The Tree Saviors of Chipko Andolan | A Woman-led Movement in India

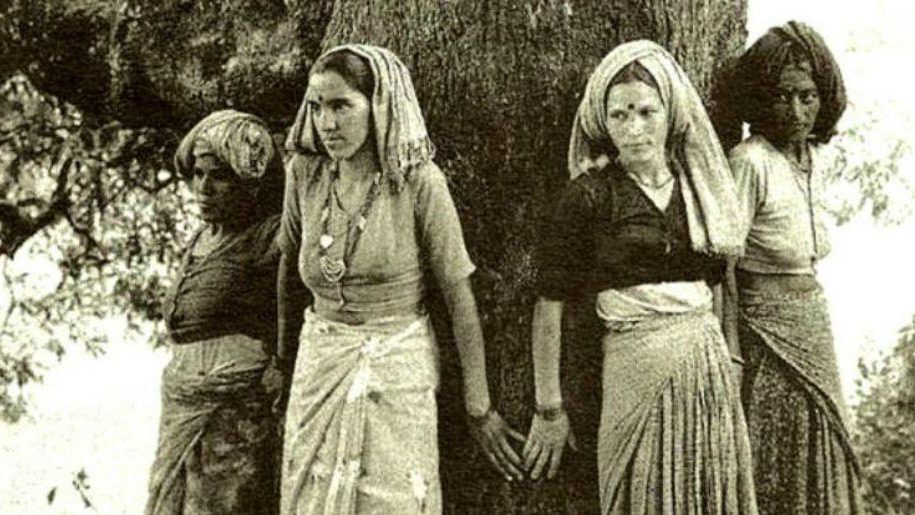

While pursuing my PhD, I became involved as a volunteer in the Chipko movement, a nonviolent, peaceful response to the large-scale deforestation that was taking place in the Garhwal Himalaya by peasant women from the region, who came out in defence of the forests. Chipko means “to hug,” “to embrace.” Women declared that they would hug the trees to protect them—loggers would have to kill them before they felled the trees.

Logging had led to landslides and floods, and to the scarcity of water, fodder, and fuel. Since women service these basic needs, scarcity meant longer walks for collecting water and firewood, and a heavier burden to bear. Women knew that the real value of forests was not the timber from a dead tree, but springs and streams, food for their cattle, and fuel for their hearths. The folk songs of that period said,

These beautiful oaks and rhododendrons,

They give us cool water.

Don’t cut these trees,

We have to keep them alive.

It took the 1978 Uttarkashi disaster, which created floods all the way to Calcutta in Bengal, for the Indian government to recognise that the women were right because the expenditure on flood relief far exceeded the revenues they were generating through timber. In 1981, in response to the Chipko movement, logging was banned above 1,000 kilometers in the Garhwal Himalaya. Today, government policy recognises that in the fragile Himalayas conservation maximises the ecological services of the forest.

The women activists of Chipko became my professors in biodiversity and ecology. I have always said that I received one PhD on the Foundations of Quantum Theory from the University of Western Ontario in Canada, and a second one on ecology from the forests of the Himalaya and women of the Chipko movement. Both taught me about interconnectedness and non-separability. The women of Chipko taught me about the relationship between forests, soil, and water and women’s sustenance economies; quantum theory taught me the four principles that have guided my thinking and my life’s work—everything is interconnected, everything is potential, everything is indeterminate, there is no excluded middle; we are interbeings.

The quantum world is not made up of fixed particles, but of potential. A quanta can be a wave or a particle. It is indeterminate, therefore, uncertain. It is non-separable, non-local. Therefore, action at a distance becomes possible. And contrary to the mechanistic ideal of nature-human separation, the observer “creates” the observed. An interactive, interrelated world becomes possible.

While the mechanical view forms the basis of mastery and conquest over nature, and hence is at the root of the ecological crisis, quantum and ecological paradigms have the same underlying understanding of an interconnected universe.

From the trees we learn unconditional love and unconditional giving. From the dry leaves that fall, we learn about the cycle of life and the law of return as leaves become humus and soil, protecting the earth, recycling nutrition and water, and recharging springs, wells, and streams. Forests also teach us “enoughness” as the principle of equity, enjoying the gifts of nature without exploitation and accumulation.

The diversity, harmony, and self-sustaining nature of the forest formed the organisational principles guiding Indian civilisation; the “aranya samskriti” (roughly translatable as “the culture of the forest”) was not a condition of primitiveness, but one of conscious choice.

My own biological life and ecological journey started in the forests of the Himalaya. My father was a forest conservator, and my mother chose to be a farmer after becoming a refugee following the tragic partition of India in 1947. It is through the Himalayan forests and ecosystems that most of my learning of ecology took place.

The lessons I learnt about diversity in the Himalayan forests have been transferred to the protection of biodiversity on our farms. Navdanya, the movement for biodiversity conservation and organic farming that I started in 1987, has saved seeds through creating community seed banks, and has helped farmers make the transition from fossil fuel and chemical-based monocultures to biodiverse ecological systems nourished by the sun and the soil. Biodiversity has been my teacher of abundance and freedom, of cooperation and mutual giving.

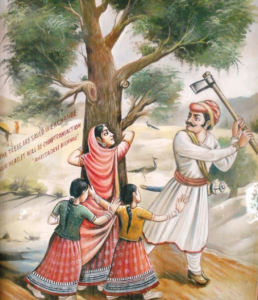

But the Chipko movement of the 1970s was not India’s first. In an earlier Chipko, in 1730, in Rajasthan, 363 people sacrificed their lives to protect their sacred khejri tree (prosopis cineraria). The khejri stands as a sentinel in the desert landscape of Rajasthan, as its poem. It is vital to sustainability in a desert ecosystem, as a source of fuel, firewood, and organic fertiliser. Its fruit, saangri, is rich in protein and is used to prepare pickles and vegetables. The shade of the khejri conserves moisture in the soil, and offers protection from the scorching sun to humans and animals.

The khejri was declared a sacred tree by Jambhoji, a saint, who founded the Bishnoi faith. Bishnoi means 29, and the faith is based on 29 rules of compassion and conservation. During a discourse to one of his disciples, Jambhoji said,

Do not fell a green tree,

This is a charter for everyone.

Be always ready to save (trees),

This is the duty of everyone.

For over two centuries, people living in accordance with these tenets created flourishing groves of trees and protected wildlife in the Rajasthan desert. One such Bishnoi village was Khejarli, situated 20 kilometres south of Jodhpur. When the king’s palace was being built, a court official, Girdhar Das, was made responsible for procuring firewood to burn the limestone required to make lime. A group arrived at the house of Amrita Devi, at home with her three young daughters, Asu Bai, Ratni Bai, and Bhagni Bai. Amrita Devi had a giant khejri growing at her doorstep. When the king’s men started to cut the tree, she tried to stop them, saying the cutting of green trees was against her religion. She said she would rather sacrifice her life than sacrifice the tree. She offered her head, and the axeman cut off her head. Her daughters followed; they, too, were beheaded. The news spread like wildfire, and Bishnois from 84 villages gathered in Khejarli to join the stream of volunteers to protect the trees; 363 people sacrificed their lives, and the sacred khejri trees were saved.

For over two centuries, people living in accordance with these tenets created flourishing groves of trees and protected wildlife in the Rajasthan desert. One such Bishnoi village was Khejarli, situated 20 kilometres south of Jodhpur. When the king’s palace was being built, a court official, Girdhar Das, was made responsible for procuring firewood to burn the limestone required to make lime. A group arrived at the house of Amrita Devi, at home with her three young daughters, Asu Bai, Ratni Bai, and Bhagni Bai. Amrita Devi had a giant khejri growing at her doorstep. When the king’s men started to cut the tree, she tried to stop them, saying the cutting of green trees was against her religion. She said she would rather sacrifice her life than sacrifice the tree. She offered her head, and the axeman cut off her head. Her daughters followed; they, too, were beheaded. The news spread like wildfire, and Bishnois from 84 villages gathered in Khejarli to join the stream of volunteers to protect the trees; 363 people sacrificed their lives, and the sacred khejri trees were saved.

When the king of Jodhpur heard about this sacrifice, he immediately issued a royal decree making the cutting of green trees and the hunting of animals within the revenue boundaries of Bishnoi villages a crime. To this day, the Bishnois take people to court for killing their sacred species—the khejri, the black buck, and the great Indian bustard. As Rajasthan is a fragile desert, ecological survival has been possible because of the conservation ethics built into everyday rules for the protection of life.

The forest thus nurtured an ecological civilisation in the most fundamental sense of harmony with nature. Such knowledge that came from participation in the life of the forest was not just the substance of the Aranyakas, or forest texts, but also of the everyday beliefs of tribal and peasant society. The ongoing struggle of the Dongria Kondh in Odisha to save their sacred mountain, Niyamgiri, from mining for bauxite is part of this ancient tradition.

Today, as the ecological crisis deepens with forest fires in the Arctic, floods in the desert of Ladakh, and in China and Pakistan, we can find renewed inspiration and a vision for the future from worldviews that see nature as alive and as the very basis of human life. We can thank Amrita Devi and the 363 Bishnois who sacrificed their lives so that the trees, the earth, and we, may live.

The above excerpt is from Vandana Shiva’s book Oneness vs the 1%: Shattering Illusions, Seeding Freedom (Chelsea Green Publishing, August 2020) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.