Rights shared by all citizens typically inspire broad agreement amongst community members, while responsibilities differ wildly based on possibility, opportunity, status, wealth, and several other factors. The opportunities structure within countries is often very unequally distributed. We cannot deny socio-economic differences and multiple forms of discrimination within and across nations. On a global level, we see even greater differences in economic development, political systems, and individual freedom. The nation-states remain the strongest denominator of identity. If we look at surveys such as the World Values Survey, people around the world first identify as a citizen of a country instead of thinking of themselves as a citizen of the world. However, global citizenship as an overarching and fluid concept is not in contrast to the narrower ideas of national citizenship. It is not related to passports or a critique of patriotism. Instead, it suggests another layer of citizenship that transcends nationalism and points toward the shared destiny we face as humans in this world.

The challenge to conceptually differentiate global citizenship from national citizenships is that global citizenship now seems beyond the reach of large sections of society because the concept appears mentally incompatible with our national identity. If your national identity is at odds with your ideas of citizenship and its associated rights, then global citizenship will remain a mirage. Global citizenship, though, is not aiming to compete with national, regional, or ethnic identities. Within global citizenship, there is even ample room for patriotism, however, not as one nation before others, but as a sense of responsibility towards the world departing from one’s own feeling of belonging. Global citizenship acknowledges origins and belongings but argues for an overarching idea of shared responsibility towards each other, transcending national borders.

However, global citizenship does conflict with strong nationalism. The growing nationalism of stagnating industrial economies was built on the back of pro-globalization and pro- immigration policies. These upsides have already been socially and economically absorbed over two or three generations. Still, the current task of equitable sharing of resources and opportunities has become a polarizing social and political choice in all advanced nations. This is because it would require these societies to recalibrate, and there is a fear of losing their worth and sacrificing their quality of life by being accommodative for the sake of others. The strong nation-first rhetoric we hear is in contrast with multilateralism and global collaboration. Understandably, governments need to fulfill their citizens’ needs first, but when nationalism leads to isolationism and hostility, it conflicts with global partnerships for addressing shared problems.

To counter such sentiments, it seems advisable to value and promote traits such as empathy, respect for diversity and collaboration across boundaries. However, these aspects of global citizenship are not yet institutionalized as universal values across the world. It is not part of the lexicon of politicians, parents, teachers, and caregivers. There is a whole generation of young people who are not taught what it means to accept diversity of thought. Remedial influences for such an audience remain unproven because they display monolithic thinking, which is extremely difficult to change without strong stimuli. For global citizenship to become a universal concept, we would need to agree with such fundamental values to be taught to younger generations to internalize the spirit of open debate and accept differing world views.

Often those who travel extensively or have access to multiple cultures are considered to be global citizens. This is because it is somehow implied that people who have visited different regions of the world are more open-minded than others. However, this cosmopolitan view lacks nuance and depth. It is an elitist concept which does not withstand a closer test. If global citizenship is interpreted only as a cosmopolitan attitude, it will rule out most of the world’s population. It implies that those belonging to lower socio-economic backgrounds who lack travel opportunities can never become global citizens. Experiences in other cultures may help form one’s own identity in relation to others. Still, traits mentioned such as empathy, care for the world and valuing diversity are not dependent on socio-economic status. If global citizenship is to be a universal overarching concept, then it cannot be tied to monetary resources but needs to be based on the common ground of all people being citizens of one planet that we need to protect and care for, foremost through local tangible actions that positively influence global developments.

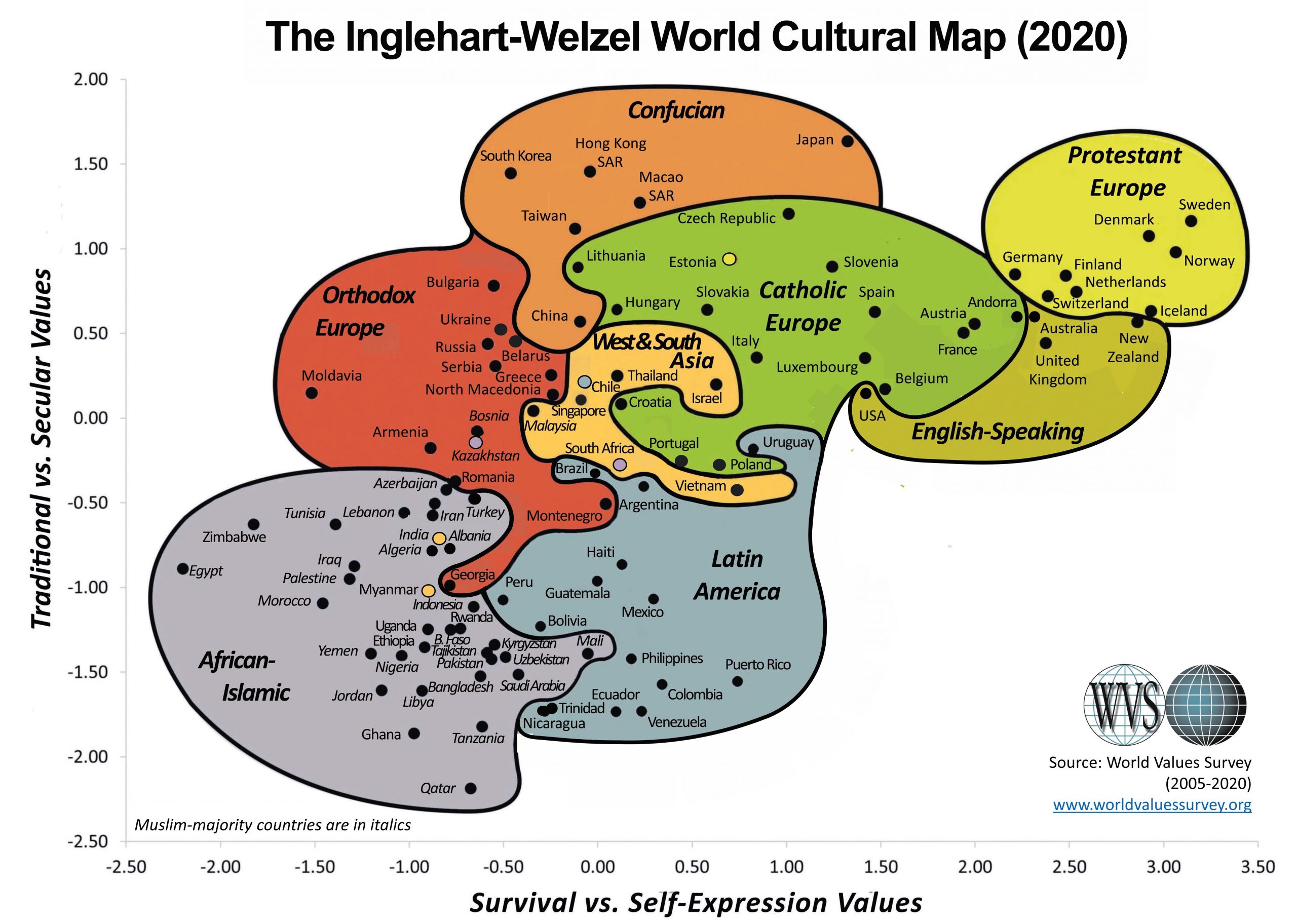

Besides, global citizenship must acknowledge the diversity of people regarding their upbringing, their cultural, ethnic, religious, regional, and national influences when forming their identities. A starting point to understand cross-cultural variations of values across the globe is the World Values Survey (WVS). This global research project aims to identify and group people in different countries on several cultural parameters and analyze societies based on the data. It specifically asks for opinions and influence of markers such as the impact of globalization, the role of religion, culture, family, and the attitudes toward ethnic minorities, foreigners, and environmental conservation. The survey results can add to the framework of global citizenship by showcasing on a more macro level the major differences in prominent attitudes throughout the world. The data is presented on a national level, though, and therefore can only serve as the first point of orientation as national societies themselves can be highly heterogeneous.

One interesting outcome of the survey is the Inglehart-Welzel Cultural Map (see graph no. 1). It plots societies based on their position relative to secular-rational vs. traditional values on the vertical axis, and survival instincts vs. self-expressionist instincts on the horizontal axis. Traditional values here associate with a nationalistic outlook in which traditional institutions are sought to be preserved. Secular-rational values associate with an opposite trend, accepting new institutions into its fold and destigmatizing taboo topics. The survivalist societies tend to exhibit lower thresholds of trust and tolerance and yearn for economic security. Towards the right of the spectrum lie the societies emphasizing self-expression, marked by greater democratization and tolerance.

Graph 1: The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map 2020. Source: The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map – World Values Survey 7 (2020) [Provisional version].

It is an insightful exercise to place yourself on the Inglehart-Welzel map because your ascribed values-based identity may significantly diverge from your national identity. Culture is essentially institutionalized knowledge living inside of people. We gain fluency and nuance in this knowledge by interacting with everyone around us. True global citizenship should allow us to hold multiple cultures and realities within us with some confidence in our ability to switch and navigate between them instead of assigning to one-dimensional identities.

With the world map divided into cartographic regions of modern nation-states, the puzzle to be solved by the advocates of global citizenship is the accommodation of diversity under an overarching framework of inclusion within a broader society, characterized by a feeling of belonging to the global community. Placing oneself on the world map gives one a sense of control and enables one to assess situations from a bird’s eye view of prevailing conditions. Hence, a person’s global identity in the world, while uncontested, forms an integral part of global citizenship and allows one to view things from varying distances in a changing milieu.

In conclusion, global citizenship is not the opposite of national citizenship. Quite the contrary: as a universal concept, it embraces the diversity in nation-influenced convictions as much as religious, secular, traditional or modern values. Its universality lies in mutual respect and the willingness and ability to collaborate across boundaries to solve the global problems we humans face. It has a firm grounding in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and a framework of action in the SDGs. However, the concept goes beyond that. Its universality lies in a familiar feeling and ethic of care for the world and each other. It is not uniform in terms of culture, religions, thoughts, and actions but on a responsible way of life where we take care of others and the environment within our spheres of influence.

Citation: The Melton Foundation (2021). The State of Global Citizenship Whitepaper about an emerging concept. Willington: MF.

Licensed under Creative Commons

![]()

The moral rationalism of Purism tells us exactly where homogeneity and pluralism should each sit in the context of global, universal citizens. In short, the things we desire can be pluralistic; the things we need need to be consistent, ordered, and homogenous.

https://www.academia.edu/60656070/Purism_Logic_as_the_basis_of_morality