The Practice of Lucid Dreaming

When one goes to sleep, he takes along the material of this all-containing world, himself tears it apart, himself builds it up, and dreams by his own brightness, by his own light. Then this person becomes self-illuminated. There are no chariots, spans, roads. But he projects from himself chariots, spans, roads. There are no blisses there, no pleasures, no delights. But he projects from himself blisses, pleasures, delights. . . . For he is a creator.

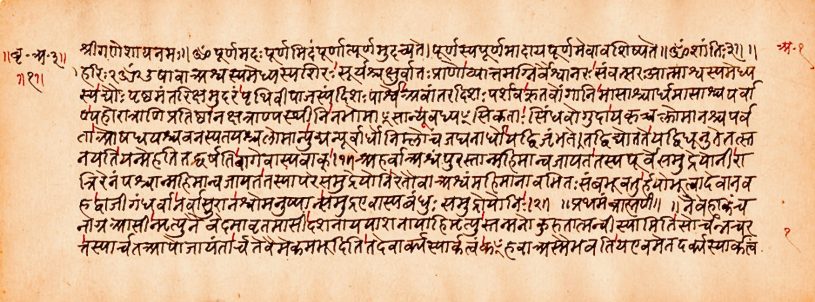

– Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 6th Century BCE.

The earliest religious texts among the people of the Indus River Valley, known as the Vedas, included a variety of practical measures to please the gods, including prayers, ethical precepts, and instructions for rituals and sacrifices. At some point after the Vedas, another kind of religious text emerged, the Upanishads, written by unknown figures over many centuries. Turning the focus of religious practice inward, the Upanishads presents a mystical philosophy of the self.

The spiritual insights in these texts can be profound, and, in the realm of dream research, highly relevant to our present-day concerns. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad presents a model of dream formation that seems to rely on nothing other than the creative power of the dreamer’s own mind. No gods or demons are involved, no journeys of the soul, no mingling with spirit beings. All that appears in dreaming, according to this text, is projected from the dreamer, drawing on the energy of “his own brightness, his own light.” This might sound like a surprisingly modern theory, close to what we dream researchers today call the neurocognitive approach. And yet the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad places dreams within a bigger framework of the spiritual evolution of consciousness. The text describes four basic states of being: waking, dreaming, dreamless sleep, and turiya, which is a transcendent state of divine immersion and infinite consciousness. In this setting, the exploration of dreaming becomes a valuable source of spiritual growth.

This realization—that the inner light of your unconscious generates the worlds of your dreams—can become a stepping stone toward the higher realization that the divine light creates the world of your waking reality.

Just as God creates the universe, you create your dreams. To see more of that creative power in yourself is to see more of it in the world too.

In the contemporary study of dreams, the biggest of big fish for many researchers is consciousness—specifically the kind of consciousness that appears in lucid dreams. Maybe you have experienced dreams yourself, in which you were aware of being within a dream. Perhaps you have never had a dream like that, and you are curious why some people get so excited about the idea. For as long as I have been in the field, researchers have been arguing about the nature and significance of lucid dreaming.

We in the modern West did not “discover” lucid dreaming. As indicated by the opening quote from the Upanishads, people throughout history have been familiar with variations in self-awareness within dreaming. In later Buddhist traditions in India, China, and elsewhere, efforts were made to extend classic practices of meditation into sleep, with the resulting insight into the self-created nature of reality. Here is a passage from The Life of Milarepa, a sacred autobiography by a famous Tibetan Buddhist sage from the eleventh century CE:

During the day I had the sensation of being able to change my body at will and of levitating through space and performing miracles. At night in my dreams I could freely and without obstacles explore the entire universe from one end to the other. And, transforming myself into hundreds of different material and spiritual bodies, I visited all the Buddha realms and listened to the teachings there. Also, I could preach the Dharma to a multitude of beings. My body could be both in flames and spouting water. Having thus obtained inconceivably miraculous powers, I meditated joyfully and with heightened spirit.

Rubin Museum of Art | Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin

C2006.66.460 (HAR 921)

This sounds like a peak lucid dreaming experience. And yet, in the context of Milarepa’s life and spiritual development, it only marked a momentary stage in his further growth. Two points are crucial here: first, Milarepa’s incredible powers did not appear instantly but only after years of patient training and meditation practice. There is no fast and easy method for having these kinds of dreams. And second, Milarepa did not become attached to these powers, as if becoming a magician was the goal; rather, he let them fall by the wayside as he moved forward in his spiritual journey.

A similar insight comes in another classic work of Asian spirituality, The Inner Chapters by the Daoist sage Zhuang Zi in the third century CE. You may already be familiar with this text, in which Zhuang Zi shares an extremely vivid dream of being a butterfly, flying freely in the air. Then he suddenly wakes up and wonders if he’s a man who dreamed of being a butterfly or a butterfly who is now dreaming of being a man.

For Zhuang Zi and the Daoist tradition, his dream offers a memorably poetic expression of the higher truth of the transformation of all things. Within this lineage of spiritual wisdom and practice, gaining magical powers matters far less than learning to recognize the endless flow of consciousness as it shifts from one state to another.

Becoming a Lucid Dreamer

In developing dream recall, as with any other skill, progress is sometimes slow. Don’t be discouraged if you don’t succeed at first. Virtually everyone improves through practice. As soon as you recall your dreams at least once per night, you’re ready to try lucid dreaming.

Keeping a dream journal

Get a notebook or diary for writing down your dreams. The notebook should be attractive to you and exclusively dedicated for the purpose of recording dreams. Place it by your bedside to remind yourself of your intention to write down dreams. Record your dreams immediately after you awaken from them. You can either write out the entire dream upon awakening from it or take down brief notes to expand later.

Your dream journal is a tool, and you are the only person who is going to read it. Describe the way images and characters look and sound and smell, and don’t forget to describe the way you felt in the dream—emotional reactions are important clues in the dream world. Record anything unusual, the kinds of things that would never occur in waking life.

Dreamsigns: Doors to Lucidity

A strange little detail in your dream may help you to realize you are dreaming. I have named such characteristically dreamlike features “dreamsigns.” Almost every dream has dreamsigns, and it is likely that we all have our own personal ones.

Once you know how to look for them, dreamsigns can be like neon lights, flashing a message in the darkness: “This is a dream! This is a dream!” You can use your journal as a rich source of information on how your own dreams signal their dreamlike nature. By training yourself to recognize dreamsigns, you will enhance your ability to use this natural method of becoming lucid.

Autosuggestion Technique

Relax completely

While lying in bed, gently close your eyes and relax your head, neck, back, arms, and legs. Completely let go of all muscular and mental tension, and breathe slowly and restfully. Enjoy the feeling of relaxation and let go of your thoughts, worries, concerns, and plans. If you have just awakened from sleep, you are probably already sufficiently relaxed.

Tell yourself that you will have a lucid dream

While remaining deeply relaxed, suggest to yourself that you are going to have a lucid dream, either later the same night or on some other night in the near future. Avoid putting intentional effort into your suggestion. Instead, attempt to put yourself in the frame of mind of genuinely expecting that you will have a lucid dream tonight or sometime soon. Let yourself think expectantly about the lucid dream you are about to have. Look forward to it, but be willing to let it happen all in good time.

Excerpt from: Exploring The World Of Lucid Dreaming

A Step By Step Guide By Stephan Laberge

Internet Archive

Turiya is not that which is conscious of the inner (subjective) world,

nor that which is conscious of the outer (objective) world,

nor that which is conscious of both, nor that which is a mass of consciousness.

It is not simple consciousness nor is It unconsciousness.

It is unperceived, unrelated, incomprehensible, uninferable, unthinkable, and indescribable.

– Mandukya Upanishad

All composed things are like a dream, a phantom, a drop of dew, a flash of lightning.

That is how to meditate on them, That is how to observe them.

– The Diamond Sutra

Just as, O king, a dream is unreal, so is the universe. Who is it who constructs the universe? This is also unreal.

– The Questions of King Milinda (Milindapañha)

It is clear that all three major religious traditions of Asia—Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism—have been familiar for thousands of years with experiences of self-awareness in dreaming. More than that, all three of these traditions have developed practices aimed at cultivating these kinds of dream experiences and channeling their energies toward spiritual growth and enlightenment.

Much less attention to the conscious dimensions of dreaming appears in Western history. Although the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle mentions in passing the occurrence of self-awareness in dreaming, he gives no special attention to it. The rise of the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam put more emphasis on the content of dreams as messages of divine reassurance and prophetic warning. But they bracketed out the questions Zhuang Zi and other Asian mystics were asking about the form of dreaming as a state of consciousness.

Eventually, in modern Western society, it no longer became possible, as a matter of linguistic usage and common sense, even to speak about self-awareness in dreaming. Talking about being aware in a dream was like talking about the coolness of fire or the softness of a rock: you were making no sense. People could talk about lucid dreams in the context of occult and esoteric writings, but these reports were often meandering and impressionistic, making it easy for mainstream scientists to dismiss them out of hand.

Making broad generalizations about something as complex and multifaceted as human religiosity is difficult. Yet the historical evidence suggests a real difference of attitude toward lucid dreaming between the Asian religious traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Daoism, on the one hand, and the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, on the other.

The former group, by and large, acknowledges the varieties of consciousness in dreams and sees this as a spiritual opportunity. The latter group, by and large, ignores consciousness in dreaming and regards it as spiritually irrelevant. Most Indigenous cultures, especially those with shamanic practices, would seem to side with the Asian religious traditions on this issue.

Neither perspective is ‘right or wrong’. If nothing else, this brief history suggests that the current excitement about lucid dreaming in the modern West might represent a kind of cultural rebound effect. Perhaps many of us are experiencing a new surge of interest in lucid dreaming because our culture has paid such minimal attention to this aspect of our dreaming selves for centuries.

Excerpted with kind permission.

The Spirituality of Dreaming: Unlocking the Wisdom of Our Sleeping Selves by Kelly Bulkeley

Available now: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, Broadleaf Books