Holacracy | An Emergent Order System

Kosmos | How are systems of dynamic governance transforming our organizations?

Brian Robertson | Sociocracy, or dynamic governance, still uses a top-down management hierarchy as its fundamental power structure. It gives you a policy-setting vehicle that encompasses every team, but that policy-setting vehicle is using basically a modified quorum of consensus. With Holacracy there is no top-down management hierarchy. It’s an entirely different power structure. Holacracy also doesn’t use anything that looks like consensus, at least not when it’s done correctly.

What makes Holacracy unique is that it gives people a taste of real genuine power without trumping others’ power, of sharing power together, in a framework where no one else is responsible for taking care of your issues. You are responsible for solving your tensions, as we say. In management hierarchies, the boss is responsible for solving a lot of your issues.

Kosmos | So in a sense, this is a personal practice as well as a system.

BR | It’s kind of a stealth spiritual practice. … It’s a personal development or a transformative practice.

Our organizations are facing environments where the complexity is far greater than anything they’ve faced before. What I often say in my trainings is: Imagine you were an executive 100 years ago, and the level of complexity you would have faced in the company, the demands that would have come in from the outside world. How many messages would you have needed to process in a day? 100 years ago, very few. 10, 20. But today, with all the channels that send us inbound messages, it’s at least 10 times if not 100 times that. Management hierarchy worked beautifully in the complexity we faced back then.

People will sometimes think that I’m anti-management hierarchy. I’m not. I think it’s a beautiful way to run an organization – when complexity is lower. I think it just fails to keep up with most of our environments today. We’re not sitting here talking about alternatives to management hierarchy because management hierarchy failed us for centuries. We’re here because management hierarchy succeeded wildly. In fact, it helped create a world more complex than it could manage. Today, the environment is just demanding more.

I use the human body as a great metaphor. It’s a wonderful way of dealing with complexity. In the human body, there is no “CEO cell” telling the other cells what to do. There’s also no management hierarchy of cells with command authority over other cells. What we have instead is a more holarchic structure. Every cell is both autonomous and also operates as part of a larger function, a larger organ. This larger organ doesn’t violate the autonomy of the cell by telling it how to organize. Each of these cells, and organs, in the body has autonomy and they’re all connected to the others. That’s nature’s way of dealing with complex systems. I think our companies are going to need look a lot more like that to deal with the level of complexity in the world today.

Kosmos | You touched on a couple of points that are really interesting to me. The idea of emergent order reminds me of other natural systems like ecosystems, rainforests. No one needs to tell a rainforest how to be a rainforest, or a coral reef how to self-organize. Is that what you mean?

BR | Yes, that’s true, although Holacracy wasn’t designed with an intention to parallel the natural world or anything else. Holacracy was created much more empirically or evolutionarily, through experimentation. It itself is an emergent order system.

Holacracy is not the result of intelligent design. I didn’t go out and say, “Great, here’s the way nature works. How do I get a company to work like that?” Holacracy came from years of experimentation, seeing what works, and changing what doesn’t. This is exactly what Holacracy brings to companies – the ability to constantly experiment and adapt. It converts organizations into evolutionary systems.

But then when I step back and look at what emerged from that experimentation and seek out the mental models best illustrate what it is and how it works, they are all mental models drawn from the natural world. I found this much more validating than if I had designed the system using those as a theoretical framework.

Kosmos | I was really curious about a transformational moment you described in your TED Talk – the story of the voltage meter.

BR | This happened in the very beginning of my journey, and it became a very powerful metaphor for me. I guess nearly dying can have that effect.

At the time I was studying to get my private pilot’s license. I only had 20-something hours of flight experience under my belt. It was my first solo flight away from my home airport, so I was hundreds of miles away from anyone with no instructor for the first time. I was only 50 or 100 miles into the flight when my low voltage light came on. I didn’t know what that meant because they don’t teach you much about the hardware of the plane at that point in your learning. I guessed it had something to do with the electrical system, but since I didn’t know much about the airplane, so my instinct was to check the other instruments. I scanned every other instrument on that control panel. My air speed was fine. I wasn’t losing speed. My altitude was fine and my navigation was perfectly on course. Every other instrument said that everything was fine.

So my instinct was, “This must not be that big of a problem. Only one instrument is sensing anything wrong, so I’m going to ignore it and just keep flying. I’ll check it out later when I land. It must not be that important.” As it turns out, that was a really bad decision. That low voltage light was tuned into information that no other instrument had, and I nearly crashed the plane that day. I ended up completely lost in a storm with no radios, no lights, no navigation, almost out of fuel, and violating air space in a major international airport. It was a bad scenario. I did make it out of it, but barely.

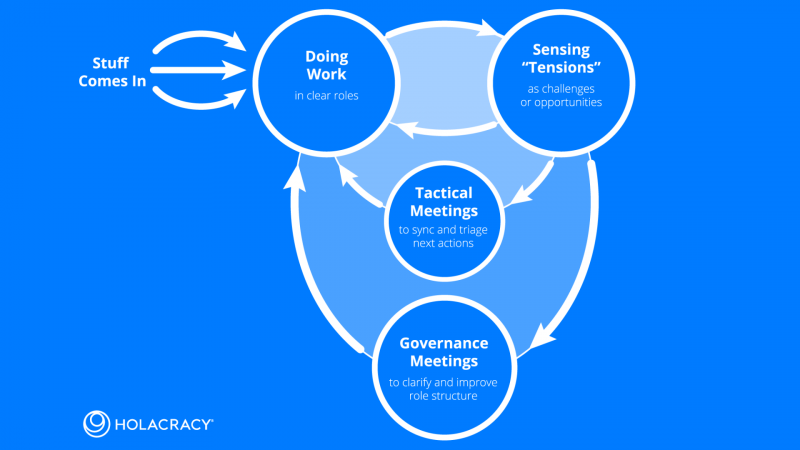

When I reflected on this, I realized this is what happens in organizations all the time. One person, or maybe a small group, sees something that no one else can see. And then they have a really hard time driving change because everyone else just kind of outvotes them. I often talk about the tyranny of consensus, which is where everyone has a voice but nobody can drive change because you can’t change anything unless everyone sees it all the same way. This is difficult for that one lone voice who wants to change something. The question for me was, how do I build a system where anything sensed by anyone anywhere in the company has somewhere to go where it can rapidly and reliably drive meaningful change?

Kosmos | Did your life change after that experience?

BR | Yeah, it was weird. It was almost like my life was already changing and ready to change in exactly that way, and that experience kind of gave me the metaphor I needed to put the pieces together. I’d almost say I was perfectly ready for that experience, rather than that experience alone changing something for me. It’s funny how that works.

My old way of making sense of the world, my old way of thinking about good leadership, everything was just crumbling. I was in this state of not knowing and embracing the unknown, and saying, “All right, I’m not going to pretend I have all the answers now. In fact, I’m going to realize just how much I don’t know,”

Kosmos | Our greatest transformations often occur during our darkest moments.

BR | It was one of three in my professional journey with this, and each one, interestingly, has catapulted the development of my work massively afterwards.

Kosmos | The hero’s journey. It’s helpful for people to hear that story, because we often feel despair, and I think especially younger people. What role can Holacracy play in transforming some of our despair about our work life or the meaning of work itself?

BR | I think there’s a hunger for more meaning, especially among a younger generation. When was the last time you heard a millennial saying, “I just want a job that provides me a steady paycheck to put food on the table”? For my grandparents’ generation, that was enough. Now there’s a hunger for meaning and purpose and autonomy. I see this struggle even in very purpose-driven organizations. It’s one thing to have an organization that serves a compelling purpose. That helps. But when that purpose-driven organization is run in a very conventional way, people inside often feel very disconnected from that purpose. In a conventional system, it can be hard for individuals to have enough autonomy to drive change, to have a meaningful impact.

With Holacracy, it’s not just the organization that has a purpose; every role inside the organization has a clear purpose that’s connected to the organization’s purpose, and each individual has real deep autonomy to lead their part of it. And you no longer find yourself these parent-child dynamics because roles have real authority, and there is no CEO or manager. In my company, it’s a regular occurrence where I’ll go to one of my colleagues and give them a convincing argument of, “Here’s what I think you should do,” and they’ll turn to me and say, “Thanks for your argument; I’m going to go a different direction.” Or if I get too aggressive they’ll even remind me and say, “You don’t have the authority to tell me what to do.” That is such a shift.

Kosmos | I think that there’s a misconception about Holacracy that it’s leaderless. What is the difference between leadership and authority? And also what have you discovered in yourself about conscious leadership?

BR | I find it beautiful and ironic that most of the things that people think of as “getting in the way” of progress are exactly the things Holacracy embraces, but reframed. For example, we often think of structure as all the policies and the bureaucracy of companies. We think that structure gets in the way. But if you want to have a deeply empowering environment you can’t just throw structure out. If you go to your team tomorrow and you say, “Guess what guys, you’re all empowered, no structure,” you won’t get an empowered team. What you get is a bunch of confused people. People know there’s a need to have some limits on what they really shouldn’t do. And if you don’t know what you can’t do, then you also don’t know what you can do. If you don’t know the limits of your power, then you don’t know your power.

Kosmos | So Holacracy, ironically, is more structured, not less, than conventional hierarchies?

We each have authority to lead our role. It’s not a leaderless environment; it’s a leader-full environment. We each have this autonomous leadership in an environment that sets clear expectations and clear bounds. I know what’s not mine to control, or not mine to decide, because it falls in my colleague’s area. And also I know what to expect of my colleagues and what they can expect from me. Any one of my colleagues can come to me and say, “Hey, you’re accountable for this. Tell me how you’re meeting that accountability.” So it’s clear autonomy, clear authority, but within clear limits and clear responsibility.

So this is one of the things I love about Holacracy. Instead of rejecting autocratic decision-making, or rejecting structure, or rejecting clarity, it embraces these, but it embraces them along with the freedom and flexibility that we see as their opposite.

Kosmos | Very Dao.

BR | The seeds of each are in its opposite, absolutely…if you reject something that appears to be an opposite of what you want, then you’re actually hurting the very thing that you value.

The capacity that does seem to matter is more a maturity, what I call a vertical capacity. For example, openness, if you’re open to the fact that there might be other ways of seeing things, other perspectives, other points of view. The more open somebody is, the more they’re going to thrive in this system. It actually doesn’t matter what their point of view is, or what they personally value. What matters more is the way they hold these values or perspectives. Do they reject and judge and dismiss anyone that has a different set of values than they do? Or do they get curious? Do they get open? Do they explore the difference?

Or can they actually integrate the differences between their perspectives and the perspectives of others? This requires even greater maturity, the ability to see these differences and create space for both together. That is not to say Holacracy doesn’t work when people are earlier in that journey; it does. What I find, though, is that there’s a fairly high bar for the leader who’s actually making the decision to adopt Holacracy. The leaders that are adopting this today are remarkable people with a lot of developmental capacity. They have their own way of being in the world is rather rich, nuanced, mature.

I often get asked the question, “How do we get people ready for doing this?” Adopting Holacracy is a huge change, and I think when people ask me that they’re rightly intuiting that this will require new capacities for most people. But the answer is you don’t get them ready before you do it. We get them ready through their practice. It’s kind of like asking somebody, “How do you get ready to be a master meditator?” Well, you just go meditate. You don’t try to prepare for it. That would be missing the entire point.

My path to Holacracy was not very saint-like. I needed something that was going to protect the organization from my own tendency to want to control everything. But now when I go to a colleague and I start pushing and say, “No, here’s how it should be,” they just hold up a mirror and say, “Wait a minute. Do you have the authority to make this decision?” And I look at the roles and I say, “Sure enough, I don’t,” so I pitch them on making the decision.

If I try to talk over somebody in our governance meeting and dominate the space, there is a really strong facilitated process, and the facilitator just stops me, immediately interrupts me to say, “Wait a minute.” Holacracy is based in a set of rules; there’s a Constitution that defines the power structure.

The facilitator has the authority to just cut somebody off if they try to dominate the space and talk over everybody. That same process, also defined by the Constitution, makes sure everyone does have space to share their questions, reactions, and concerns. So for the more introverted folks, they can just wait for their turn. They don’t have to fight for space because they know that they will get a turn in this process.

Kosmos | It sounds like in the constitution itself you have some of these other built-in practices of empathy, compassion, and also non-violent communication, (NVC), deep listening. Are these parts of the actual practice?

BR | When I look at what an organization practicing Holacracy maturely does, you get things that look like NVC happening naturally even from people never trained in that practice. And I find that fascinating.

Kosmos | That is fascinating.

BR | Yeah, the system builds those capacities. Does it force them reliably? No. You could still have somebody dumping judgments all over somebody in this system. That’s still possible. But it’s more likely that that behavior will be transformed over time and that people will naturally develop the capacities to communicate differently.

If you add something like NVC into a company doing Holacracy, it’s going to help; it’s going to accelerate the journey. So I often recommend that companies running with Holacracy go work on developing a conscious communication practice. Because it will help. It will accelerate your team’s development. But one of the beauties of Holacracy is that if you really do this well consistently for a while, those capacities get naturally developed or enhanced.

Kosmos | How do you see this evolving from this point on? In other words, do you think Holacracy has a role in governance?

BR | Yeah, interesting you mention governance. There are actually many government agencies now practicing Holacracy, and I’m really curious to see where that will go. There are multiple government agencies now in Dubai that are doing it. There’s one in the U.S. There’s a whole city in Canada, a whole town, that is trying to organize the entire town using Holacracy. Part of the city of Amsterdam is doing Holacracy in one department. There are many interesting cases of experimentation in that area.

Instead of asking how do we get better top-down control, I think a more interesting question is how can we change the fundamental frame to not need top-down control? The question of how do we get better legislatures is, I think, missing the point. How do we create a system where we don’t need the same kind of top-down control? We have an emergent system that has the potential to adapt and take care of our needs for governance, where governance could be distributed throughout the system. Governance could be kind of just like breathing; meaning that it just happens; it’s not something that is handed and controlled top-down.

To achieve that, I think we would need a whole lot of purpose-driven organizations, and we need to start seeing them interlinked together. Holacracy has structures that are equipped to do that. We’re seeing examples now of companies interlinking to govern their commons. I think that can get really interesting. You have purpose-driven entities that are starting to interlink to govern shared context across the company boundaries and with multiple stakeholders having a voice in that governance, not just one.

Holacracy, you could say, is management without managers. It’s decentralized management that uses a very different process to get some of the same results. You still have order. You still have structure. You still have clarity. You still have rules. You still have all those things. You just achieve them completely differently. Could we do the same in our societies? I think so.

Kosmos | Beautiful. Thank you so much.