Hope Leans Forward | The Body as Grounded Wisdom

The body is our house—and how we live in it and where we

occupy it are uniquely ours, as well as being part of the common

human experience. The body is a treasure trove and an exquisite

vehicle for our practice of waking up and being with what is.

—Jill Satterfield

My grandmother, Lillian, like my mother, was a domestic and tough, but she also had a tender side. I absorbed her toughness more than her tenderness, even though I admired her tender side. When they came, the tender moments took me by surprise, and I cherished them. We had a ritual every week where she would get out the foot basin and the Wray & Nephew overproof white rum. My job was to wash and massage her feet with the rum. She believed white rum would cure her debilitating arthritis, and I felt special, being asked and sharing the time.

Her feet were muscled, boxer-like and built, evidence of a hard life of little ease. At that time, she was well into her seventies, youthful by today’s standards, but back then, she was worn out, nearing the end of her life. Consciously or not, I absorbed many messages from this ritual. Two stand out. First, it’s exhausting to be a Black woman; it runs your body into the ground. Second, self-care is essential, indispensable when life is hard. She deserved, she earned, this moment to care for herself and for her body.

This memory lingered in me when decades later, following an intuitive sense that I needed to care for myself in a different and unaccustomed way, I began studying Kundalini yoga. My work was punishing my spirit and my body, and I needed to find a way out of the mess. I had worked myself into uterine fibroid tumors that eventually contributed to several miscarriages. While I received medical treatment, there was no safe place for me to talk about what was happening to my body. I joined a support group for women who had experienced miscarriages, but I felt isolated as the only Black person in the group.

To heal myself from the pain, I created rituals of healing, much like my grandmother did with me. I attended retreats for women who had experienced miscarriage. I lit candles. I prayed. I read books on loss and grief. Yet all this and more couldn’t dislodge the grief that had me like a straitjacket. It wasn’t until I traveled to Japan on the eighty-eight-temple pilgrimage of Shikoku that I began to heal, an experience I described in my first book, The Road That Teaches: Lessons in Transformation through Travel.

Our pilgrimage began in Osaka, and we took the high-speed train to Mount Koya, or Kōya-san, a World Heritage Site and the birthplace of Kobo Daishi, the founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism. The pilgrim officially begins at the temple gate at Koya as a symbolic act of commitment. Passing through the gate, the pilgrim takes a vow to complete the pilgrimage, not just for themselves but for the benefit of all beings. With moss-covered rocks, the scent of incense, the sound of temple bells and fast-moving water down forested hillsides, Mount Koya is a “thin place,” where the material and spiritual world meet.

As I entered the graveyard and passed through the temple gate, I bowed. The cemetery was partly dedicated to Jizo Bodhisattva, the Japanese deity said to aid pregnant women and travelers. Jizo is the caretaker of deceased infants and children, including fetuses lost to miscarriage and abortion. Hundreds of stone statues of Jizo line the cemetery stone walls. Some wear handsewn capes and hats, others stand atop mossy rocks, and still others receive a love note written in longing and loss. A damp teddy bear, a bouquet of faded flowers, yet another story of loss and love.

For years after the miscarriages, I felt barren and broken by the loss, shame, and guilt. There was a ragged, dispossessed part of me that I couldn’t shake. Here in the cold spring dampness of Kōya-san, my loss and grief were acknowledged and shared, not by a handful of people sitting across a table in the basement of a hospital support group, but openly by a culture and a people. I sensed that those in the cemetery around me understood and, unlike the support group, made space for the grieving to be and to breathe. The Japanese people recognized and honored the grief of miscarriage and abortion through this cemetery and these healing rituals, which said to me, What happened to you happened to us. What you’ve done, we’ve done. You are loved here. You can heal here. All of you is accepted, loved here.

The loss from the miscarriages is still there, though less so; less chokingly devastating, but there. Looking back now, I realize that in some ways, the miscarriages were fueled by fear of further loss, of the uncertainty and fragility of relationships that held me back from loving and being loved. I kept second-guessing myself with questions: Was it my unrelenting drive to “succeed”? Was it the running from poverty and toward a legal career? Was it the years of weight training and intense exercise that had eventually molded my body into an impenetrable shape? The one thing I did know was that the healing I was seeking wasn’t in the support groups with people comparing and one-upping their loss. The beginning of my healing started in a very unlikely place, halfway around the world in a cold, damp cemetery in Japan, where the collective grief was free to breathe and be held by everyone. With all this, I arrived at my first Kundalini yoga class: tough-minded and tough-bodied.

I started studying and practicing Kundalini yoga at about the same time I began studying meditation in the Plum Village tradition. Yoga and meditation were part of my healing process after a surgery for the uterine fibroid tumors, after my painfully short first marriage, and while pinned beneath the weight of my Big and Important Job as a lawyer-lobbyist.

As I began to practice yoga, one of my first realizations was that my breath and body were frozen and rigid, like a block of ice. I could barely turn my spine from left to right. My fingers dangled a couple of feet away from the ground as I folded my body forward, my hamstrings screaming with tension. Most shockingly, I couldn’t feel my breath.

My years of living an intellectual, success-driven life set me up for intellectual breathing. I was largely in my head, cut off from the wisdom of my body. My breathing was frozen. I was so focused on “getting there” as opposed to “being there,” and had spent so much time trying to outrun poverty and prove my own worthiness to myself and others that I had forgotten how to breathe. My breath, mostly in my upper chest, was shallow, and I recruited the secondary respiratory muscles of the neck, upper chest, and shoulders instead of the primary respiratory organ of the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and the intercostal muscles between the ribs. I had forgotten how to breathe with my whole body.

In studying yoga, I recognized and acknowledged patterns from decades of living remotely in my body. In law school, I studied torts, evidence, commercial law, but I learned nothing about my body, the breath. And years of working hunched over a computer left me nearly inflexible in body and spirit. Though breathing fully and completely lies at the very center of life, I was stuck in a shallow pattern that mirrored my stressful life. With Kundalini yoga, I set out to reclaim my breath and my body.

Before I began Kundalini yoga, I experienced chronic pain in my jaw, upper back and shoulders, and sides of my neck from poor breathing and a habit of bracing myself, which even affected my mood. Unconsciously clenching muscles in the anal sphincter affected my back and shoulders. I was hyper-vigilant and impatient with a nasty edginess. Even today, when I have a flash of impatience, I still catch myself and notice that my breathing tracks the feeling in my body. I feel my breath weak and uneasy.

After my return from Japan, I began reading the books of Judith Hanson Lasater and Donna Farhi, long-time yoga teachers, and then took breathing-focused classes with them. In The Breathing Book, Farhi points to several important characteristics of “free breathing,” which helped me understand the crucial, essential link between the mind, the body, and the breath. It was time to practice, even though I had plenty of resistance and plenty of skepticism. I’d lie on the floor with my knees bent or resting the back of my knees on the edge of a chair and listen to myself breathe. I felt dumb, like “This is a total waste of time.” I thought, “I could be squatting or deadlifting weights. I could be walking seven or eight miles, uphill. What am I doing here?”

I’d force myself to lie there being still, waiting for something, anything to happen, waiting for a signal. I stuck with it, and after a couple of weeks of this “do nothing” breathing exercise, one day I felt something. It was my breath but not in my chest and shoulders. I felt it at my reproductive organs and below the navel. It was like my body was opening and closing to the rhythm of my in- and out-breath. Oscillating, at first the breath was moving my tailbone and then rolling upward and outward to my shoulders and hands and then downward and inward to my legs and feet. Like boneless seaweed, the breath moved higher and lower, left and right, circular and in, multidirectional, then becoming calm and effortless. Through quiet attention, patience, and perseverance, this bruised and battered part of my body was beginning to move in freedom and harmony.

Slowly, incredibly slowly, I was being invited to trust and allow the breath to emerge and to release naturally. As I practiced this “do nothing” breathing, these words came to me:

Allowing ease and release

Allowing body to soften

Allowing breath to know ease

Allowing kindness

Allowing in-breath to meet the out-breath

Allowing pause between the in- and out-breath

Allowing lungs to be free

Allowing belly to be free

Allowing the heart to be free

Rise

Fall

In

Out

Deep

Slow

Breath.

As I invited the breath, I was being invited to inquiry, not only about my body, but also about my hard-driving life, my values. As I began with this foundational breath and body awareness practice, I retrained how I was breathing. And as I did, a lot of my chronic neck and upper-back pain was alleviated. But more importantly, through the breath, the real me—the vital me, the whole me—was rediscovered. I had found a different kind of intellect, a wisdom from inside my body that felt whole and right.

* * *

“Do nothing” breathing is now one of my most important rituals and I offer it to individuals in my coaching and leadership work, as well as to groups on retreat. Several years ago, I was invited to open the annual conference of Spiritual Directors International with my dear friend Karen Erlichman, and we offered a version of the “do nothing” breathing. The grand ballroom was packed with maybe six hundred people all practicing the breath I stumbled upon at the height of disconnect from my body. Most people were standing with their hands on their belly, breathing. Some people were laid out on the stage flat on their back, eyes closed, following this essential breath back, way back to an essential part of themselves. Still others sat in chairs, gently swaying from side to side. It was beautiful. Here’s what we did:

“Do Nothing” Breath Inquiry Practice

Choose what’s best for your body to sit, stand, or lie down, and allow yourself to get in a comfortable position.

- Allow your eyes to be open or closed. Notice what feels most comfortable.

- Notice the shape of your body without judging yourself.

- Feel your feet on the floor if standing.

- Feel your legs, hips, torso, arms, chest, face.

- Allow your spine to relax, and become aware of the back, sides, and front of the body.

- Bring your attention to your breathing.

- Feel the breath come in and go out.

- Notice and feel the in-breath.

- Notice the pause between the in- and the out-breath.

- Notice and feel the out-breath.

- Feel the belly rise and fall.

- Practice gently bringing your attention back to the sensation of breathing; feel the rise and fall of your belly.

- Feel yourself breathing in and out.

- Imagine your body like boneless seaweed with roots, grounded yet totally free.

- Notice how you’re feeling physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually.

- Take a moment to sense your breathing and ask yourself, “Where do I feel my breathing?” and simply wait.

- Return to the question over and over: “Where do I feel my breathing?” Let whatever perceptions you have be here without editing them. Don’t discount tiny movements.

- Place one hand on the belly and the other at the chest or any place on your body, if that’s appropriate for you, and feel the movement of the hand at the belly and at the chest or that part of your body.

- Ask yourself, “What does my breath feel like?” and simply wait without judging yourself. Gently keep returning to this question: “What does my breath feel like?” Become aware of words or images that might arise to describe your breath. Again, let whatever perceptions you have be here without editing them.

- Return your attention to the body and mind, gathering an impression of how you are doing at this moment. There is no need to change or edit this moment.

- When you are ready, stretch gently to close this practice and notice how you feel.

My grandmother had little chance to practice “do nothing” breathing. Yet our ritual of washing her feet with white rum taught me that you’ve got to make doing nothing a major priority, no matter what. And I do and will continue to practice that for her now.

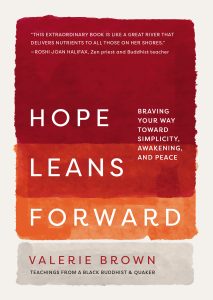

Excerpted with kind permission from:

Hope Leans Forward

Hope Leans Forward

Braving Your Way toward Simplicity, Awakening, and Peace

by Valerie Brown

PUBLISHER Broadleaf Books

PAGES 275

PUBLICATION DATE November 8, 2022

Recipient, Nautilus 2023 Gold Award for Eastern Spirituality