Flesh and Blood | On the Sacraments of Survival

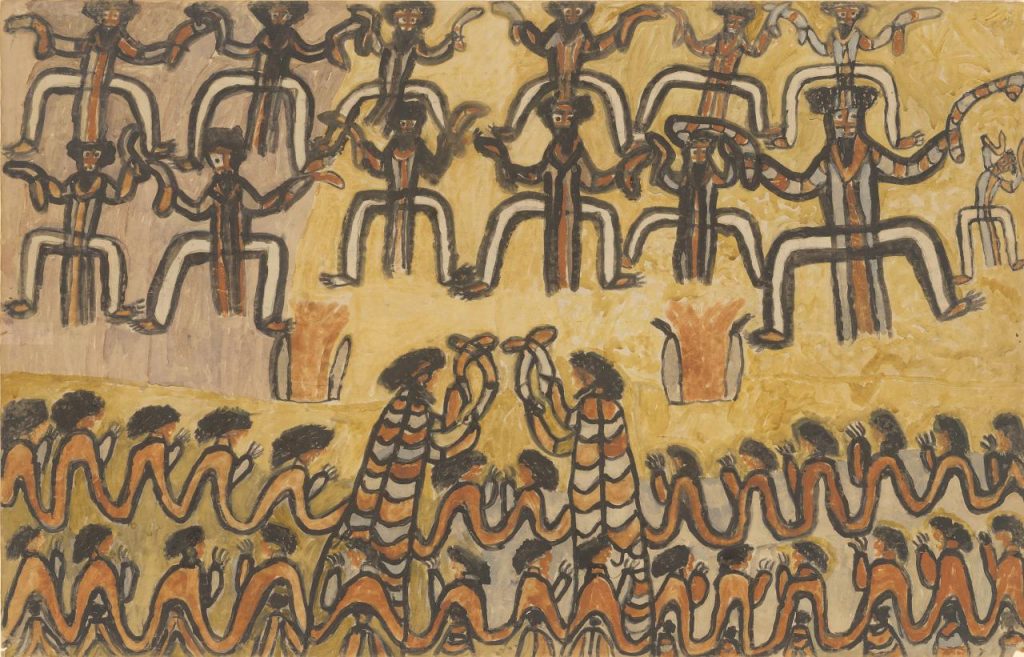

featured image | by Elisabeth Jurenka

It is good knowing that glasses

are to drink from;

the bad thing is not to know

what thirst is for.1

– Antonio Machado,

Translated by Robert Bly

A lifetime ago, at the invitation of an elder and friend, alongside some twenty others, I made a vow. It contained a commitment to go out into the wilderness for four days and nights at a time, once a year for four years and sit. Once in a frozen forest, once in a summer swarm, once at the edge of the ocean, and once in a charred ravine. Feeding the four directions of our telluric turning. In the name of those who would come after us, we pledged to sink into the ground and surrender to being smoked by time.

The instructions were succinct: we were to sit down and stay still, fixed and grounded. To fast. It seems strange terminology, given the slowness imposed and required. “To fast” means “to abstain from food,” but deeper down we find its roots, which mean “to hold, to guard firmly” from the proto-Germanic fastanan.2 Eventually, the word came to mean “to hold oneself to observance,” which is what we were tasked with – to fasten ourselves to the firmament of place, without rest, reassurance, movement or ministration; without food or water.

Previously a stranger to such traditions, I eventually came to digest the words of the late Dagara ritualist Malidoma Somé, who wrote “the emptier your stomach is, the easier it will be for you to learn. Other things within us are better nurtured when the body is not fed.”3 A little more kindred following the four prostrations, I lay these considerations down as a small piece of what I might have learned out there, so that together we might feast on an empty stomach.

These endeavors amounted to a kind of initiation. But, if you asked us, years later, to deliberate and decide what we were initiated into, you’d have a hung jury. Whether or not we were initiated into anything remains a mystery, but it is that mystery and a willingness to feed it, to ensure that it continues to have a place at the edges of our days, that requires me to leave so much of what happened out there out there. Perhaps, you might understand that much of what is sacred is also secret, that for the holy to be heard, a silent surrender might be a prerequisite. While everything in this world belongs, not all of it belongs to everyone or all at once. This is a kind of mercy that honours the original understanding of hierarchy as “a sacred order.”

Such matters, such katabatic undertakings, can prod people into deeper relationships with the underworld, with their mortality, their kin and their nourishment. They can remind us how food and water are the sustaining sentient bodies of all animate beings. While this might not be a recurring reality when you sit down to eat a meal, we can still apprentice such relationships, in part, by knowing what it costs us to abstain from them. In our time, this inquiry also wonders what happens when we refuse to fast, when our will to survive forbids and forsakes the abstention.

Hunger and Thirst

We can say with a degree of fidelity that close to all of our human ancestors’ days were defined by their relationships to sustenance, by working with those who nourish, by working for them and being worked by them. The elements, animals, plants, soils, and spirits. Humans have often deified their relationships with each, to both divine and disastrous degrees. In our age, food and water are either the foundation for life’s prolongation or the primary factor in its subversion. They can nourish or they can neutralize.

Today, though, it is often only the presence of sustenance that gets acknowledged. The absence of such things is almost exclusively spoken of as poverty. But what if this contemporary poverty arises not from sustenance’s presence, but from having forgotten what is absent in that recognition?

During the time-out-of-time that accompanied such intense fasting, my father’s voice echoed around me, recalling his peasant childhood some seventy years previous. “I remember hunger,” he once confessed. An affliction that I, myself, never encountered up until the end of my youth. And while the way he spoke in such moments might have ciphered the memory of an Old Country insecurity, those endless hours of fasting and invocation invited not a feeling, but a form, a figure. A Hunger. The chalk outline of my desire, subsumed by the prayer-tie perimeter surrounding those days, etched a familiar forgetting, as well as its unlikely re-cognition.

What we refer to as scarcity today was forever a factor in the lives of our dead. A lack of food and water. For them and for the countless peasants whose dirt-drenched fingerprints continue to forge kinship between people and place, it is often the scarcity of sustenance that determines life’s trajectory. Not simply a fear that “there won’t be enough,” but a lived understanding and relationship to limit, one that can proffer prayers on the lips, preceding each sip, each taste, each morsel as a communion. Gratitude, in other words.

I’m reminded of the stereotypes of elder generations of Europeans and Africans who apparently rarely bathed throughout their lives and imagine that their silty skin and scents didn’t emerge from a shortage of water. Instead, their lack of cleanliness arose from a godliness that most of us, today, have forgotten. That is, to ensure they could continue to draw from the deep well of religious reverence that fed what sustained them, they largely withdrew from the ability to soak, submerge or siphon. Not because the elixir of life was in short supply, but because they held it in such high and holy regard.

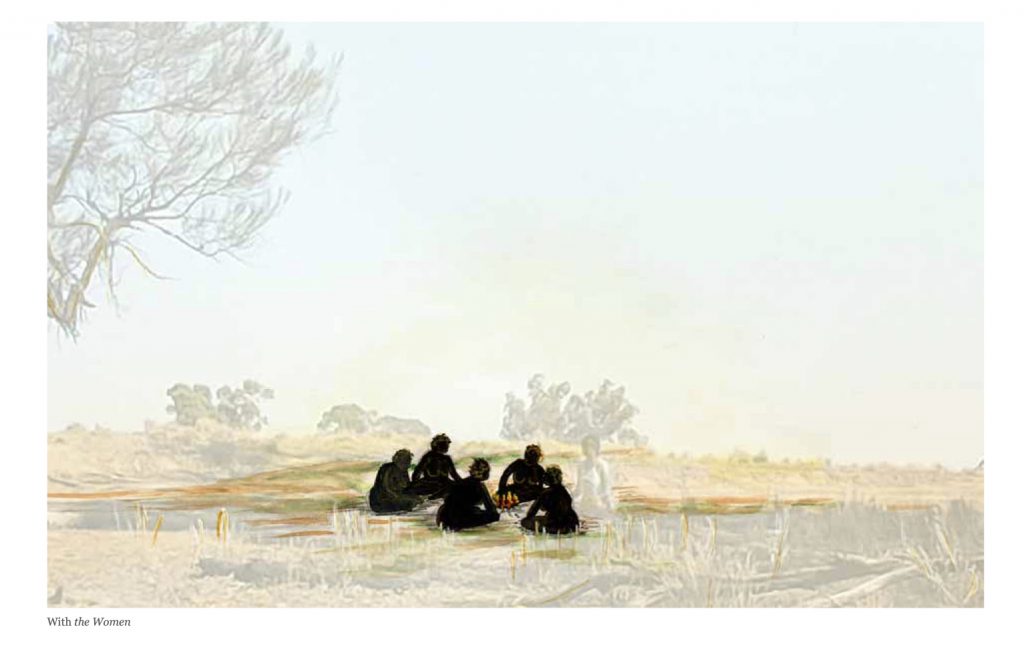

In myriad cultures, past and present, local and lineal foods (both as plants and animals) are revered as deities, just as their wellsprings, rivers, and mountains often are. I wonder about our ancestors, the ones young enough to be considered “ours,” constantly sensing those consecrated presences nearby. At times, I dream about our Old Ones, perhaps seeding, husbanding, and harvesting their food or water, and whether they approached the former, just as they might have the latter, as aware, divine and even kindred – as Flesh and Blood.

Contending with all that I had encountered out there on those long, dark nights of the soul, I felt Hunger and Thirst enter into me, not as the mere absence of food and water, but as presences, as specters. I asked myself then, as I ask you now, what if Hunger and Thirst are names of the numinous? What if they are Gods whom we’ve ghosted? What if our inability to recognize these apparent afflictions, these telluric needs as deities and the sustaining sentiences of our days subverts our relationships to food and water, to Flesh and Blood? And what if any achieved and enduring kinship with our nourishment demands such fastidious remembrance, such material and memorial offerings? What is the cost of gluttony, of surplus, of unquestioned excess, if not a mortgage (i.e. “death pledge”) that starves the world in order to feed only the human?

A Recipe

If you’re lucky, as I sometimes was, after the second full day, your ideas about dying slowly and defiantly give way to your dying. A softness descends, while a subtle strength persists. Appetite is all but an afterthought now. Hunger and Thirst satiate. It’s a strange dynamic. And as the days turn to hours into minutes, your mind exhausts itself. If you’re lucky.

You ask for forgiveness for cursing the scorching sun, the swarming mosquitoes, the icy ground and yourself for signing up. You pray that your life continues until all that’s left to do is to pray that life continues, with or without you. You feel tears thick as cream inching up out of your eyes, wondering how close you are to the last drops. Somehow, you sense that those liquid oblations are worth more to the world than what remains of your raisin frame. So you wait and you pray and for a very long time, this is the afterlife.

And then, the end. Like a candle flame flickering through the veil between worlds, a voice, one that’s been whispering your name over prayer beads and bells all this time, quietly announces itself. With utmost tenderness, you are lifted and led back, cleaved open, to a circle of your still-dying companions.

Alongside them, you can barely hold the freshly-carved spoon to the trembling and anointed threshold of your mouth. Despite your pain and prostration, and even despite your resolve, you will forget this moment. That wooden offering, sliced and shorn under lunar swell and supplication, bearing bone broth myrrh and mercy, about to baptize your body, comes with an uncanny caveat. As much as you will want to forget and as much as you certainly will, do what you can to remember this moment.

Without a lived memory of Hunger and Thirst in our days, without a lived relationship to the care and courtship required to conjure Flesh and Blood, neither are properly satiated.

When nourishment is known only by our need to feed, we squander an understanding of what goes unfed and the banquet table of our times shrinks, losing another guest, another host, foreclosing on another house of hospitality.

To hold oneself to observance is to peer into the unseen, the unrequited, and the dismembered. This was the offering and the ask at the end of each fast – to gather in, to re-member. To break-fast on the final morning, with the estranged, simmering scent of animal stock in the air, a plea was offered up as a prayer, a feast rendered with the fat of memory. A grace offered up as the food:

Whatever you do, try not to forget…

[that Hunger and Thirst are the children of Death,

just as Flesh and Blood are the children of Life].

Let that linger. Let that disclaimed lineage in. It is yours, after all.

Perhaps, now, you can sense it. Maybe you can begin to feel it, to remember that the former are not the absence of the latter, but their twins, the rest of the story, and maybe even the roots of it.

We can be grateful that there are still people alive today who remember such things. We can be humbled by their willingness to act on the understanding of what can come to pass when those things are forgotten. These elders have learned that a deliberate and onerous reunion with Death and his kin is mandatory to temper what each of them can become when they are neglected and malnourished.

Modern Masks

In our age, Hunger and Thirst are routinely subsumed into systems of scarcity, disguised and seldom recognizable as such. These Gods fall famished and like anyone, go looking for ways to feed, which in their cases, are ways to starve.

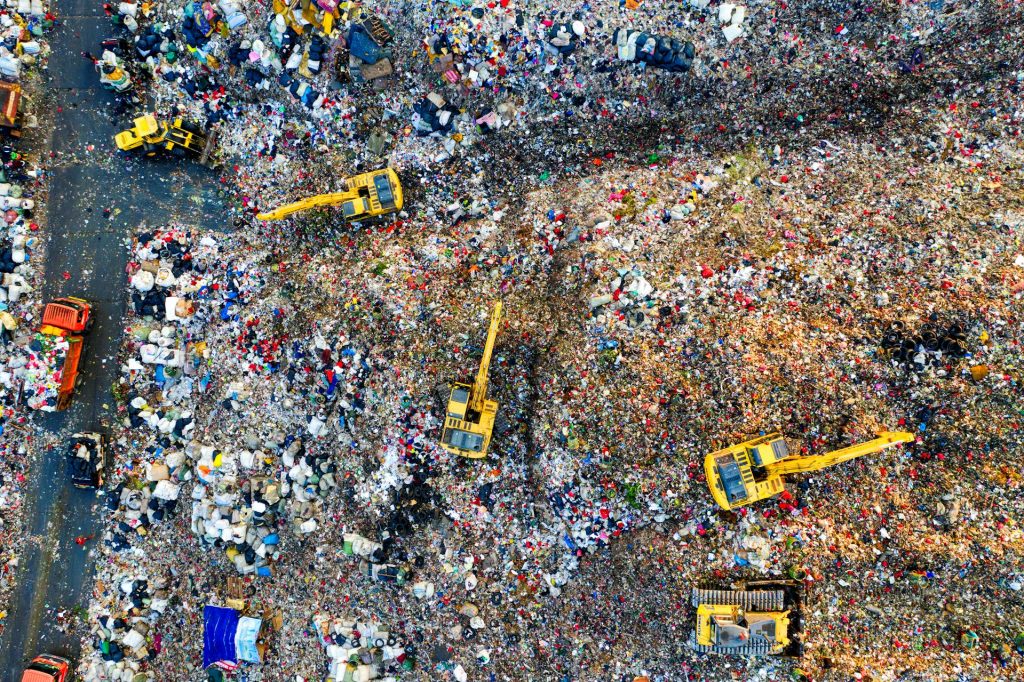

We can ask if GMO and Terminator seeds and the rivers we turn into sewers aren’t a consequence of this rupture. Not a quick fix to our dilemmas, but their deepening. We can wonder about the modern micromyths of development that sell guilt and scarcity, in part, through images of bloated and starving children, elsewhere. Not the ritual feeding of Hunger and Thirst, but instead, the fetishization of their disappearance from our lives. All of this, as a way of concealing what’s been done to Flesh and Blood, typically in our names.

The solutions that modern institutions solicit too often spring from the poverty that prefaced the problems in question. And so I ask you whether or not we unknowingly unleash Hunger and Thirst onto the world as a result of what we’ve taken from Flesh and Blood, both at present and ancestrally. The phantasmagoric fallout, in other words. And what have we taken from them, you might ask? Their twins, of course, but more emphatically, their kinship, their wholeness and their diets – this last word which signifies both our daily bread and our abstention from it. The segregation of Flesh from Hunger and Blood from Thirst is mirrored in the global food system. The consequence is clear: many must fast, so that a few can fatten.

Could it be, then, that the supermarket invitation to rabid gluttony and the access to it has vilified a capacity to fast – to hold oneself to observance, to be a faithful witness to the times? Could it be that in the threads of ancestral memories, ones that stitch Hunger and Thirst throughout, we have decried what were previously and properly deities in the lives of our people? What if the globalized food systems, the plumbing, the irrigation, the slaughter factories, the supply chains, and the mechanization of each are all consequences of this – not the deification of Hunger and Thirst, but their demonization and exile (as a result of being entered into the oasis of manufactured abundance)? What if Hunger and Thirst were cast as monsters only upon our ability to outlive, to outgrow, and to outrun them, no matter how fleeting that flight may be? And what if our ability and willingness to fast, to go without, to limit ourselves, kept all of that at bay?

Scarcity and surplus seem to be complementary opposites, forces that serve each other in their equanimity. Gain too much of one and the other becomes necessary to reincarnate the true cost and value of each. Among privileged people, “modern” as it’s often said, who not only have access to food but the means to purchase it, how is it that our grace-making rituals have disappeared from our meals? How do the ways we eat and drink banish Hunger & Thirst?

How is it that the more food we produce and consume the less appreciative of it we become? At what point did “gratification” stop being a synonym for “gratitude?”

Within the contemporary calendar of modern peoples, praise typically begins in spring and ends with the sway of falling leaves. The touchdown of rain and snow is sometimes referred to as “inclement,” regardless of water’s millennial associations as the elixir of life. Only certain seasons are celebrated, disgracing or escaping others while ignoring their subsequent dilation, volatility and destruction. Like Flesh and Blood, like Hunger and Thirst, we could ask how our current climatic calamities are consequences of our forgetting to feed the sentient architectures of our broader ecologies.

The countless reasons that led us toward those fasts in the first place are still very much in the world today, more pronounced and perilous than they were when we began. These questions that I’ve courted and laid in front of you are, in part, an attempt to earn that privilege, retroactively. They are a testament wrapped up in a plea, a grace that tries to recall all of the meals that lacked one.

The First Ancestor

Among so many rooted peoples, past and present, the plants and animals of their sustenance are and were understood as forebears. As a friend of mine has proclaimed on occasion, “the thing that fed your first ancestor is your first ancestor.” Those who have nourished your life and your peoples’ lives are, in many places, known both as deities and ancestors. They are the royalty rooting your family tree, the progenitors of your very existence in the world. They are the inflection on the gratitude conjured from your tongue, if it is conjured. And so, what becomes of Life and Sustenance without a relationship to Death and Decay? How can we engage in the slow and sacred act of eating, of communion, of visceral regeneration if we’ve never learned to fast?

Down and into the lineage of language, we find the verb “to fast” as a synonym for the verb “to forbear,” which also means “to abstain, to do without, [and] to endure the absence of.”4 Paradoxically, “to forbear” also means “to which we have, or that which has been, borne forward.” To bear, to fast and to fasten ourselves to Hunger and Thirst, as much as we might to Flesh and Blood, is to witness forbearance in full view. It is to give pause to that which we feed on and to allow it to be fed for a time. It is to become nourishment for that which grants us our lives. It is to be on the receiving end of Death’s dominion rather than his supposed surrogate. This is the recipe we might prepare for Them, that we may be cooked, reduced and distilled in their crucible.

If Flesh and Blood in their endless incarnations are some of our earliest ancestors, then Hunger and Thirst are right there alongside them, requiring our reverence and our refrain. They are both the appearance of limits in our midst and our manner of honoring life. They are the roots and the fruits of all that constituted survival for our Old Ones. Likewise, language faithfully leads us by the ear, by the tongue, revealing to us how we might bear them in mind, how to carry them in our days

so that no one

goes

unfed.

Finally, in the bonehouse of the fast, with devoted allies and kin bearing witness, you sit prostrate on the platform of your dying days. Withered and worn, you raise the Gods to your mouth, pausing for prayer, the tears blessing the broth, the broth blessing the body, and a whisper:

Try as you may, you will forget this.

So, try as you might

to remember

this moment.

[1] Machado, Antonio. Times Alone : Selected Poems of Antonio Machado. , Translated by Robert Bly, 1st ed, Wesleyan University Press ; Distributed by Harper & Row, 1983. p 111

[2] “Fast” Barnhart, Robert K., and Sol Steinmetz. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. H.W. Wilson Co., 1988. p 317

[3] Somé, Malidoma Patrice. Of Water and the Spirit : Ritual, Magic, and Initiation in the Life of an African Shaman. Putnam, 1994. p 205

[4] “Fast” Barnhart, Robert K., and Sol Steinmetz. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. H.W. Wilson Co., 1988. p 317