Chasing Solitude | Pilgrimage to the Dead Sea

Featured image | by Keith Chan

The temperature skyrockets as soon as the first rays of sunlight creep over the horizon.

My skin feels as though it might crack under the relentless heat like a patchwork of asphalt in summer, longing for moisture and relief. We hike for hours under the merciless sun. Our train of seventeen hikers looks like a line of ants fleeing an impending storm, but I know there is no chance of rain for the next several weeks at least. We have seen no plants or wildlife for several miles, and the only sign of life other than ourselves has been small beetles and lizards that scurry across the ground. Dust kicked up by hiking boots gets swept up by the scorching wind and blown back into eyes and open mouths. I take a long drink from my water bottle, hoping we reach our destination soon so that I can rest my aching feet.

My legs burn as we approach the crest of a rocky hill. I raise a hand to block the blinding light and look at the valley below. We all stop to take in the scene. A small dirt road stretches for miles back in the direction we came from. Ahead, mountains form walls on all sides and below us, the Dead Sea makes a shining, silver crater in the sand. That pool of water is our destination. A wave of relief washes over my body.

I take another drink of water and let the droplets wash paths from the corners of my mouth down my neck before adjusting my backpack. Amir, our guide, pats my shoulder, “Are you alright?” I squint at him, making out his crooked smile and curly hair hidden under the shadow of his bucket hat. I am glad to see he is sweating just as much as me, assuaging my fear that I must be out of shape.

I nod. “I’m ready to go swimming.”

He chuckles. “That makes both of us.”

It’s December of 2019, just a couple months before the Covid pandemic explodes across the globe.

Amir and I only met a week ago, when our group of American college students landed in Tel Aviv for a two-week, cross-cultural trip in Israel. He and I have had incredibly deep conversations on the bus and during debriefs. The whole objective of this trip is for college students to learn about the foundation of their faith; to encounter God in the Holy Land. The land that is biblical. Sacred. There is a mutual appreciation between Amir and me. I listen to his long speeches about history and culture with devoted attention. In turn, he is grateful that someone will listen. Amir can tell I am eager to learn, and he provides answers with the same level of nuance that I ask my questions.

I follow him down the rocky hill, the promise of cool water pulling me forward. It takes another twenty minutes but eventually we reach a small cluster of buildings along the shore. Amir goes inside the largest building, telling the rest of us to wait outside. He is paying the entry fee and assessing the arrangements they have for our group. I kick at the coarse gravel where we stand in the parking lot, where tour busses are parked in symmetrical rows. Amir reemerges and motions us inside; air conditioning brings a sigh of relief from everyone.

The inside of this building is stark white with acrylic shelves spread across polished floors. Stacks of products are set up in rows, promising things like glowing skin or softer hair using minerals harvested from the Dead Sea. Precious resources are packaged to be bought and sold for beauty, marketed at tourists searching for some kind of tangible result from their experience.

A woman calls to our group, asking us to step up to the counter. I am amused, imagining what she must think of us. A fine layer of dirt covers every part of our bodies. Sweat has cut clean lines through it, making strange mazes on our necks and down the sides of our faces. We leave brown tracks across the pristine floors as we approach her, and I can’t imagine how bad we must smell compared to the soft scent of salt and lavender that floats through the store.

She sighs and begins the speech she has undoubtedly recited a thousand times before, “Welcome to the Dead Sea.”

“As most of you probably know, this is a salt lake bordered by Jordan, Israel, and the West Bank. Right now, we are 430 meters below sea level; Earth’s lowest elevation on land.” She gestures to the room, “Here, we have a selection of Dead Sea cosmetics that you can use as you relax here. These products are made from materials gathered from the Dead Sea. We have a wide range of choices with minerals that are good for your skin and complexion. If you have any questions about them, please ask me. Women’s changing rooms are down the hall to the right, men’s are to the left. Enjoy your time at the beach.”

Ignoring the rows of cosmetics, I attempt to push the obvious evidence of exploitation out of my mind. I understand that I am also here as a tourist, but I clutch to the thought that maybe I am not like others. Abuse of a natural landscape is obvious to me as an environmental studies student, and I will not be participating in that. I change as quickly as I can and walk through the breezeway toward the beach.

The heat returns as soon as the sun touches my skin, making me sweat instantly. I find a few members of my hiking group who beat me to the shore and toss my bag on the ground next to theirs. We are giddy with excitement and run toward the sea, eager to experience one of the natural wonders of the world. Some people stop short of the water, yelping in pain at the large salt crystals on the shoreline jabbing the soles of their feet. I’m glad I chose to wear my sandals as I wade up to my knees.

I watch as the water lifts dirt from my skin and washes it away. The cool waves lap at my legs, beckoning me to go deeper. I trudge farther out until the water reaches my waist and then I slowly sit down like I’m about to take a seat in a chair. The density of the water holds me afloat with no need to paddle. Others do the same and squeal in amazement. I stretch out and float on my back and the sounds around me become distorted by water. Staring at the sky, I take a few deep breaths and then close my eyes.

I allow myself to float there for a moment, thankful for the chance to experience this place.

I feel the water below me, the extreme amount of salt making me buoyant. The sun spreads warmth across my stomach as the water keeps me cool. I taste salt so strong it is almost bitter on my tongue, and I grind the dirt I nearly swallowed on our hike between my back teeth. The wind creates small ripples, causing me to rise and fall with the waves.

My eyes open when I feel a tingle on my left elbow. I twist my arm around and look at a scrape I didn’t know was there. The salt stings as it sterilizes my cut. I rub my hand over it and my skin feels almost oily, saturated with healthy minerals from the water. I can understand why ancient peoples would flock to the Dead Sea for traditional remedies and beautification.

I watch my friends splash each other and then scream when the saltwater gets in their eyes. Looking past them, I see Amir sitting alone on the shore. My elbow is burning now, and I’d rather not get water splashed in my eyes too, so I decide to join him.

Amir is eating a bag of dried apricots and offers me one as I take a seat next to him. I bite through the sweet skin and taste the tart center. He clasps his hands and wraps his elbows around his bent knees. “What do you think?” he asks, in a thick accent that is more difficult to understand when he has an apricot tucked in his cheek.

“It’s beautiful,” I say, staring at the glimmering water.

He nods silently and sighs. Casually, he says, “I tried to swim across when I was little.”

I laugh in disbelief, “What?”

His pensive expression cracks into a smile. “That’s Jordan, right there on the other side,” he points at the mountains in the distance. “I thought it wasn’t that far.” He lets out a small laugh, “Don’t try it. There are waves in the middle. You’ll get stuck. It took me three hours to swim a hundred meters and back.”

“How old were you?” I ask.

“Eleven,” he says, and I laugh again, imagining a tiny Amir attempting to swim across the massive expanse in front of us. “I grew up not far from here,” he continues. “I did all kinds of crazy things like that.” He places a hand on the back of his head to keep his hat from blowing off in the wind.

“Wow,” I sigh. “That must have been incredible.”

He nods and points in the direction we hiked from, “I had my bar mitzvah maybe twenty minutes from here.” He faces the water again and stares at the horizon, “Stargazing here is the best. No lights. No distractions. The water stays warm at night and you just float.” I can tell he is picturing it. There is a long pause before he says, “It’s shrinking, you know.”

I look up at him, “I didn’t know that.”

He nods slowly and I can tell he’s deep in thought, “The water goes down five to eight meters every year. Fucking climate change.” Although he mumbles the last bit, I am startled. Even in our long conversations about difficult topics, I’ve never heard Amir swear. “Excuse me,” he quickly says, noticing the expression on my face. “I don’t mean to offend.”

“No, it’s okay,” I assure him, knowing I have said much worse over much less.

He looks back at the water, “Who knows how much longer this place has?” worded like a question, spoken like a statement.

“The Jordan River is…” he trails off, unsure of the English word. “Where the water comes from?” he looks at me, knowing I study these kinds of things.

I nod encouragingly, “We call that a tributary.”

He repeats, “Tributary. New word.” Amir pulls out his phone and types it into his notes. He shows it to me so that I will check his spelling. With my approval, he tucks his phone back into his pocket. “The Jordan River is its main tri-bu-tar-y,” he over-enunciates every syllable, “but now summer lasts two months longer than it used to; the river is drying up. More and more people are using the Jordan for water. Places like this–” he points to the buildings behind us, “they mine minerals from this place and use them for profit. It’s wrong.”

“I thought that was weird,” I agree, reflecting on our short experience inside and the lady trying to sell us expensive cosmetics. “Amir, if you think it’s wrong, why do you bring people here?” I ask gently, trying not to sound accusatory.

He shrugs, “It’s my job. I am a tour guide.”

I stare back out at the water, watching the rest of our group float together. Guilt builds inside of me. Are we part of the problem just by being here? The amount of jet fuel it took to get here, I know there is significant damage I have done. How naïve I was to think that simply avoiding the manufactured goods inside would offset my other actions. What other ways have I hurt this place I don’t even realize? I know that Amir is a tour guide and he’s right, this is part of his job. But he’s also a husband and a father. Who knows if the Dead Sea will still exist when his now two-year-old daughter is grown?

“I’m sorry that it’s disappearing,” I offer, unsure of what to say.

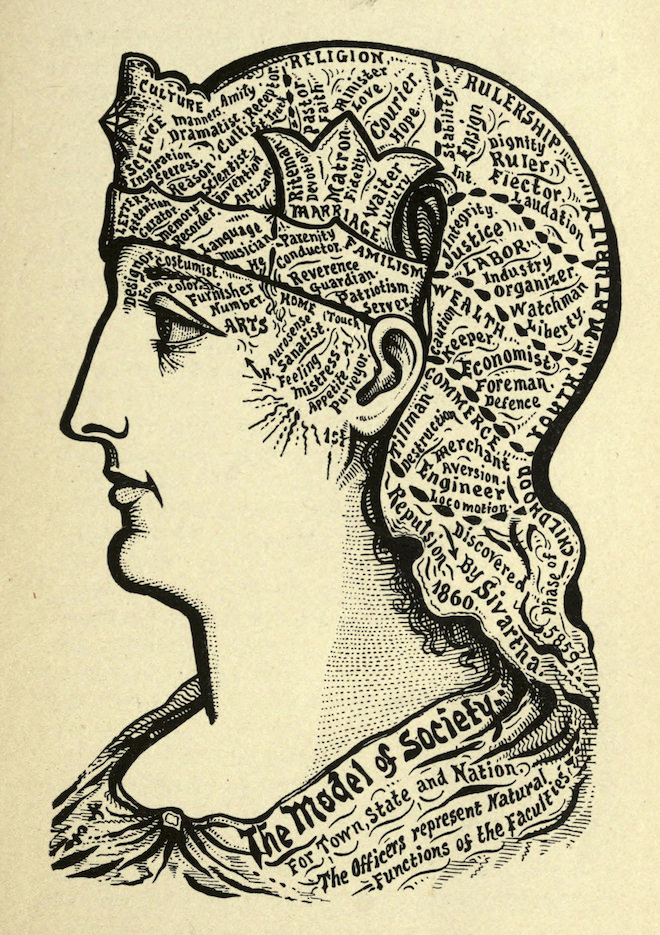

He shakes his head, “It happens with time, I guess.” He chews on another apricot, contemplating something. “But it’s more than just the fact that the water is disappearing. I’m worried that people won’t want to visit the Judaean Desert after it’s gone. They will just think there is nothing to see. But I want people to see this place. For me, the desert is highly spiritual. Because, when you’re here, it’s only you and the connection you make. There’s no voices, no colors, no smell; it’s just you and Creation. Look–” he gestures to the water and sand around us, “–Genesis all around you without intervening.”

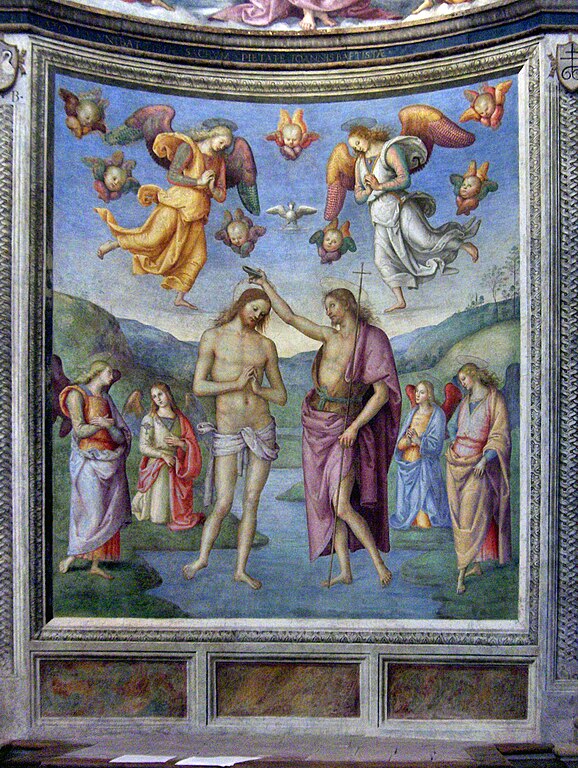

I look around and try to take in the expansive nature on all sides as Amir continues, “And if you think deeper, all the prophets in the Bible spent a long time in the desert.” He begins to list the ones he is familiar with, “Moses, Elijah, John the Baptist, Jesus when he was tempted by Satan; you can find it in all the monotheistic religions. Even Buddha spent time in the high desert of Nepal and Tibet.”

He takes a long pause before saying, “Something happens in this environment,” and he stares straight ahead at something I can’t see.

Another gust of wind stings my skin as it picks up sand. Amir clutches the wide brim of his hat.

We sit there for a long while in silence.

I understand what he means, something transformative does happen here. I felt it, floating in the water. The level of gratitude I experienced was like nothing I’ve ever known. With the movement of my body, my mind began to wander. I felt suddenly aware, like all of my senses were heightened. I imagined that, instead of being a few meters from the shore, I was in the middle of the ocean, floating freely wherever the current took me. A sense of freedom drifted over me—increasingly grateful that places like the Dead Sea exist. A place to simultaneously look outward and inward; where people can experience a natural wonder of the world and examine their place in it all.

I also know that this experience isn’t unique to me. The desert is a central image in Christian and Jewish tradition. It has figured importantly in the Western spiritual imagination—from the Hebrew peoples’ encounter with Yahweh in the Sinai Desert, to Jesus’s journey in the Judean wilderness, to the sudden uprooting of early Christian life in Egypt. The Judaean Desert functions as a metaphor for the deep unknowability of God, for the stillness, silence, and emptiness in which a meeting with the divine becomes possible.

These aren’t just ancient concepts. Many scholars argue that contemporary people are longing for more space, silence, and stillness in their lives, something captured symbolically and concretely by the vast horizons of the desert. There is a growing hunger for depth and meaning, for a connection with other human beings rooted in humility, reciprocity, and love. And there is a dawning awareness that meaningful engagement with others will require the kind of radical self-honesty and purity of heart that desert traditions have long cherished.

Such rich experiences and beliefs are what Amir is referring to when he speaks about the spirituality of the desert. There is a cultural, historical, and spiritual background to every aspect of life here. But there are only a few places that people want to visit that are so far from modern civilization. The Dead Sea and its neighbor, Masada, are the main attractions in the Judean Desert. But, as Amir said, the Dead Sea is drying up and there are rumors of Masada limiting its tourism to protect the environmental integrity of the landscape. I now feel the same fear Amir expressed and wonder, what will bring people to the desert?

I ask Amir that same question and he shakes his head, “People must want to discover it for themselves. You shouldn’t be manipulated into travelling here. People need to arrive with an open heart and mind. They need to be ready to learn whatever this landscape wants to teach them.”

I nod in agreement and turn to Amir, “So what has it taught you?”

He stares at the horizon again, pondering his answer. A gust stronger than the ones before suddenly catches Amir’s hat and rips it off his head. He jumps up to race down the beach after it. Before he takes off, he answers my question, “Hold onto your hat.” He laughs and then runs a few steps before calling over his shoulder, “And don’t try to swim to Jordan!”

A smirk presses my lips together as Amir jogs away, amused by his cleverness and ability to ask profound questions without ever answering them himself. Leaning back until I am resting on the ground, I breathe deep and close my eyes. There are no currents moving beneath me, but I feel a kind of shifting. Not the undulation of the waves, but something different—like breathing.

In the Old Testament, when the Israelites escaped their slavery in Egypt and began their pilgrimage to the Promised Land, the wilderness was called “vast and dreadful,” devoid of water, with scorpions and venomous snakes hiding in the shadows. But Yahweh guided them through the treacherous landscape for forty years. I examine the toll the desert has taken on my body—blisters on my feet, the heat of a sunburn wavering up off my shoulders, dry skin, cracked lips, lines at the corners of my eyes from squinting against the harsh sun—and cannot imagine spending four decades exposed to its brutality. But God acknowledged the barrenness of the desert and blessed the people with the miracle of manna and quail, taking the desiccated land and bringing them water out of stones. In this inhospitable place, the Israelites were made God’s chosen people and presented with the Law and Covenant. Deep in the desert, they experienced an intimacy with God that would be longed for and remembered for millennia.

I feel that movement again, that strange breathing in my spirit.

I sit up and gaze across the blinding glare of the water at the mountains in the distance. I pick at a salt crystal the size of a quarter in the sand, loosening it with my fingernails. The piece of salt crumbles once I drop it into my hand and roll it between my fingers.

The desert’s teachings are unique to everyone and everything. Amir mentioned the isolation that comes with going into the desert—the idea that there’s nothing around except you and the connection you make. I know there is a bridge there: my relationship with nature is tied so closely to my relationship with God. Standing atop a peak with the wind pulling my hair from its braid. Sitting on the shore of a river, watching the water glide over smooth stones. Hiking through the woods and gazing upward through the canopy toward the dappled sun. Biking over mountain trails with the roughness of the terrain vibrating through my handlebars. It’s places like this where I feel closest to my Maker. But why?

Definitive answers to these kinds of questions don’t exist, and Amir knows it.

It is said the biblical prophet John the Baptist wandered in the Judean Desert in the first century A.D., living off the land, eating locusts and wild honey, clothed in camel hair, reflecting desert traditions by living in humility and love. In his wandering, he fulfilled a 600-year-old prophecy by preaching and wading into the cool waters of the Jordan River to baptize Christ-followers, all while announcing the ministry of Jesus. I’m not conceited enough to believe that I am a twenty-first century John the Baptist, but if I were called into the desert to teach others about what the land has taught me, what would my message be?

A few days ago I asked Amir if he has ever thought about leaving Israel and raising his family somewhere else—Israel is constantly under public criticism from the rest of the world, often depicted as a violent land, filled with gunfire, bombings, terrorists, and religious radicals. He shook his head when he responded, “I’ve never wanted to leave. There is so much history here. This land is holy. It’s biblical.”

With this sacred view of the land Israelis occupy, there is also the reality that tourism is their highest source of income. It’s an industry that fuels the environmental degradation I’ve witnessed here. It promotes tourism at the cost of the environmental integrity of the planet. A pattern seen too often on many parts of the globe.

The tourism industry provides for Amir’s family and millions of other Israelis. It’s what allows me to be in Israel at all, to float in the Dead Sea, to touch the waters of the Jordan River.

I’m on a kind of pilgrimage of my own.

I’m removing the obstacles between myself and my Heavenly Father. Entering a place where I can reflect on my faith and examine my values. I’m forced to wrestle with the ambiguities and inconsistencies that come with spirituality. The degradation of the planet under a good and all-knowing God. In the emptiness of the desert, I am suddenly aware of its fullness: the burnt sand-colored mountains in the distance, the white glare off the surface of the water, heat on my skin, dust picked up in the wind, salt in the air, waves on the shore, and I take a single breath—expanding my lungs to their full capacity.

I’m alone in the desert, and I’m standing before God.