A Conversation with Alanis Obomsawin

Alanis Obomsawin is a member of the Abenaki Nation and one of Canada’s foremost activist documentary filmmakers. Obomsawin began her artistic life as a singer-songwriter in the 1960s, as indigenous artists from across North America were rallying in new assertions of cultural identity, consciousness, and political rights, calling for reckonings with oppressive colonial history. She was invited by Folkways to perform at Town Hall in New York City in the early 1960s, and spent most of that decade primarily identifying as a musician and social activist, channeling traditional First Nations songs hand-in-hand with modern composition and arrangements.

In the mid-1980s, Canada’s national broadcaster, CBC Radio (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) invited Obomsawin to record an album; unsatisfied with these recordings, she reclaimed the master tapes, remixed the material, re-recorded the title track from scratch, and issued the ensuing Bush Lady album on her own private press in 1988 complete with her own artwork and liner notes. The album has grown to become an increasingly legendary rarity ever since.

Bush Lady is a unique and magical record by any definition. It’s an invaluable example of contemporary First Nations music that blends traditional folkways with avant-garde composition. Bush Lady was re-released by Constellation Records in June of 2018.

Dream Magic

This National Film Board of Canada portrait of filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin was shown at a gala ceremony in 2008, where Obomsawin received the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement. Her work has captured important events in Canadian history, including the armed standoff between the Canadian Army and Mohawk warriors in 1993. At age 86, she continues to make films that cross a spectrum of social issues.

The Interview

Kari Auerbach | You are known mainly as a filmmaker. I have seen about five out of your more than 50 films, and they’re fabulous films. They’re really wonderful.

Alanis Obomsawin | I’m working on my 52nd film now.

Kari | That is amazing! You have also been making music since the ’60s, and that’s what I want to focus on. Bush Lady, originally released in 1988, is now being re-released 30 years later. This sounds, to me, like a fascinating story. How did this re-release come about?

Alanis | Well, it came about because an employee here at the National Film Board, Frédéric Savard, saw the cover of my old Bush Lady record and was curious. He came to my office and asked me if he could buy one. I said, “Buy one? I’ll give you one.” Then he came back and he said that he just loved it, and asked if I still had some. He wanted to sell them and he sold everything I had left! He sold the first one to a producer for this folk festival called Le Guess Who? in the Netherlands.

Kari | Which is a huge festival!

Alanis | Yes, so then I was invited to go there and do a concert, and I was very nervous, because I hadn’t done concerts for years. I still sing, but for ceremonies. Maybe a chant, or when people die, things like that, but I hadn’t done any concerts for 30 years, Finally I said yes, and I did it, and it was very, very well received by the audience. So, then this company, Constellation, wanted to re-release it, so it happened! It just came out just a few months ago, and they did a really fantastic job.

The sound is beautiful, with a very beautiful presentation. It’s strange, it feels as if it’s a new record that just came out, and on the other hand, it’s a little bit sad, because when I wrote the Bush Lady song, it was about a situation here in Canada for a lot of women. Many years have passed, yet it’s still very relevant.

In general, Canadians are very respectful and are really listening to the history and what's happened to our people. People are starting to be interested and understand better the situation of our people in this country. It's bringing out a lot of feelings for many different nations.

Kari | The arrangements on Bush Lady are very contemporary, and that makes it feel like this record is landing at a very appropriate time. Were there any changes to the music from the original release?

Alanis | No. From my original release in ’88, it’s the same music for Bush Lady. The rest of the music for the other songs came from the CBC, who had taped me and made a record earlier, I forget what year. Maybe ’85, I’m not sure.

Kari | Of the people who bought it the first time around, was it well received?

Alanis | It was well received and people loved it, and it was very much telling a story of the time, but I couldn’t handle selling it and collecting the money for it myself.

Kari | There’s been a sustained interest for a long time in this record, and the messages in Bush Lady have real global resonance. But there is a specific sector of people you wanted to give a voice to in your music when it all started, and in your films, too, so your art seems like a tool to tell stories that raise awareness and invoke change. Was music always that way for you?

Alanis | I try to educate, that was my main thing. I really was annoyed by the way history was taught in the classroom, very much against our people, and I wanted to change that. That was my revolt against the educational system of the time.

Kari | In some parts of the record, you’re singing in English, and you also sing in French. The other language you sing in, is that the Abenaki language? What is that called?

Alanis | Some of the songs are in Abenaki in there. Odana is in Abenaki.

Kari | It’s beautiful! The first song on Bush Lady is so gorgeous and wistful… Odana. Does that mean ‘of Odenak’?

Alanis: Yes. Odana means village, or town, and Odanak with a “k” is at the village, or at the town.

Kari | Are you singing about where you grew up in that song?

Alanis | Yes. That’s where I grew up.

Kari | The song Bush Lady is a journey of a woman, and it’s so solitary, unfair, and filled with suffering. When you’re singing it, how do you channel and restrain your emotions so well to keep the rhythm and stay true to that story?

Alanis | Well, it’s hard, but I do it.

Kari | You do it so well. And when we revisit the woman in the song Bush Lady, Part 2, the narrator identifies themselves in the lyrics by saying, “this is your …” and then there’s a word I don’t understand …“talking to you.” I cannot make out that word. Can you fill me in with the word and tell me what it means?

Alanis | Nookom, or nookomis, means grandmother in Algonquin languages. It’s her grandmother.

Kari | The maternal side, coming to finally care for her and give her dignity and respect.

Alanis | Yes. As she died.

Kari | She’s dying, and it’s very sad. I don’t have a favorite on the record, but that one is very, very moving, and very, very soothing. Have you seen changes for the better in the lives of the women and children who you document in Canada?

Alanis | I’ve seen a lot of good changes in recent years … with the education system. There’s a lot of good things happening in a lot of the communities. People are made aware more than ever about the missing women that have been killed, street women. It’s still happening. For our people, for a long time, they believed what they were told about who they were. That’s also a very sad part of our lives.

Kari | Yes, it is very sad but I think it’s your compassion, your poetry, and your natural want of better education that helped to shine a light. I feel very hopeful, because I believe that with awareness comes the possibility of change. I was curious to see if it’s already happening.

Alanis | I think that people are more respectful and more caring, and wanting to know more. I find that people are really listening now, where 10 years ago, it was, “Oh, these Indians, they’re always complaining.” That’s the only kind of stuff we heard. But it’s very different now.

Kari | I think it’s very important that you’re able to pass that on in song and poetry because history is often made by those who write it. In the ’60s, you also toured schools to sing to the children.

Alanis | Oh, yes! Before making films, I toured hundreds and hundreds of schools, mainly in Canada, some in the States, and some in Europe. I think I really influenced a lot of change there.

Kari | Yes, you were planting the seeds of a lot of the changes we’re seeing today. Do you have plans to do any more of that? I know your schedule is very busy.

Alanis | Educate the children, but also educate the rest of the country.

Kari | Do you think you’ll have any opportunities to sing in schools anymore?

Alanis | Oh, I have all my life.

Kari | So you’ve kept that going.

Alanis | Yes, yes.

I feel very, very lucky to have lived this long and to have seen changes, and to have seen our young people standing up for themselves and talking like old people, talking about spiritual things in life. Some of them have had drug problems or alcohol problems, and often when they get up from that, they're the strongest of all.

The way they speak and the way they take part in ceremonies…encouraging young people against suicide, because we’ve had a lot of suicides. The responsibility that they take, with so much love in their heart, and so much belief that things will be better, and they ARE better! More and more, the more young people realize they are the ones that are responsible for a lot of change too.

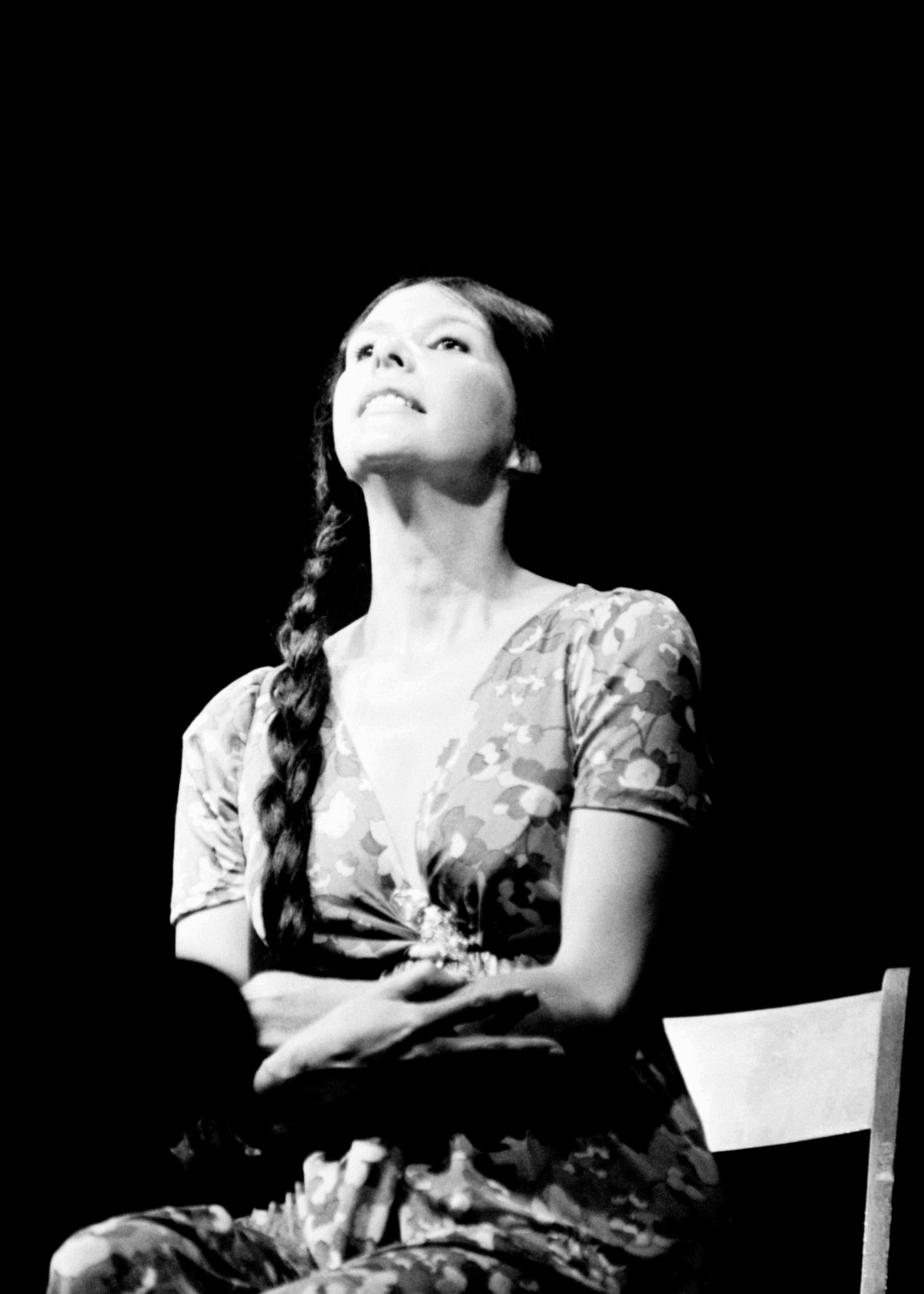

This mural is an initiative and production of MU, a charitable nonprofit mural arts organization that wanted to honor Alanis as “An engaged artist who has used her art, her voice, at the service of social change.” Alanis (wearing red to honor and raise awareness of missing and abused indigenous women) is standing with (l to r) Rafael Sottolicio, who directed the mural’s creation; Arnaud Gregoire, assistant muralist; and Meky Ottowa, the artist who designed it. Charged with symbolism, the piece is a dreamlike portrait of Alanis Obomsawin based on a photo of her singing at the Mariposa Folk Festival in Toronto (1970). The mural was made possible thanks to Ville de Montreal’s Mural Arts Program.

Alanis’s comments on the mural:

“I was so surprised when they told me I was receiving this honor. It’s very important to me that there are children beside me on the mural. What joy! These are children from Moose Factory, on James Bay in Northern Ontario, who went to a residential school in 1968, and I would play with them at recess. And it is such a gift to know a First Nations artist was chosen for this project. Not only has Meky Ottawa given us her work, but it has given her a chance to learn and share with a group of artists who are experts in making murals. Personally, I’m thinking of my parents; I don’t know what they would say. My father would look in silence and be moved.”