Birdsong as a Compass

The booming call of the Pheasant Coucal is soft and rhythmic on a calm, springtime afternoon.

I first noticed it in 2004, when I was eight years old. From the window of our old weatherboard house, I spotted the bird splayed out on top of the wire fence, calling out into the bushland: He has a streaked black head with a robust, downcurved beak, and he’s fanning his broad, intricately patterned wings and tail. He’s big – so big, I take him to be some kind of hawk or eagle. Is he stuck in the wire? Is he injured? Is he calling for help?

I first noticed it in 2004, when I was eight years old. From the window of our old weatherboard house, I spotted the bird splayed out on top of the wire fence, calling out into the bushland: He has a streaked black head with a robust, downcurved beak, and he’s fanning his broad, intricately patterned wings and tail. He’s big – so big, I take him to be some kind of hawk or eagle. Is he stuck in the wire? Is he injured? Is he calling for help?

I run down to the backyard to untangle him, but when his maroon eye clocks me, he simply glides away and disappears into the undergrowth. Later, I scan the pages of my bird guide for his identity. I find him nowhere near the birds-of-prey section, but rather in an odd place between the parrots and the cuckoos. The book describes: “a booming call during early summer mating season”. He wasn’t stuck – he was performing!

Over the next few years, this Coucal friend returns to his favourite stage every springtime, to fill the garden with his strange, subtle yet powerful frequency. I grow sensitive to his rhythm – to the changes in his plumage as he moults to wintertime.

But soon, I become aware that he’s performing to an empty forest – he’s the last of his kind in this remnant patch of bushland on the Northern edge of the expanding city of Sydney. One year, he too disappears, and no one takes his place. A sense of loneliness buds inside me.

This loneliness echoed through my teenage years. I remember feeling angsty, always angry at “the system”, with its fast cars and consumerism and shitty pop music. I hated how it stressed out my parents and weighed on our family. I hated how it drove species to extinction and pumped the atmosphere full of greenhouse gases.

But high school geography class taught me that all this was inevitable – that the global expansion of the industrial economy and consumer culture was the very meaning of “progress”.

So I chose to escape to another world: an island of my own imagining, in which people dwell in the hollows of huge trees painted with coloured beeswax, and live from the fruits of the forest, and make friends with the animals around them, and go on voyages to trade and celebrate with foreign-tongued peoples from afar. Giant Pheasant Coucals build nests in the vegetable gardens that the island folk plant in the massive boughs of the trees.

I drew innumerable maps of this island and sketched its inhabitants. But a sense of helpless anguish was never far beneath the surface. Every night for a year, I fell asleep listening to the music of The Cure, whose mix of whimsical pop and melancholic goth resonated with a weird little teenage boy who loved life but hated “reality”.

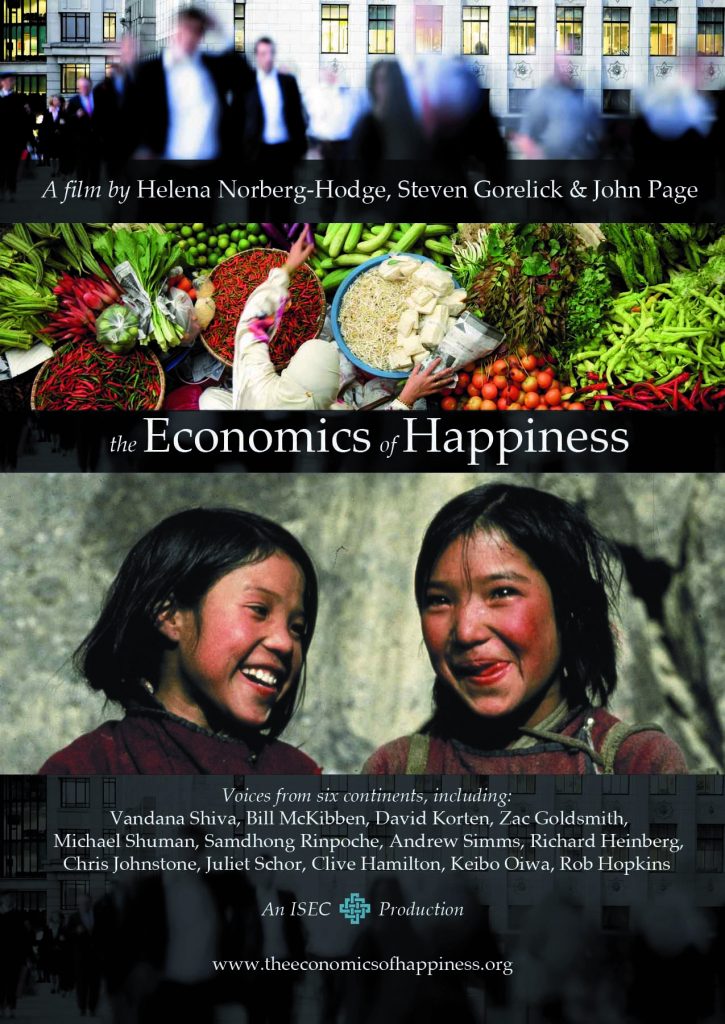

One evening, when I was fifteen, that reality cracked open. My friend’s mum (a hippy woman who fed me my first ever slice of seeded sourdough) took me to a public screening of the documentary The Economics of Happiness. The film railed against the conventional idea of “progress”, and revealed its skewed, neo-colonial ideological scaffolding. Through the lens of a remote community in a part of India I’d never heard of, it showed how corporate globalisation is a programme of economic engineering that is actually generating unemployment, poverty, conflict and depression, even as it chews up ecosystems and trashes the planet.

One evening, when I was fifteen, that reality cracked open. My friend’s mum (a hippy woman who fed me my first ever slice of seeded sourdough) took me to a public screening of the documentary The Economics of Happiness. The film railed against the conventional idea of “progress”, and revealed its skewed, neo-colonial ideological scaffolding. Through the lens of a remote community in a part of India I’d never heard of, it showed how corporate globalisation is a programme of economic engineering that is actually generating unemployment, poverty, conflict and depression, even as it chews up ecosystems and trashes the planet.

Believe it or not, this was like music to my ears. Finally, I was relieved of the crippling idea that human prosperity and ecological wellbeing are somehow separate, mutually exclusive goals. The film pointed to the shared roots of our social and ecological problems, laying out a way forward that helps on all fronts. It called this path “localisation”.

I’d never heard that word before, but somehow it made the world of sense to me. It meant growing food close to home, trading it at local markets with people with familiar names and faces. It meant allowing diverse cultures and individuals to follow their own dreams, unimpeded by the pressures of centralised profit-making. It meant rebuilding diversified farms connected to local, circular economies, in which the line between “wild” and “cultivated” was blurred.

This connection – between local economic revitalisation and cultural and biological diversification – was like the missing piece of the puzzle for me. It was a pragmatic policy framework; a roadmap to a world that looked more like my island, and less like cookie-cutter suburbia and big grey shopping malls. One that sounded less like Taylor Swift and more like Barn Swallows nesting in the eaves.

Thanks perhaps to my sensitivity to the weird and wonderful diversity of the bird world, this piece of the puzzle fell right into place. I realised that, by re-embedding our economies, our cultures and our spirits in local ecologies, the human world could one day be as beautiful, as salubrious, as intricately patterned as a Pheasant Coucal’s tail feather.

I left that film-screening a changed boy. I started volunteering at the nearby community garden, learning about composting and food-growing, and turning my obsessive mind to understanding localisation.

Now, I’m 24 years old and I haven’t changed all that much. I’m still obsessed with birds, I still listen to The Cure, and I’m still keenly learning about localisation. I even work for Helena Norberg-Hodge, the director of The Economics of Happiness and my teenage hero. We go on walks through the forest together, and she gets so excited when I tell her about the birds we hear.

Of course, it still saddens me deeply when I notice an absence where once there was a Brush Bronzewing, or a Rockwarbler, or a family of Yellow-tufted Honeyeaters. That loneliness never left. But now, I’m thankful I can feel it.

I’m thankful because its empty shape contours the place where the wider community of life should be. It therefore serves as an invaluable compass: to guide me through the confusion of ideology and pseudo-solutions, towards the only place where life – in all its wondrous diversity – can truly be cherished and nourished. It points the way forward: towards the local.