Awakening to Life

“I am life that wills to live in the midst of life that wills to live” – Albert Schweitzer

There was a debate that fascinated theologians in Christian Europe for a millennium or so, engaging them as recently as the nineteenth century. It revolved around this imponderable: If you’d lived a righteous life and your soul ended up in heaven for eternity, how could you remain beatific if you knew a loved one was suffering eternal torment in hell? One theory was that God wiped your mind clean of memories of any loved ones now enduring perpetual torture. Other prominent theologians, amazingly, suggested that those in heavenly bliss would simply rejoice when they heard the “dolorous shrieks and cries” of the damned, knowing that they got their just deserts.

The bizarreness of this question arises from a paradox deeply ingrained in the Western tradition: the supposed impermeable essence of the human soul. For millennia, people were told that their soul—their true identity—was a discrete eternal unit that was rewarded for a good life by permanent residence in heaven with God. Their bodily incarnation, with its complex desires and feelings for others, was a dangerous distraction tempting them from what really mattered. While the traditional Christian story of the soul might seem consigned mostly to history, it shares the same deep roots with our dominant neoliberal capitalist system, based upon the foundational idea of an individual as an autonomous agent utterly distinct from the rest of humanity.

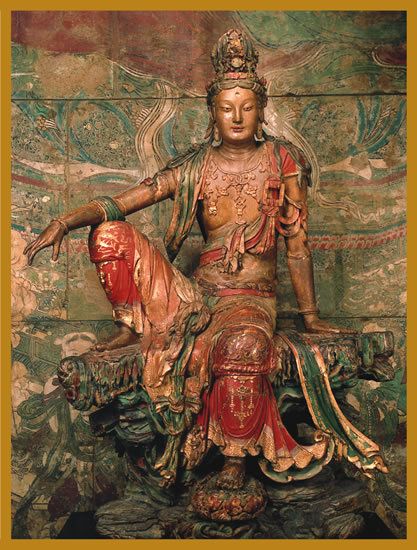

There is a telling contrast to the Christian story of the soul’s salvation in the Buddhist conception of the bodhisattva—someone who, having worked tirelessly to achieve enlightenment, has arrived at the threshold of nirvana with the opportunity to be released from persistent cycles of reincarnation. But rather than opting for liberation, the bodhisattva chooses to return to the world and work ceaselessly until all beings have awakened from needless suffering. This seems at first like an act of boundless altruism. However, a deeper analysis reveals something even more profound. The bodhisattva has achieved the realization that the boundaries separating the self from others are all mere constructions of a conditioned mind. In this “perfection of wisdom,” the bodhisattva recognizes her inherent interdependence with all sentient beings. She’s not sacrificing herself for the benefit of others—she has awakened to the realization that the very notion of a separate self is a falsehood.

Ultimately, our values arise from our identity. If someone defines themselves as an isolated individual, they will feel entitled to pursue their own happiness at the expense of others. Someone who identifies primarily with their nation will have no qualms about putting up barriers to prevent others from entering. If your identity is based on a fundamentalist religious creed, you may be ready to martyr yourself for the cause. And if you identify primarily with all life, you’re likely to devote your existence to work for the benefit of all sentient beings.

Our mainstream culture, forged in medieval Europe and rationalized by reductionist science from the seventeenth century onward, tells us to find our identity in separation, just like the Christian soul. Mainstream economists posit that humans are selfish, rational maximizers of individual welfare. Popularizers of outmoded scientific theories, such as Richard Dawkins, have successfully peddled the idea that we are machines driven by selfish genes, and any moral framework we construct must overpower our true nature “because we are born selfish.”

But that old worldview of separation has expired. It’s not just dangerous, leading us to the precipice of ecological devastation and climate breakdown—it’s plain wrong. Modern scientific findings from fields as diverse as systems theory, complexity science, cognitive anthropology, and evolutionary theory all point to the same fundamental insight that wisdom traditions such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Indigenous knowledge have been telling us for millennia: that our very existence arises from our interconnectedness—within ourselves, with each other, and with the living Earth.

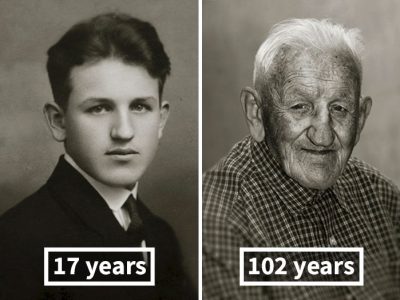

We learn from complexity science that the relationships between things are frequently more important than the things themselves. Think of a photograph of yourself when you were a child. You know it’s you, but virtually every cell within you now is different from what comprised that child—and even the cells that remain for life are constantly reconfiguring their internal contents, so you can be certain that not a single molecule in that little child is still part of you. And yet, you know you’re the same person. You have the memories to prove it. It’s the complex set of relationships between your different parts that retains the resiliency that links your personhood to that child. The same principle holds true for virtually all natural systems: candle flames, rivers, and ecosystems.

Far from being separate from the rest of nature, we are part of an endless meshwork of life going back over billions of years. Biologists explain that as a result of deep homology, fruit flies share more than half their genes with humans, and even bananas share 44 percent. The rich diversity of life on Earth arose, not from the selfishness of those genes, but because different organisms learned how to cooperate with each other in a stunningly complex network of mutually beneficial symbiosis. And as humans evolved into a unique species, cooperation was their defining characteristic. Alone among primates, we developed moral emotions—such as compassion, shame, and a visceral sense of fairness—that caused our identity to expand beyond individual selves and incorporate our entire group.

While this pervasive interconnectedness may seem surprising to modern mainstream thinking, it’s fundamental to the sense of identity that non-Western traditions foster. When members of the Native American Blackfoot tribe meet each other, they don’t ask “How are you?” Instead, they ask “How are the connections?” Similarly, in Central and Southern Africa, a guiding principle for life is ubuntu, which is frequently translated as “I am because you are, you are because I am.” In many Indigenous communities, the type of self-seeking behavior promoted by neoliberalism would be seen as a form of madness.

Traditional Chinese sages similarly based their moral compass on the foundation of the interrelatedness of all life, the realization of which they called ren. Philosopher Cheng Yi declared that a person who achieves the state of ren “regards heaven, earth, and all things as one body; there is nothing not himself.” This understanding was unforgettably expressed by Zhang Zai in one of the greatest expressions of human wisdom called the Western Inscription, which begins:

Heaven is my father and earth is my mother,

and I, a small child, find myself placed intimately between them.

What fills the universe I regard as my body;

what directs the universe I regard as my nature.

All people are my brothers and sisters; all things are my companions.

In the face of our civilization’s onslaught against life, an increasing number of modern Western visionaries are beginning to throw off the mantle of separation that has muddied the moral clarity of mainstream society—what Einstein called “a kind of optical delusion of consciousness . . . a kind of prison for us”—and rediscover the core truth of our shared identity.

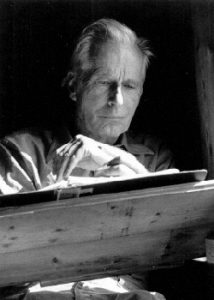

The founder of Deep Ecology, Arne Naess, called this expanded identity an ecological self. “We may be said to be in, and of, Nature,” he declared, “from the very beginning of our selves.” For the great humanitarian, Albert Schweitzer, who experienced his own identity as springing from life itself (as expressed in the epigraph) a system of values becomes self-evident: “I cannot but have reverence for all that is called life. I cannot avoid compassion for everything that is called life. That is the beginning and foundation of morality.”

Once we recognize that we are life, we are called by the overriding imperative to devote our own little eddy of sentience to the flourishing of all life, of which we are but one tiny part. With an expanded sense of identity, this becomes not so much a moral obligation as a natural instinct based on life’s own drive for flourishing. An ecological worldview leads naturally to acting out of love, which can simply be understood as the realization and embrace of connectedness. A deep recognition of interdependence can become a foundation for what Buddhist scholar David Loy calls “bodhisattva activism”—wherein each new situation presents an opportunity to re-orient from individual separateness toward a shared identity.

Part of becoming an ecological self is to find our participative role within a larger community of changemakers creating what George Monbiot calls the “new politics of belonging.” Just as trees in a healthy forest communicate with and fortify each other through their underground mycorrhizal network in a “wood-wide web,” each of us can be most effective in transformative change when we connect with the existing network of life-affirming groups already operating around us.

We have arrived at a stage in the human story on Earth where the decisions made over the next few decades will determine the future direction, not just of humanity, but of Earth itself. Ultimately, it will be a collective decision based on our shared sense of identity. While our civilization has been destroying much of life on Earth in the past few decades, we have also been developing a greater collective consciousness as a species than ever before. Can we wake up in time to appreciate our collective identity and participate in something greater than our fixed selves? As Thích Nhât Hanh has suggested, the next Buddha may not be in the form of an individual, but the awakening community.

A full recognition of interconnectedness brings with it myriad implications as we traverse its tapestry. Some pathways invite possibilities for the bliss of liberation from the confines of a bounded self. Other pathways open up grievous avenues of shared anguish as we become intimate with the suffering of others and the horrifying devastation of nonhuman life on Earth unfolding before us. Awakening to life in this century of turmoil is far from a painless experience. It takes courage, authenticity, and the humility to reach out to others when the enormity of the loss becomes too unbearable to hold in your own heart. But taken together, pursuing these pathways of awakening can imbue our lives with vibrant meaning as we participate in regenerating the Earth, in setting humanity and nonhuman nature on a course for the Symbiocene—an indefinitely prolonged period of mutual flourishing.

[Note: this article contains selected excerpts from Jeremy Lent’s upcoming book, The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find Our Place in the Universe.]

Dear Jeremy,

I savored your article and its insights.

Thank you for devoting your life to helping all of us find higher ground.

In peace,

Don Iannone

Great and illuminating article Jeremy. You are continuing to bring much needed light into and onto the world! Thank you!

From my heart to yours ~

Richard Henry Whitehurst

We’re 31ppm from 450ppm, which Michael Mann calls, “irreversible.”

Weak-kneed Democrats allow proto-fascists to rule from the minority.

The failure of S1 due to two Republican plants in the Democratic Party means vote suppression will elect Republicans, and Democrats will let that be.

Where is a future in that?