Looking Back | The Visionary Spirit of Resilience

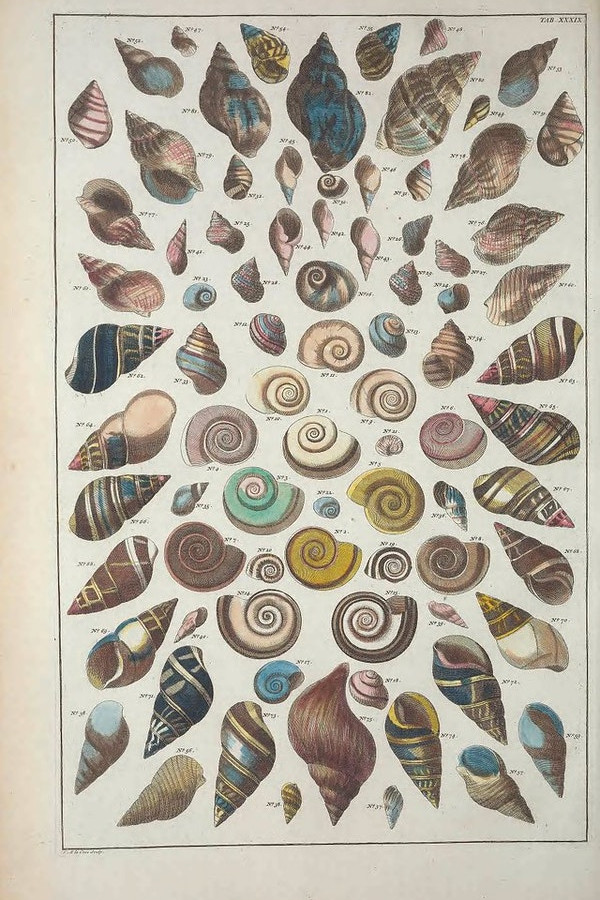

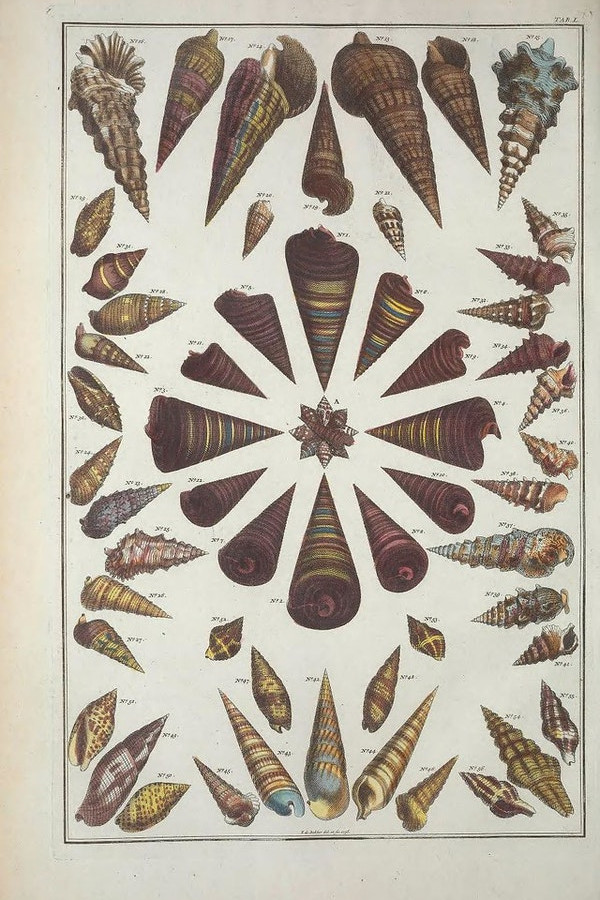

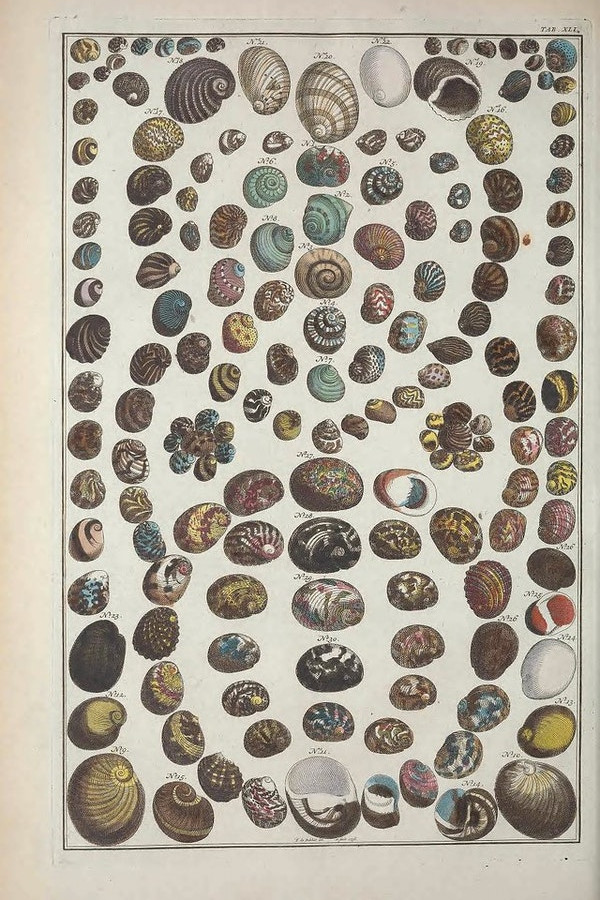

When I was a young girl, my family would go to South Carolina’s Litchfield Beach for a week-long summer vacation. I wasn’t a get-in-the-water kind of kid. My joys came from walking, barefoot, as far up and down the beach as parental permission would extend, sometimes a bit farther. I scanned ahead for favorite shells and sharks’ teeth. Dozens of these treasures have remained with me for decades; cherished belongings set in a glass case to which my front door opens. When my eyes fall upon them, I know that I am home.

I remember, on one especially blue-skied day, playing with the footprints that I’d left in the sand just seconds before, noticing how the impressions changed according to my stride and speed, the dampness of the substrate, and the force and stay of the waves coming and going across them. Instantaneously, the world works on the experiences we’ve had. Looking back, nothing can be as it actually was in the moment that it happened. There is addition (salty water), deletion (sand grains swallowed by the ocean), and distortion (shape-shifting form) in all of it.

“I don’t look back, only forward,” has become something of a prideful mantra in modern society. It’s as if there is some personal growth prize to be won through the act of annihilating our own tracks. I think not.

Thomas Hübl, an expert in processing collective trauma, wisely observes that “an integrated history is presence, and an unintegrated history is the past.” We see—backwards and forwards, right and wrong—with eyes informed by the bits and pieces that we pick up and claim as part of our integrated identity—sometimes consciously, sometimes at depth. The world, as we meet and experience it, is an amalgamation of the fragments that we and our ancestors chose to re-collect and hold on to.

But, not every ‘shell’ gets picked up. We don’t associate with them. We dissociate from them. Maybe they are too big, or too small. Maybe they are too broken, or chipped, or drab, or common. Maybe there is something squishy or clawed, scary or icky inhabiting them. For whatever reason, they are bypassed—maybe with regret, maybe not. We forget about them. They do not become part of our sense of identity, presence, or self-expression. We can’t put them to our ear to listen into other realms. We are not at home with them.

I left a lot behind in my childhood. In recent years, I’ve become particularly aware of deletions, absences of eventful memory, that—thank the gods and neural synapses—served to keep a traumatized child safe enough in her own skin. As an adult, I’ve started to look for these fragments, pick them up, and cherish them.

We stopped going to the beach after my father left. His decision to pursue an affair with his secretary drew an immutable line in the sand between my childhood and the child-adult that I had to become. It shattered the illusion of ‘family’ as a word to be equated with trust, security, and happiness. Waves crashed hard against the white, Protestant, middle-class semblance of familial perfection, of a normal home life, that I had been conditioned to accept and project into the world.

But, now that I can look back, there was more to the story—more to my story.

I knew. I knew from a very early age that my father’s attentions were not focused on my mother. Putting pieces together a few at a time over decades, I’ve rediscovered memories of a child confused by her father’s routine visits to other women, as well as the incongruous explanations, directives for silence, bribes, and threats that followed my innocence-grappling questions.

I knew. But, I was told that I was mistaken. I was led to believe that to seek clarity and align with the truth was an act of betrayal that could cost me and others in my family the benefit of the necessary illusion. My powers of observation, intuition, and discernment were invalidated. Parts of me had fragmented and receded. Unconsciously, I concluded that I couldn’t trust myself.

Thomas Hübl observes, “The one way to realign the intelligence of the process of splitting is to be willing to feel uncomfortable. We have to be willing to feel the discomfort of that which we excluded in the past. To realign, we have to feel uncomfortable.”

Shame is an intensely painful emotion frequently associated with traumatic memories. Early-life trauma may arise in a child’s voice saying things like, “If I’d only been better.” “If I’d only done ‘this’, then ‘that bad thing’ wouldn’t have happened.” In my case, well into adulthood, the child of me secretly felt a shame of complicity: “By not believing in and communicating what I sensed as true, I betrayed my mother.” Shame can drop us into wells of grief and launch us into fits of rage.

But, reflection—when cast in the light of self-worth and intent to understand without judgment—can draw bright, shiny objects to the surface. The beachcomber of me is a trustee of healing. She keeps her favorite sand bucket ready so that I can bring home precious things. As an adult, I’ve learned, step by step, that claiming these small beauties as my own enables me to honor my truth and standby it even if the act of doing so feels risky—sometimes, like it could cost me everything. There is no shame in that.

As a society, as a species, I think this is where we are at: this place of—in the sands of time—needing to consciously look back and observe the marks that have been made, our impressions on each other and the Earth, while being humbly aware that there have been decades—life times—of wave action.

A footprint can be an impression left by the sole of a foot or shoe in a substrate’s pliable surface. The term ‘footprint’ can also refer to the area affected or occupied by something—typically a human activity or societal expression.

Climate change is an ecological footprint of our unintegrated history.

As a species, traumas of separation from the places that created us have led us to deny our animalness, our earthly belonging. We’ve lost trust in our senses and thus committed senseless acts in an effort to construct security.

Racism is a cultural footprint of our unintegrated history.

Separation from an animated life has led to the objectification of our surroundings and ourselves. We are all fugitive and colonist—departing from and arriving at seaports across the whole of the world—real and imagined.

These, and other crises facing modern society, are symptoms of long-term pathological dissociation: separation, exclusion, denial, denigration, objectification, and destruction. They are the geographic and biographic accounts of the traumatic history experienced by our ancestors, other species, and our planetary home. Storms have a tendency to resurface— en masse—the shells no one wanted.

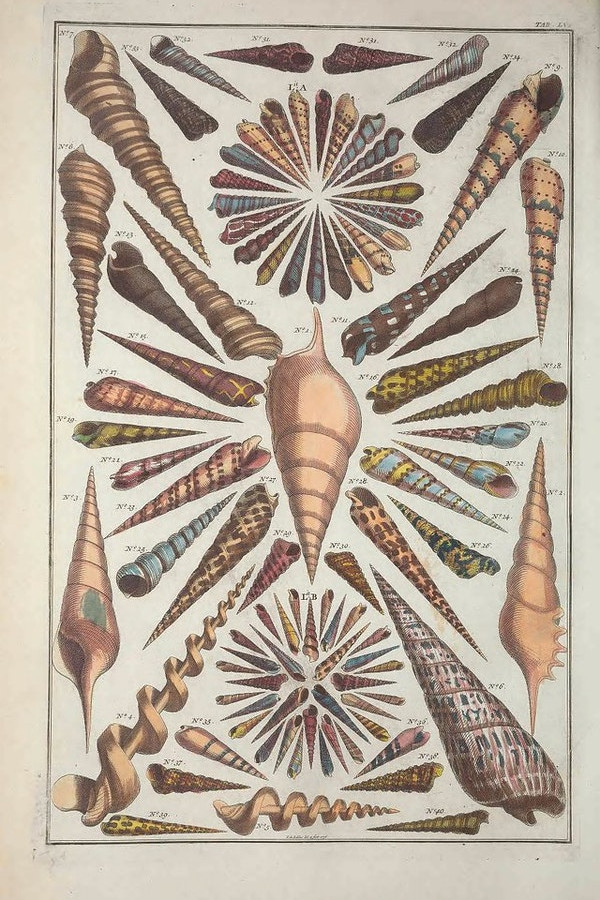

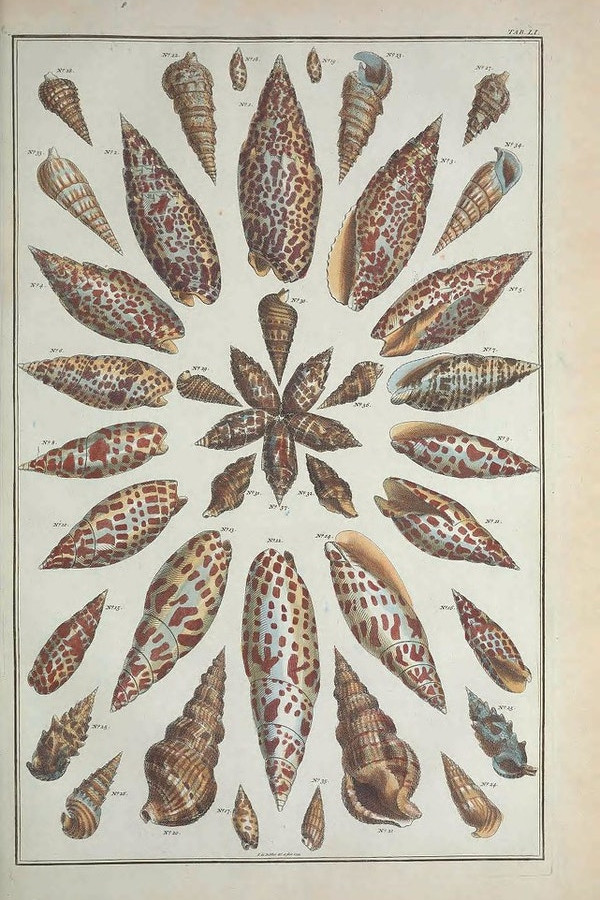

Thankfully, Nature informs the potential of human nature. Marine snails of the genus Xenophora are also collectors. They scavenge small rocks, shells, and debris from the ocean floor, adhering the fragments to their own shells—the way they show up in the world—as they grow, interval by interval. The outcome may initially come across as a bit messy, woefully disorganized, but beauty eventually arises out of the reanimation of discards. We are all collections of the treasures we gather from murky realms—those things brought to us by strong currents and upwellings with greater force than gravity’s hold in a crevasse.

Thomas Hübl continues, “…we find out that the absent parts of our social and individual life, are basically parts that you don’t see and that you don’t feel. I think that it is very powerful that in order to come back to sensing and seeing you will have to attend to what has been excluded.” This is individual and collective soul retrieval—to discover scattered parts of ourselves, reclaim them beautifully, and give them an embodied home, one that enables us to become ever more sense-able in the way we envision and live into the future, one that enables us to attend to the yet-to-arrive-traumas with greater resiliency.

Thomas Hübl continues, “…we find out that the absent parts of our social and individual life, are basically parts that you don’t see and that you don’t feel. I think that it is very powerful that in order to come back to sensing and seeing you will have to attend to what has been excluded.” This is individual and collective soul retrieval—to discover scattered parts of ourselves, reclaim them beautifully, and give them an embodied home, one that enables us to become ever more sense-able in the way we envision and live into the future, one that enables us to attend to the yet-to-arrive-traumas with greater resiliency.

So, then, in order to see the horizon, where we are headed individually and collectively, we must—from time to time—turn a soft gaze upon the excluded past, as well as the story-augmented and -distorted past. The visionary spirit needs to be able to listen carefully to the voice of integrated adulthood, rather than go skipping down the beach with adolescent abandon, proclaiming to the gulls above that it’ll never grow up.

Litchfield Beach gets its name from Litchfield Plantation, circa 1750. The old oaks, draped in Spanish moss, have watched rice transition from a slave-labored crop to a luxurious-wedding throw away.

How long before extreme weather events and sea-level rise engulf Litchfield, and all of the human and other-than-human tracks left upon that land?

For me, getting a true sense of ourselves necessitates that we meet the shores our beliefs with inquiry. We call up questions to lap—sometimes gently, sometimes with vigorous intent—at forms that have bounded the solid ground on which we and our ancestors have stood. I’ve come to regard answers as transient guideposts: buoys anchored in shifting sands. Even the stars betray our confidence at some point; we can’t navigate by the same storied-constellations forever. Questions, though, they are timeless.

Looking back, what do the changing tides bring into your awareness?

Xenophora. Xeno, from the Greek ‘xenos’ meaning a stranger. Phora, also Greek, meaning to bear, as in to bear children. I think this is what life’s greatest questions ask of us: to bear the strangers of the past as if they are our children.

Looking back, what does the child of you want to collect and place in your favorite sand bucket?