Big Lazy | Music for Unsettling Times

Cover Photo | Marco North

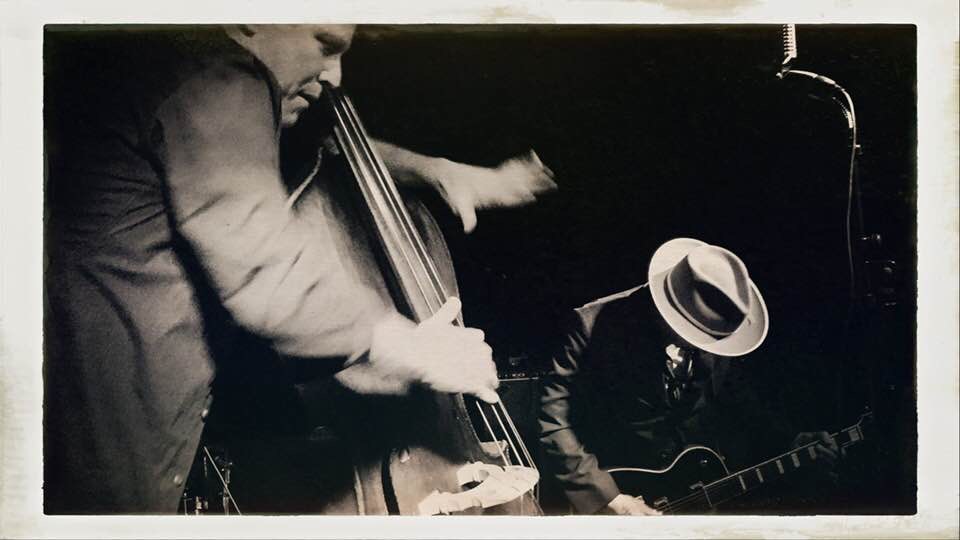

Stephen Ulrich is a guitar player, composer and leader of the band Big Lazy. Big Lazy is an instrumental trio from New York City. Their music dwells in the unmistakable landscape of gritty yet gracefully crafted American music. Simultaneously noir and pastoral, gothic and modern, Big Lazy conjures images of everything from big sky country to seedy back rooms. With sparse instrumentation—electric guitar, acoustic bass and drums—the trio creates richly evocative soundscapes with a distinctly narrative quality and an undeniable sense of place.

Stephen composed music for the HBO series Bored To Death and more recently, the film Art and Craft.

Kosmos | Stephen, what did you want to be when you were growing up?

Stephen Ulrich | Music was always a natural place that I thought I might end up. When I was a little kid, I remember looking at the Beatles’ album, Rubber Soul, and thinking they made it for us personally, that there was one album and it was for our family. I also loved the album cover itself. It could have been shot in our driveway, the pine trees, it just felt like a family portrait or something. That’s the connection I had to music. Playing music started relatively late, at 13. I thought about being an anonymous studio musician because those are the kind of people I studied with. Guys like Sal Salvador, legendary guitarist in New York, part of the RCA Orchestra. Not a rock star, but just earning a living playing music.

Kosmos | What influenced you to focus on instrumental music?

SU | I studied and played jazz, and that’s where I was headed. My mentor, Sal Salvador, taught in a dusty back room in the Ed Sullivan Theater and instrumental music became part of my DNA. I listened to Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery, classic stuff. I got into punk rock because I felt like jazz was somebody else’s music. Punk was the music of my generation. The incident that turned us into an instrumental band was a gig at CBGB’s Gallery in 1998. We had been working with a singer, Dino Ray, again reinventing by putting words to these dark, atmospheric tunes. The singer didn’t show but we went on anyway. Suddenly, it just felt natural. Within the first song, the crowd came right to us. It was a random act but it wasn’t an accident. Playing strictly instrumentals felt like a bit of a curse at first but it evolved into more of a blessing because now I license music and I write for films.

Kosmos | I’ve heard listeners describe your music as ‘the soundtrack to my life’. It connects at a visceral level with people who are experiencing turmoil in their lives. There is a raw honesty at the core of your work.

SU | Thank you. Yeah, the music is not consoling. It’s saying, ‘everything’s open and everything’s gray, not black and white’. The songs don’t have a happy ending. They don’t have a sad ending. You get to make up your own ending. I also get the description ‘good driving music’. It’s about the trip – telephone poles passing – not necessarily the arrival. There’s an element of human resistance and the power to act when you can actually write your own script.

Kosmos | There’s a yearning in the music, and also in your performance of it.

SU | There is an unresolved quality to the music which gives it a sense of danger but also sadness. Most of the tunes are in minor keys and to our Western ears the minor key lacks resolution. That quality of danger attracts film makers to use the music in dramatic situations. What I love about composing music is I’m using math – music theory – to affect people’s emotions.

We’ve gotten much better at performing this music over the years. It’s not exactly party music, although people do dance at our shows, but it does celebrate life and a has a how-goes-the-struggle? element.

Kosmos | Who are your fans?

SU | We have this new generation of punky kids that like the band and come to shows. They remind me of myself, approaching bands in 1980. When we were on NPR years ago, 1999, or thereabouts, on the show Weekend Edition which aired on Sunday mornings, I received thousands of letters. Thousands. I still have them, – they’re in boxes. The letters were from a whole variety of people. NASA people ordered the CD. Farmers, cops, film makers, skate punks, just the craziest mix of people. Maybe that’s NPR but I felt like the music struck this chord with people, and it just went across the whole spectrum.

Kosmos | That is archived at NPR. Here is a link

SU | Ooh thanks – I need this.

Kosmos | What is the role of the artist in these precarious times?

SU | People have told me this music enabled them to write their own script. I suppose that could sound like escapism, but it could also be about taking control. In that sense, there is an element of understated compassion to the music. The world’s just held together with duct tape right now. It’s hard to not be political personally, but in my music, it’s more of a crusade to stay free and not be beholden to these powers. The word noir is used a lot in our music. What is noir and what does that mean? It literally means darkness. It could be guys in trench coats but actually, I think the music has an underdog quality to it that appeals to people.

Kosmos | The licensing of the music and the work you do scoring television and film, is that a solo project of yours, or do you do that as a band?

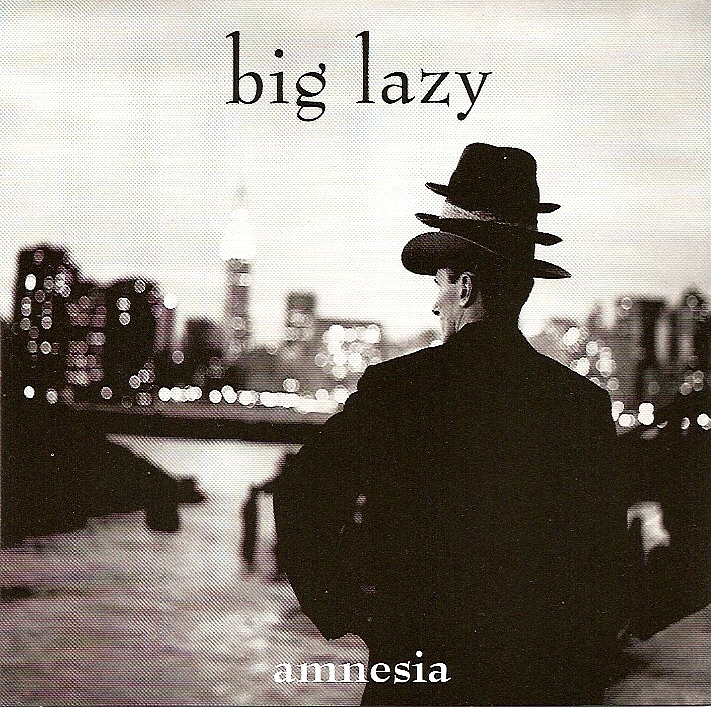

SU | Originally, it started out with the band licensing material. We put out a six song EP, Amnesia, and the entire album was licensed by NBC for use in the crime drama Homicide: Life on the Street. We also appeared performing onstage in an episode. Later, I wrote the music for the HBO series Bored to Death. The director, Alan Taylor, was a fan of the band and he used a bunch of songs in the pilot. HBO was like, “Let’s just hire this guy whose music we are already using.” It led to some odd moments where HBO would want me to copy ( industry term: ‘knock-off’) my own composition! The initial interest in licensing came from the band, but as far as scoring for film and televison, I’m a one-man operation. I do however bring the guys in to play on them.

Kosmos | Is scoring different than making songs for records?

SU | Totally different. When composing for an album I’m relatively free, but film composing is all about being in service of the film and director. At times you’re writing not so much what the actor is saying but what they’re thinking, or linking the scene to an earlier action. There’s a whole underlying structure that the viewer will sense but might not be fully conscious of. The best film music pulls you into the film emotionally; you don’t always keep track of what the score is doing. I once sent in a piece of music, and the director was having trouble with it. He commented, “This character is about to be in danger, but he’s not in danger right now. Okay, go. Send us something.” There are so many layers as opposed to writing music for an album where you’re just free. When I’m writing for a film, they’ll say, ‘We need a tango by 4:00 p.m.’ Done!

Kosmos | To what degree does licensing your music keep the lights on and the Big Lazy machine rolling?

SU | That’s where the money comes from, and that definitely keeps things moving, especially for me because I have a very large catalog of music that is used in a lot of different places.

Kosmos | As leader of Big Lazy, do you feel like the business guy, the conductor, the producer, the artist, the guitar slinger or all of the above?

Kosmos | As leader of Big Lazy, do you feel like the business guy, the conductor, the producer, the artist, the guitar slinger or all of the above?

SU | It’s more like cheerleader, cab driver and production designer. I’m constantly the one that says things like, “We’re going to drive 400 miles, but it’s going to be an amazing transformative night.” We’re a band of good friends. They love what we do, but I have to sell them on stuff. The music is obviously front and center but there’s also the presentation, the aesthetic, how everything’s defined, the fonts, just crazy detail.

Kosmos | It’s funny because on the cover of that early EP you referred to, is a picture of you wearing a bunch of hats.

SU | That’s funny, yeah. I never thought of that!

Kosmos | As part of a group, was it difficult to define and refine your low-fi film noir style? Was this something you had to sell them on or did the band members contribute to that?

SU | The original band was called Mild Thing, it was me, Paul Dugan on bass and singer Mark Rounds. This was 1990. We played despairing but humorous drinking songs. We added drummer Willie Martinez, Mark left us and we became Lazy Boy, playing moody instrumentals with too much reverb. We started dabbling in writing music for films and touring. The touring experience made us into more of a rock band, I was just feeling the need to make a racket instead of playing music that made people stare into their drink. The music became less theatrical and more visceral. In 1999 we were sued by the La-Z-Boy chair company for copyright infringement and with the addition of drummer Tamir Muskat, we became Big Lazy. We cultivated a kind of raw, bluesy sound full of fire and recorded 4 albums. After a hiatus starting in 2007 I reignited the band with Yuval Lyon (drums) and Andrew Hall (bass). The lo-fi film noir style was a slow and painful evolution!

Kosmos | Growing up in the punk rock era, we used to plaster the town with our DIY posters to create a visual and a band awareness and announce gigs. Has social media made things different for getting the word out now as opposed to how we did it back in the day?

SB | I’ll never forget that feeling of having a big stapler and an armful of flyers, and making Xeroxed artwork. I did that in early Big Lazy. Nowadays, with social media, everyone’s posting pictures of their sandwich. I use it sparingly. It’s really helpful if you have a gig in Nashville and you need to contact people. On the other hand, I feel like I’m taking part in the Evil Empire. It’s supposed to be about reaching people but there’s all these strange limits to it.

Kosmos | Do you feel like social media is helping you to build a community of fans?

SU | Yes, but in a way, email feels a little more respectful. “Here, we’re playing. If you want to come, you can come. You don’t have to respond.” A lot of what we do is completely done on our own. It’s just another tool.

Kosmos | To what degree has crowdfunding and crowdsourcing provided artistic freedom for your band?

SU | It’s not that different for us. We’ve never been beholden to a record company in terms of what we do artistically. What I did with both crowdfunding campaigns was, I individually emailed 2,000 people. Each time, it took me a month. That’s been the most connective thing I’ve done in terms of social media. I actually had hundreds of conversations with people through email, sometimes on the phone. In that way, it was a transformative thing, connecting to everybody directly.

Kosmos | Where do you go when you perform music. Can you describe your inner landscape at all?

Stephen Ulrich: When I write a tune, I almost always have this sense of place where the tune the piece lives. It could be my mother’s attic, or a parking lot that I was in once but somehow, the piece dwells in a specific location that haunts the song for the rest of it’s life! So I have a faint sense of that place when I’m performing. On a great night I just walk off stage and think to myself, “Where was I for the last hour?”

Kosmos | Nice. You have a new album coming out too, right?

SU | We do! It’s called Dear Trouble. It’s coming out in mid-October and we’re really excited. We brought in a bunch of New York luminary musicians as featured guests; Marc Ribot, Steven Bernstein, Peter Hess and woman named Marlysse Rose Simmons who’s a keyboardist. Checkered Past Records in Chicago is putting it out. It’s actually the first time we’ve used a label.

Kosmos | What about touring or gigs in support of that? Any immediate plans?

SU | Initially, we’re doing Northeast states; Philly, Boston, New York, New Haven, Connecticut. We just did a southern tour and we have plans to go to France in the spring.

Kosmos | Thank you Stephen. Just to leave you with a thought regarding the power that you wield, I found a quote by Ludwig van Beethoven. He said, the guitar is a miniature orchestra in itself. I thought, ‘Wow. That sounds like Stephen.’

SU | That’s great! Thank you!

VISIT | http://www.biglazymusic.com/