Cinderella Story

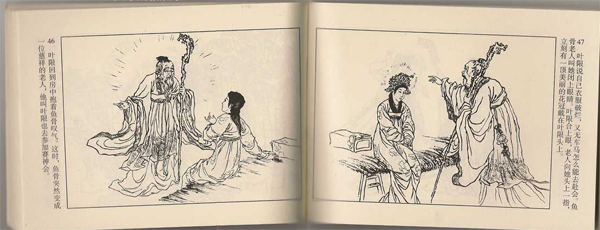

It is early morning, still dark. You awaken from a glowing sleep and clutch the last shreds of warmth to your thin body. Soon, you will get up and go down to the kitchen, which is like a damp tomb. You will sit by the fireplace, in the ashes of your dreams. You will not despair.

You will not despair, because there is a Mother you thought beyond reach who brings a love beyond imagining. She transforms golden vegetal life into a carriage to bear you out of the mire and into the glory of the world, into the ring of the dance.

You will not despair, because there is the promise of romance. A prince filled with quiet strength who offers his hand to you, and secretes iron and its mineral allies into your bloodstream, and re-kindles your sacred fire.

You will not despair, because of who you are, and are becoming.

Intelligent women are suspicious of this story. They feel their daughters should not imagine the release from torment will be through a benign godmother appearing out of the starry blue; nor – especially, not this – that their soul will be saved by some young buck waltzing up to the palace ballroom, and sweeping them off their feet. While the values informing this rejection are reasonable, the narrative spell here contains teaching secrets.

Some stories are found almost everywhere in the world, in cultures remote from each other, and this suggests certain deep patterns in the human psyche. Surveys of people’s most cherished childhood stories show these universal stories are the ones we tend to love best and the Cinderella story is the most universal of all.

The prevalent theme is typically that the wellbeing of a maiden, naturally pure and gracious, is compromised by the malice of an evil ‘other’ (she is imprisoned, or enslaved, or enchanted into a death-like sleep) and has to be released from her trance of helplessness.

This tale belongs firmly in the feminine domain. It has not been censored or interfered with by men, and always has been and remains an instruction manual for girls. It actually flies quite cleverly under the radar of ‘inquisitorial’ masculine attention; after all, it it appears on the surface that the ‘baddies’ are female, and that ‘it takes a man’, ultimately, to set everything to rights.

Yet, there are two vital points here. One is that such stories were never meant to be interpreted literally. They are depth-charges, designed to float down below the surface of our consciousness and detonate in our metaphorical mind, shifting patterns of despair. The other is that the colorful cast of ‘players’ in mythical stories is purely illustrative. There is only ever one character, and it is the singular you.

The ‘ugly’ sisters and ‘impostor’ mother model the daughter’s own agents of diminishment. The fairy godmother is her own kindly and resourceful larger ‘self’. The dynamic masculine is a ‘sleeper’ in her soul awaiting discovery and awakening. The story is a guidebook for the sacred marriage of all the discrete instruments in her, and becoming ‘virgin’. That is, poised and complete in herself, and self-regenerating.

Entire in herself. Actual men optional.

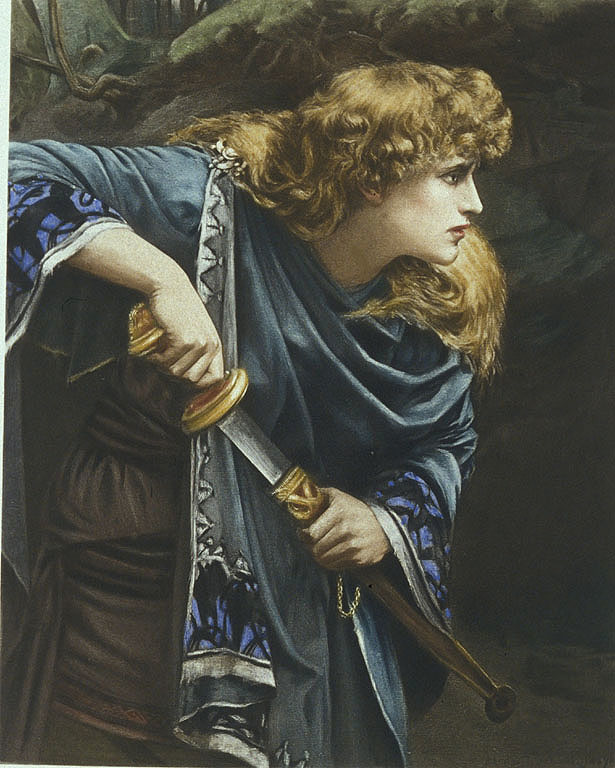

The irrepressible Imogen, in Shakespeare’s ‘Cymbeline’, affords us a picture similar in all its vital respects. The poet, Ted Hughes defines her as “the soul of England”. The deep feminine is fully integrated in her, so nothing daunts or overwhelms her (including the malign designs of the step-mother, who also looms large in this story). And, in the final part of the play, she moves out from her ‘sleep-death’ in masculine guise as, a warrior, conjoined with that most rigid of male-dominance constructs, the Roman army. She releases this identity only when balance is restored in her soul and her relationships. Then, the whole realm, in danger of becoming a Grail-deprived wasteland, is restored to health.

The irrepressible Imogen, in Shakespeare’s ‘Cymbeline’, affords us a picture similar in all its vital respects. The poet, Ted Hughes defines her as “the soul of England”. The deep feminine is fully integrated in her, so nothing daunts or overwhelms her (including the malign designs of the step-mother, who also looms large in this story). And, in the final part of the play, she moves out from her ‘sleep-death’ in masculine guise as, a warrior, conjoined with that most rigid of male-dominance constructs, the Roman army. She releases this identity only when balance is restored in her soul and her relationships. Then, the whole realm, in danger of becoming a Grail-deprived wasteland, is restored to health.

This is the resolution of the despair of an earlier play, King Lear, in which the eponymous ruler comes to his senses too late to save anyone at all. His virtuous daughter dies, as do the two ‘ugly’ sisters – and so does he. Shakespeare’s audiences deplored this ending, and their offended instincts were correct. This is not how things end in the true mythos of these isles.

‘Lear’, in Celtic lore, is ‘Lir’, god of the ocean, and his daughter, Cordelia (Cor-de-Lir), is a divinity in her own right. She represents his ‘maiden’ heart (as Miranda does for Prospero in The Tempest) and governs spring flowering and renaissance. In these final ‘Romance’ plays, we are shown over and again it’s impossible to negate or suppress this regenerative daughter.

Her spirit is perennial, and her luminous presence dispels the miasma of our social malaise.

There are a surprising number of young women like this in Shakespeare’s plays and he makes plain, in his last dramas, that it is they who pose the right questions, and are the embodied answers, to all the fractured relations in family and realm. After Imogen, in the gnostic fable of Pericles, comes Marina, the resilient daughter who negotiates horrific schisms, then glides untouchably through the ‘mean streets’ and seedy culture of a sea-port, moving eventually to heal her despondent father, and re-unite him with her long-estranged mother. After Marina, in The Winter’s Tale, comes the ‘lost’ maiden, Perdita, who finds her innocent yet utterly assured way to repair the rifts within her kin, and between the states ruled by alienated fathers. Finally, after Perdita, comes that epitome of grace and compassionate action, Miranda, who moves out ultimately from the magical island milieu of The Tempest – and from the protective ambience of a flawed father – again, to re-unite warring families and city states.

In each case, these plays are variations on the same message: that it is the spirit of the ‘daughter’ that addresses and rectifies the faults of the ‘father’. Also notable, in each case, is the daughter does not disrespect the father but, nevertheless, proceeds with absolute determination to effect what she knows in her heart is necessary (for example, in the lively flower festival scene which shifts The Winter’s Tale into a different gear, Perdita listens to the cogent masculine arguments for the ‘rightness’ of interfering with natural patterning – and rejects them decisively).

The archetype that corresponds most nearly with this spirit is that of Artemis, the classical protector of the irrepressible nature of the ‘maiden’. While the other leading female players in Greek mythology, Athena, Aphrodite and Hera are submitting themselves to the masculine judgement of Paris in the Miss Olympus beauty contest, Artemis is running free in the forest, challenging any man to set boundaries on her – or to fracture those she has established herself around her world (as Actaeon, among others, discovers to his chagrin when he dares to spy on her bathing). That Shakespeare acknowledged her vital importance is without doubt: the plays are suffused with her presence and iconography. In her latter-day Roman incarnation of Diana, she is referenced directly in more than half of them and, even where not, it is still her associated lunar and wild-wood domains that often play critical roles in the drama.

The archetype that corresponds most nearly with this spirit is that of Artemis, the classical protector of the irrepressible nature of the ‘maiden’. While the other leading female players in Greek mythology, Athena, Aphrodite and Hera are submitting themselves to the masculine judgement of Paris in the Miss Olympus beauty contest, Artemis is running free in the forest, challenging any man to set boundaries on her – or to fracture those she has established herself around her world (as Actaeon, among others, discovers to his chagrin when he dares to spy on her bathing). That Shakespeare acknowledged her vital importance is without doubt: the plays are suffused with her presence and iconography. In her latter-day Roman incarnation of Diana, she is referenced directly in more than half of them and, even where not, it is still her associated lunar and wild-wood domains that often play critical roles in the drama.

As we might expect, given the timeless importance of Artemisian qualities, particularly for an age where rigid and outworn structures are crumbling, this archetype has also surfaced in key figures in modern culture. A prime example is Katniss, from The Hunger Games, whose father predicts she will surmount all hunger if she amasses the courage to “find herself” truly, which she does. Katniss, like our Shakespearean heroines, engages with the world of men and their intrigues, but is neither defined nor defiled by them. In the end, it is her clear perception, her courage, that saves the beleaguered populace; her arrow that pierces to the heart of the malaise.

Thankfully, it is not only in fantasy that such figures are emerging and stepping into leadership. Among many others, we have Malala Yousafzai taking her brave stand against the Taliban, Emma Gonzalez challenging rabid gun enthusiasts in Florida, Greta Thunberg raising the stakes in the climate control debate, Autumn Peltier guarding the sanctity of native waters. Each of these arriving on the scene, rather enchantingly, not as seasoned political schemers, but as raw ‘forces of nature’. Their heartfelt actions defining our truest hope.

Michael – a beautiful perspective of feminine strength and courage fully awoken, without the bloke bending over breathing heavily in the maiden’s general direction. Love this. Thank you.

Nice to see your writing out in the world – ever blessed.

Shine on crazy diamond.