Eldering in the Age of Consumption

What does it mean to be elder in today’s world?

Sharon Blackie

That question inevitably leads me to the related subject of death and dying. As always, when I think about these issues, I’m informed by the native wisdom and mythology of my Celtic roots.

I’d like to begin by sharing a short section from my book, If Women Rose Rooted, and then hear from Stephen Jenkinson, writer, author, and the founder of the Orphan Wisdom School in Canada:

…a man returned from hunting on Beinn Bhric one day when he heard a sound like the cracking of two rocks against each other. At the base of a large stone by the road, he found a woman with a green shawl around her shoulders. The woman, clearly a Glastaig, held a deer shank in each hand and constantly struck them together. He asked her what she was doing, but she cried only over and over again, “Since the forest was burned! Since the forest was burned!” And she kept repeating this refrain for as long as he could hear her.

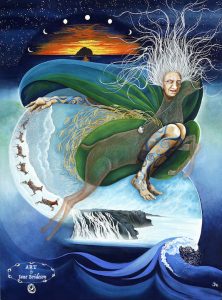

Here the Cailleach mourns the cutting of the forest. Here she mourns the loss of her deer. Here perhaps she mourns the coming of the road, the coming of Man, and of progress. Here, she seems to have been dethroned, deprived of her power to protect.

The elder, fully embedded in and belonging to her place, is fierce in her protection of it. Love and respect your place, she will tell you, for there is a strong argument that you begin to love the whole—not just a pretty idea of Earth, but the complex thorny reality of it—by learning to fully love your own part. We engage in a meaningful way with our current environmental crisis by starting with a place that we call home so that, in whatever ways are open to us, we can take responsibility for and help to protect the land that we occupy. The land which in a sense we personify.

In modern Western society, we want to preserve everything and we want to live forever. We wage war on old age and write songs about being forever young. Because death is seen as no more, no less than the end of the line—something to be held off and resisted—we live in constant fear of it.

But to the Celts, death was inextricably intertwined with life. Every month the moon died and was reborn. Every winter the Sun died and was reborn. The tide came in and the tide receded. To think that you could avoid these natural cycles was not only unthinkable but undesirable. Out of all the dying, something precious and new is always born. Unending transformation, the greatest of all the gifts the Earth offers us, life in death and death in life. It’s the secret that’s contained in the Grail, in the ancient cauldron of rebirth.

Perhaps more than anything, to become elder is to be comfortable with your place in the world, finally to have understood where all of your various journeys have been leading you, to understand your gifts as well as your limitations, and to tightly focus those gifts on service to the earth and to community. To become the elder who can express her wrath rather than her rage and warn of the direct consequences of ignoring it is to have stepped fully into your own power as a woman. To become elder is to have found the courage to reclaim the moral authority which we once lost. That reclaiming takes courage because women have always been trained so very well to be afraid, and it isn’t always our impotence which makes us most afraid. Sometimes it’s our power. We’re not accustomed to it and so we fear its consequences.

Perhaps more than anything, to become elder is to be comfortable with your place in the world, finally to have understood where all of your various journeys have been leading you, to understand your gifts as well as your limitations, and to tightly focus those gifts on service to the earth and to community. To become the elder who can express her wrath rather than her rage and warn of the direct consequences of ignoring it is to have stepped fully into your own power as a woman. To become elder is to have found the courage to reclaim the moral authority which we once lost. That reclaiming takes courage because women have always been trained so very well to be afraid, and it isn’t always our impotence which makes us most afraid. Sometimes it’s our power. We’re not accustomed to it and so we fear its consequences.

To step into your power means to trust yourself, your instincts, and your intuition. To let the fear go and the shame and tell the stories which need to be told.

Stephen Jenkinson

Elder really first and foremost should be a verb and not a noun or an adjective, which is to say, it’s something that’s done.

‘Eldering’ now is kind of gone without a trace. I don’t mean that the work is not undertaken, but it’s fitful and it’s scarred and it’s wounded and it’s deeply not sought by people in their middle age or in their young age as a rule.

The principal job of the elder in my lifetime, I think, is the willingness to not prevail, to not succeed, to not win, to not be victorious, but instead to have futility visited upon oneself with some frequency, to take upon oneself all the integers of limit which are human. They’re not indications of some kind of personal failure. I’m saying that the principal job of an elder in a culture addicted to competence—like mine is—is a willingness to ebb and then to end.

In a culture like ours, so unsure of itself, so without a shared understanding of life for its people, there are subtle, enduring consequences that look like personal inadequacy, failure of will, inability or unwillingness to live deeply. But what I’ve seen over twenty five years of working with people convinces me that these problems or struggles are not bad psychology, worse parenting or lousy personality development.

What we suffer from most is culture failure, amnesia of ancestry and deep family story, and phantom or sham rites of passage with no instruction on how to live with each other or with the world around us or with our dead or with our history.

So elders might take upon themselves the job of being everything that the worrisome and debilitated culture would rather not know about or see.

They are fundamental cultural workers if you understand culture to be the willingness to live within the limits that your home place dictates. If that’s what cultured people are—and it seems to me that’s what they are—then the elders are to be found at the absolute edge of what the culture should be doing.

Instead, what we have is a lot of elders being put into chronic care facilities—one of the things that culture shouldn’t be doing.

Sharon | To pick up on that question of elders reinstating limits, I think if I may go back to my example of the Cailleach, the old woman, who is one of our preeminent elders in the Irish and Scottish traditions, that’s kind of what she’s doing, which is why I think she’s such an interesting character for the times. She is saying to the hunters, “You may not take all of the stags. You may not take the pregnant hinds. You may not cut down the forest.” She kind of stands there as some guardian and protector of the land, which again in these times of ecological crisis is something that is very interesting to me.

In your book, Die Wise, you say that dying is about living with meaning. How does that tie into your concept of elderhood?

Stephen | North America is grief-illiterate in the extreme, and that means that people tend to die unknowing and uncertain about their dying, and this characterizes their dying time. Which is to say then that no matter how old they were, they tended not to die as exemplars of the elder function but in a way that was so banal in that the spectacle was all about keeping dying at bay, and when that ultimately failed, it was a kind of low-grade misery that attended most of them, to be frank.

North Americans come to their dying as an insult to their limitless potential. You can see where they got that idea from; they lived their lives in an elder-free zone where ‘limit’ was another thing to be defeated—to be sneered at. You get the right running shoes and the right t-shirt, and you can defy any limit. Go to the right weekend seminar or the right school or whatever, and you can defeat any limit. You can only hold onto that vision of personal heroism in the absence of an elderhood that not only pleads with you to see otherwise, but in fact enforces your own understanding of your limits upon you and calls that a gift.

Sharon | We don’t know how to be in the presence of death, literally to be. How do you think we can get better at that?

Stephen | It’s not really a question as so many in the North talk about it, of how to ‘befriend your death,’ how to ‘get comfortable’ with your death and all the rest. If death is an undomesticated, unhousebroken, wild thing, then the idea of you getting comfortable with it is totally uncalled for.

It’s really a question of the quality of approach. You could say that it might be a sane approach to death to craft and cultivate a kind of emotional and cultural spirit-based approach. One of the things I’ve tried to do for years and ultimately tried to put down in Die Wise was a language wherein the realities of dying would appear. Not be thwarted, not be assuaged, but appear, and try to speak the God-talk of death, or the death-talk of God, whichever you’d prefer.

For us to learn a language wherein the realities of death come to call, and to do so from a very early age, to be exposed to the language of death from a very early age, is in the realm of restorative measures.

Death is a given proposition. This is true, of course, horticulturally and in every other way it can be understood. So it’s a spiritual reality, dying, and it’s life-giving powers are absolutely undeniable and non-negotiable. Because when you banish dying and death and endings of all kinds from the language, you are in a chronically consumptive way of life that can’t even find a way of stopping.

From Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanity and Soul

“Grief is not a feeling it is a capacity. It is not something that disables you, we are not on the receiving end of grief we are on the practising end of grief.”

“Dying is active. Dying is not what happens to you. Dying is what you do. Dying.”

“We should be able to tell the difference between dying and being killed.”

About the Images

About the Images

Jane Brideson has been creating Sacred Art since 1980’s. She lives in an old cottage in rural Ireland where she is inspired by the landscape, Irish mythology, and folklore. She is currently on a creative journey with The Cailleach.

You can find Jane’s original paintings, art cards and prints on her Facebook page—Art of Jane Brideson SHOP—and on several pages on her blog—The Ever-living Ones.