A Different Kind of Fast

featured image | Becca Clark, Pixabay

Fasting can help us to remember our true hunger. At heart, the act of fasting is about growing in relationship to the sacred presence. Experiencing hunger gets us in touch with the desire for something we do not have. It is the longing for it and our deep need. But we can get overwhelmed by our hungers for things, especially in a culture that worships consumerism and in which the divide between rich and poor grows ever wider. Stepping back from this helps us to see what we are really yearning for in our lives.

I think of my habit of clearing off my desk and filing away old papers when I am starting on a new project. If I prolong this task it may slip into procrastination, but the impulse and desire is to remove some of the external clutter, which creates a sense of inner spaciousness as well.

The outer clutter and inner clutter are often reflections of each other. I have fewer distractions from the project I want to be working on, and it makes it a more satisfying process for me. I find this too when I rearrange the furniture in a room: I suddenly get a new perspective. Fasting can create breathing space for a new perspective on our lives. We have been so used to looking at things a certain way, we discover with small shifts there is so much more beneath the surface awaiting our attention.

Fasting from foods is only one kind of fast. There are many other kinds too. We can fast from acquiring more “things,” and excessive consumption, as the physical and material realm, as the materiality of food, and how we understand it, limit it, or explore it differently, becomes a portal to the spiritual. We may find that cleaning the house and preparing a beautiful meal lend themselves to celebratory occasions – different kinds of fasting – and help to lift us from the mundane moments to open us to a deeper connection with God.

In a world where the sacred is infused into the material world, what we release on the physical realm can also impact our interior life. Fasting is preparation, which means clearing out a space for something new to enter.

Fasting isn’t only connected to a physical level. We can also fast from thoughts and patterns in our lives that are life-denying. Fasting creates space in our lives for other- life-giving – thoughts to emerge. Rather than feeling jostled about by so many conflicting internal thoughts or tasks, when we fast, we make room internally for something else, and we are able to breathe more deeply.

In the Hebrew Scriptures, the prophet Isaiah speaks about fasting as profoundly connected to transformation, both personal and cultural. When we release our life-denying habits and thoughts, we discover a new freedom to live differently. This is an internal freedom not dictated by circumstances. Ultimately this internal freedom leads us to desire for liberation for all beings and Isaiah makes this connection to justice:

Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin? (Isaiah 58:6-7 (NRSV)

As this wisdom text reveals, fasting helps reveal our true hunger and the hunger of others. And in the process of discovering this, we begin to see what is life-giving for us as intimately intertwined with the well-being of the entire Earth community. We don’t fast merely for personal transformation, although this is a step along the way. We fast to widen our vision on ourselves and ultimately to connect to our longings to bring conditions of freedom for all.

Not only does fasting connect us to our true hunger, it has a way of also attuning us to the greater mystery in which we, as the book of Acts says, “live and move and have our being” (17:28). Thomas Ryan deepens our understanding of how fasting functions, writing:

Fasting as a religious act increases our sensitivity to that mystery always and everywhere present to us. It is a passageway into the world of spirit to explore its territory and bring back a wisdom necessary for living a fulfilled life. It is an invitation to awareness, a call to compassion for the needy, a cry of distress and a song of joy. It is a discipline of self-restraint, a ritual of purification, and a sanctuary for offerings of atonement.

I love this litany of the fruits of fasting. When we fast, we make space to see the sacred thresholds shimmering everywhere we go. It brings us more fully present to the world and to those in need. It helps us to heal our wounds and creates room for joy. Atonement is a process of removing obstacles between ourselves and God. Fasting is an intentional removing those things that lead us further away.

I am sometimes asked how we know if we have an authentic encounter with the divine and my answer is always love. When our hearts are expanded and we start to see our fellow living beings as worthy of our care, then we know the sacred has been moving in our hearts.

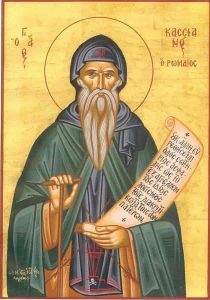

One of the early teachings of the Christian church find helpful to understand fasting is from John Cassian. Cassian, an early theologian, writes about what he calls the three renunciations. Renunciations are an intentional giving up of certain patterns or ways of being in the world and one form fasting can take. For Cassian, the first renunciation is of our former way of life and shifting our focus to our heart’s deep desire. He assumes his listeners have perhaps become too invested in pleasing others, in achievements, or other externally focused motivations for how we live. By beginning to intentionally turn our attention inward, we listen for the way holy direction. the sacred pulses in our own hearts call us to live from this

One of the early teachings of the Christian church find helpful to understand fasting is from John Cassian. Cassian, an early theologian, writes about what he calls the three renunciations. Renunciations are an intentional giving up of certain patterns or ways of being in the world and one form fasting can take. For Cassian, the first renunciation is of our former way of life and shifting our focus to our heart’s deep desire. He assumes his listeners have perhaps become too invested in pleasing others, in achievements, or other externally focused motivations for how we live. By beginning to intentionally turn our attention inward, we listen for the way holy direction. the sacred pulses in our own hearts call us to live from this

The second renunciation, Cassian says, is giving up our mindless thoughts. Our minds are full of chatter all the time: judgments about ourselves and others, fears and anxieties over the future, overwhelm at world issues, the stress of illness, stories we tell about our lives, regrets over the past, imagined conversations with others, and more. It can be exhausting to follow all these trails of anxiousness. Intentional thought and meditative practice have always been about calming the mind so that the spirit can listen to another, deeper, truer voice. In the beginning we may need to start by focusing our thoughts on an object of attention, as in centering prayer where we choose a sacred word to bring our awareness back to the divine. As we continue this practice, however, we eventually may find ourselves not needing to focus thoughts anymore, but simply listening to the heart’s wisdom. We begin by mak- ing the conscious choice to listen by quieting and clearing out the babble and prattle of our minds so that the heart’s shimmering can become the focus.

The third renunciation I find the most powerful. We are called to renounce even our images of God so that we can meet God in the fullness of that divine reality beyond the boxes and limitations we create. So many of us have inherited harmful images of God taught by others that are not fruitful to our flourishing. Images of a judgmental God, a vending-machine God, a capricious God, a prosperity God, a God made in the image of whiteness. We project our human experiences onto the divine. This is a natural impulse, but our soul’s deepening depends upon our freeing ourselves from these limiting images so we might have an encounter with the face of the sacred in all of its expansiveness and possibility. We might feel called to fast from these life-denying images to open our hearts to something wider.

We do not have to retreat to the desert or join a monastery to find this path of deepened intimacy with God. We each have the opportunity to choose this inner work of discerning what we hold onto and what we release at every season of our lives. We each have the choice to make. Sometimes this kind of radical simplicity accompanies a move, for example, when downsizing from a family home to an apartment. Sometimes we are forced by circumstance to change our outer life, perhaps due to illness or taking care of a sick parent. This inner transformation we are all called to seek.

One of the beautiful aspects of the Christian liturgical cycle is that the call to reflection and intensified spiritual practice returns again and again each year and meets us wherever we are. The purpose of these acts of letting go is always in service of love. When we fast out of a misplaced sense of competition or a diet mentality, we lose this focus and it becomes something that distorts reality rather than clarifies it.

When we fast, we stand humbly in the presence of the sacred and admit our humanity. We allow ourselves to be fully vulnerable and ask for the support in transformation we all need. We do not fast by our own sheer will, but by seeking the ground of being that supports and nourishes us as we grow.

One of my favorite scripture passages is from the prophet Isaiah:

Now I am revealing new things to you, things hidden and unknown to you, created just now, this very moment. Of these things you have heard nothing until now. So that you cannot say, Oh yes, I knew this. (Isaiah 48:6-7)

Ultimately, we fast so as to clear space within our minds and hearts and souls to await what holy newness is being revealed to us and to recognize it at work, as Isaiah says, “Created just now, this very moment.” God is at work moment by moment, bringing new life to birth in places we did not expect. I love of that passage, the second part which reminds us that the cynical part of our minds, which wants to say that we’ve seen it all, that nothing can surprise us any longer, is too narrow to witness what is unfolding right now.

My hope is that this will be an invitation for you to expand your concept of what fasting might mean for you and the gifts it has to offer, a way to witness those things hidden and unknown. Not just to stop eating chocolate, but to fast from things like “ego-grasping” or control, so that, in yielding yourself, a greater wisdom than your own is revealed.

My hope is that this will be an invitation for you to expand your concept of what fasting might mean for you and the gifts it has to offer, a way to witness those things hidden and unknown. Not just to stop eating chocolate, but to fast from things like “ego-grasping” or control, so that, in yielding yourself, a greater wisdom than your own is revealed.

We become aware of and fast from destructive patterns in our lives and direct our attention and energy toward what is life-giving, toward our true hunger and the feast. We let go of something depleting so we have more space to embrace what is life-giving and to nourish our true hunger.

And then perhaps from these Lenten fasts, we will arrive at Easter and realize those things from which we have fasted we no longer need to take back on again. We will experience a different kind of rising.

Reprinted with permission from A Different Kind of Fast: Feeding Our True Hungers in Lent by Christine Valters Paintner copyright © 2024 Broadleaf Books.