzu understood all things to unfold: from the one, to the two, to the many things, with the Tao (oneness) driving the process all along. It was inevitable that duality would emerge in the political parties; it was also inevitable that an increasing diversity and fragmentation would occur, stimulating a desire to return to wholeness. If we recognize what is unfolding, we can facilitate change in a harmonious manner. If we do not, we will still change, but only through radical disruption, as is now occurring.

The only constant is change. The political parties want us to believe they represent a fixed ideology, but nothing could be further from the truth. The parties pretend to be separate and distinct so that they can be marketed that way, inspiring loyalty to their brand. This is something that has been done intentionally, if somewhat disingenuously. In truth, neither party has a fixed ideology, and both have changed enormously over time. The result—one hundred and fifty years after the Civil War—is that both parties now occupy completely opposite positions from where they started.1 The final do-si-do on the dance floor occurred in the 1960s, when more Republicans voted for civil rights legislation than Democrats. It was only then that the southern Democrats fled the party and became the base of today’s Republican party. Thus, the Republicans of today are remarkably similar to the Democrats of Lincoln’s time, and the Democrats are remarkably like the original Republicans. It is not a coincidence, therefore, that our political system is as polarized now as it was during the Civil War, and that the issue of race relations is cropping up again.

The Founding Father’s Attitude Toward Slavery

The way we are as a nation today has a lot to do with what the founding fathers could not reconcile within themselves, largely because their thinking was anchored (if not addicted) to past precedent. Nowhere was this more evident than in the founders’ inconsistent stance toward slavery. Many of the founders acknowledged that slavery violated the core principle of liberty as outlined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, yet many were slave owners, and of the nine presidents who owned slaves, only George Washington freed his. John Adams, who did not own slaves, said the revolution would not be complete until slavery was abolished. Thomas Jefferson called slavery a “moral depravity” and a “hideous blot,” but he himself enslaved more than 600 people over his lifetime.

Clearly, the founders’ ambiguity over slavery pushed it into the shadow of the nation’s consciousness. But suppressed wounds can fester only so long before erupting; it was the founders’ failure to deal with slavery that culminated in the pus and blood of the Civil War. More soldiers died in combat during the Civil War than during WWI, WWII, and the Korea and Vietnam wars combined. Yet, the Civil War did not resolve the conflict over race, partly due to Lincoln’s assassination, which stymied the post-war Reconstruction process. The root cause of the Civil War remained in the shadows; a much-needed national conversation over race never really materialized.

Recovery of Shadow Elements from American History

The United States might be well-advised to undertake a truth and reconciliation process comparable to what South Africa undertook after apartheid. We need to air our differences in a dialogic forum of mutual respect. We need restorative justice that heals, not blames.

Dialogue, when moderated correctly, has the capacity to make deep changes in how the mind works. The most important aspect of dialogue is listening—specifically, listening for the purpose of understanding rather than to ready a reply. When we listen deeply with our whole being, seeking not to discuss or debate but only to understand, we learn. This is how we readily learned as children, and this is what we must do again if we are to break the bonds of conditioning holding us captive to our addictions.

Dialogue is most effective when conducted in a circle, in part because circles are more than symbols; they embody full participation. There is no beginning or end to a circle and no hierarchy; every place is of equal importance and everyone contributes to the whole. Dialogue implicitly promotes harmonious communication and consensus building. Consensus is misunderstood by moderns to mean uniform agreement when, actually, it is unity in diversity, born of inclusion. A dialogue group is a creative hybrid space from which new information is collectively constructed. It leads to fresh, original thinking, in contrast to addictive thought patterns that keep us ruminating, going nowhere.

The origin of dialogue in America is from Native talking circles. Many of the founding fathers, including Franklin, Jefferson, Washington, and Paine, participated in Native American council meetings where they learned something about consensus building. We know that these dialogic, community building practices were freely incorporated into early American politics. The practice of informal, information-sharing meetings still exists; it is called caucusing. But few today realize that caucus is an Alquonquin word. The tradition of town halls also was adapted from Alquonquin (Naragansett tribes), and the Tammany Hall process of political organization was adapted from the Lenape (the name Tammany comes from the Lenape elder, Tamanend).

It is also true that the 19th-century women’s and abolitionist movements were inspired by observation of egalitarian Native American societies. Many Native societies had both women’s and men’s councils, and often the women’s councils were the wisdom councils that set the agenda for the men to enact. In the Iroquois Confederacy, it was the women’s council that nominated the male chief—and had the right to remove him if he acted inappropriately. We retained a vestige of that practice in articles of impeachment law, even as we initially excluded women from political participation.

A Collision of Worldviews

The political nation of the United States was born from a nearly three-century collision of worldviews between the European and Native American mind. Not all this interchange was negative; in fact, there was a wealth of positive interactions. It was once understood that America was a hybrid of Native American and European values.

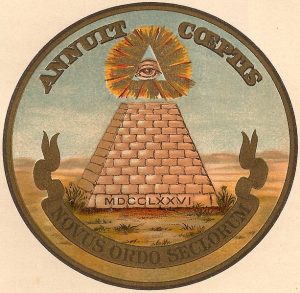

The United States of America was founded on a simple but profound idea: e pluribus unum (out of the many, one). From the divided states, we formed a union. The seed idea to unite—and the lofty ideals of liberty and equality—came from Native America, and particularly from the Onondaga Chief Canasstego of the Iroquois Confederacy, transmitted through Benjamin Franklin to other open-minded founders.2

What is Sacred Politics?

The idea of a sacred politics may seem like an oxymoron, but before the United States was born, politics was practiced in a sacred manner right here in the Americas. This does not mean there was no conflict or division in Native societies—there most assuredly was. However, Native peoples understood that harmony within human communities depended upon harmony with nature.

In contrast, Western politics separated human from nature in its very beginnings. The etymology of the word politics is from the Greek polis, meaning the city. Politics, as conceived by Aristotle, was a human-centered (and male-centered) urban affair. The more-than-human world of nature was not considered. And therein lies the seeds of our destruction if we do not change.

The separation of human from nature is an illusion. We cannot breathe without the trees that give out the breath of life (oxygen) that we give back to them (CO2). We are made up of the elements, wholly dependent upon their health for our survival. All the economic growth in the world would not mean anything if there were no longer nutritious food to eat or clean water to drink. We must protect the elements, for we are the elements. This is an inescapable fact.

Concluding Thoughts

It is not too late to give up our addiction to conflict and division. It is not too late to recognize that we are all in this together. When the Indian sage Ramana Maharshi was asked, “How should we treat others?” he replied without hesitation, “There are no others.” It is the same way with our relationship with Mother Earth. Every critter on Earth is related to us. There are no others. They are all our relations.

There is one addiction that I, for one, do not want to give up, and that is my addiction to Mother Earth. The root of the word addiction is the Latin addictus, meaning “to devote or give up (oneself) to a habit or occupation.” The past participle is addicere, which means “to deliver, award, or yield.” In seeking to predict and control nature, we have become addicted to power, conflict, and division; but we have, ironically, lost our addiction—our devotion— to Mother Earth. That is where we went wrong, and that is also the path forward.

We still have free will. We can use it to continue on the path of separation, of the devolution of our republic, or we can choose to make politics sacred again. We can choose to live in accord with Nature’s cyclic rhythms, realigning ourselves with the wisdom of Nature. That is the sacred way, the way of the Tao. That is the way of water, softly course correcting, steering around all obstacles, always flowing, never striving.

The highest good is like water.

Water gives life to the ten thousand things and does not strive.

It flows in places men reject and so is like the Tao.3

References

1. Heraclitus coined the word enantiodromia, or the principle that, in time, everything turns into its opposite, something that was later popularized by Carl Jung.

2. Chief Canassatego addressed a colonial assembly in Lancaster Pennsylvania on July 4th 1744 with these words (which were, not coincidentally, published by Franklin):

“Our wise forefathers established Union and Amity between the Five Nations. This has made us formidable; this has given us great Weight and Authority with our neighboring Nations. We are a powerful Confederacy; and by your observing the same methods our wise forefathers have taken, you will acquire such Strength and power. Therefore, whatever befalls you, never fall out with one another.” To amplify his spoken message, Chief Canasstego presented Franklin with the gift of a single arrow. While Franklin was examining it, the chief suddenly took back the arrow and broke it over his knee. Canasstego then reached behind him to pick up a sheaf of bundled arrows and again attempted to break them across his knee; but this time the arrows would not break because they were joined as one. He then ceremoniously presented the bundle to Franklin, and the meaning was plain to all. Franklin never forgot the import of this symbolic gesture, and years later, while serving as a committee member designing the Great Seal of the United States, he recommended that the symbol of the 13 bundled arrows be carried in the talon of the eagle. In Carl Van Doren and Julian P. Boys, Eds., (1938). Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin 1736-1762). Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1938, pg 75, italics added.

3. Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching. Translated by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English. 1997. New York, Vintage Books.