What if Women Designed the City?

I am convinced that the future of humanity and the biosphere will be decided by the way we choose to evolve our cities and towns in the 21st Century. Cities cover a mere 4% of the planet surface[1] but account for 80% of global energy consumption,[2] 75% of carbon emissions [3] and more than 75% of the world’s natural resources usage.[4] 4.2 billion people now live in cities and towns, and 3 billion more are expected to do so within 40 years.[5]

The case for cities adopting a beyond-sustainability regenerative approach is profoundly compelling. Pragmatic in their orientation, closely connected to the concerns of their residents, cities also contain the seeds of their own regeneration. However, historically cities have been planned, developed and built primarily through taking the male experience as the reference. As a result, cities tend to function better for men than they do for women.

A series of recent documents and reports by international ‘agenda holders’ [6] [7] and ‘knowledge brokers’ [8] [9] [10] reaffirm that the systematic exclusion of women from urban planning means women’s daily lives and perspectives rarely shape urban form and function.[11] Furthermore, what is known as gender-neutrality in urban planning usually adopts a male perspective, reproducing gender stereotypes and often limiting women’s realities to the role and function of carer.

There are two predominant perspectives informing the historic ‘urban planning gender gap’ debates which are concerned with the unique relationship between women and cities. The first perspective, built upon the premise of the fundamental condition of ‘vulnerability’ of women, investigates how historically cities restrict, disadvantage and oppress women. The second approach promotes the idea of urban environments liberating women, by widening their social-economic horizons and providing an escape of normative expectations. Since the predominant debates are framed by a dualist paradigm, with two contrasting, mutually exclusive realities, I intentionally redress the balance by proposing an integral perspective which includes and transcends this analytical divide.

Therefore, I suggest a perspective which is termed co-evolving mutualism. Here, women and cities are systemically implicated in the construction of each other in a continuous cycle of influencing and being influenced as women’s daily lived experiences unfold. This perspective acknowledges that contemporary cities can both limit and empower women, who in turn can contribute to a complex mesh of urban relationships and interventions.

In revealing these interactions, I view the relationship between women and the city as a single unbroken movement, generating life-affirming exchanges and supported by new patterns of thought and language. Furthermore, by adopting a co-evolving mutualism systems perspective, the pitfalls associated with adopting a zero-sum game perspective, where women’s gains are inevitably other people’s (men’s) loss, are uprooted from the ground up.

The book What if Women Designed the City? emerges from this unique perspective on urban development as seen through the eyes of women from different countries and diverse backgrounds who reveal multiple untapped potentials rooted in the uniqueness of their neighbourhoods. It is grounded in research conducted through walking interviews with 274 women seen as experts of their neighbourhoods from both affluent and hard-to-reach areas in three Scottish cities: Glasgow, Edinburgh and Perth.

Embedded in the richness of women’s everyday life in the city, the results are organised in 33 leverage points understood as places in a complex system where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything according to a framework developed by environmental scientist Donella Meadows. For instance… if women designed the cities, they would emphasise proximity over motorised mobility and active travel would be encouraged as a way of life. Green spaces would be connected creating nature corridors for wildness returning but also providing a continuous experience for residents of all ages to nurture love for living things. Safety would be prioritised by improving natural surveillance through neighbourhood watch groups and retraining those issuing parking penalties into community wardens who belong.

Key-Concept – Presency

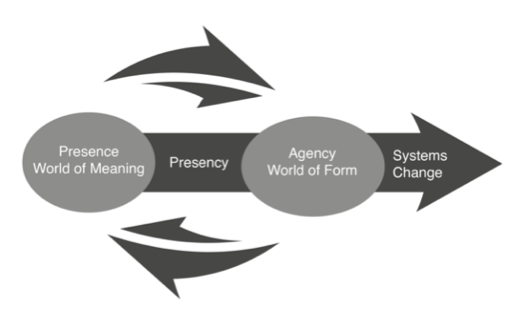

Humans exist in language.[12] It is in the spirit of languaging that I introduce a new concept termed ‘presency’, as a pathway for involving women and cities in processes of co-evolving mutualism. The concept blends the words presence and agency, combining both meanings. It adopts the concept of presence as a mindful way of paying attention to life, moment by moment, combined with agency, understood as critical awareness of the context and capacity to act.

For Paulo Freire,[13] reflection and action are symbiotic elements that support the development of a critical awareness of one’s social reality. Symbiosis here is understood as the interaction between two different living systems in close physical association, typically to the advantage of both. The emphasis on reflection over action leads to rhetorical verbalism, while action alone can only bear the fruits of shallow activism and limited positive change. It is not enough for women to come together in dialogue to gain knowledge of their urban reality. Critical reflection uncovering real predicaments improves their capacity to act intentionally and responsibly to transform their reality. Thus, the concept of agency adopted here is anchored in reflection on the present condition of the neighbourhoods in which women live, propelling them to co-develop purposeful new lines of work in their urban contexts.

By introducing the concept of ‘presency’, I acknowledge that profound changes in the urban environment, such as those aspired to by contemporary women, seldom emerge from ‘unrepresentative’ policy-making processes, nor from purely functional changes to urban infrastructure.

Transformative change springs from the dynamics between reflection and action, presence and agency, the realm of being and the world of function (also from disruptive and unexpected events). Within this perspective, women are understood as thoughtful actors who may transform themselves in the process of changing their environments.

Transformative change springs from the dynamics between reflection and action, presence and agency, the realm of being and the world of function (also from disruptive and unexpected events). Within this perspective, women are understood as thoughtful actors who may transform themselves in the process of changing their environments.

By centring the able-bodied, working male as the ‘neutral’ user of the city, modern planning has created urban spaces more suited for men – and often those white, healthy and wealthy – than for women, girls, people with disabilities, and sexual, gender and ethnic minorities. Embedded in the richness of women’s everyday life experiences of walking and living in the city, it is hoped that this work reveals unrecorded system interdependencies, widens the spectrum of planning participation and instigates new lines of work which together hold the power to change urban realities.

Jane Jacobs proposed that wholesale city plans never stirred women’s blood,[14] while De Beauvoir claimed that men cannot adequately represent women’s interests.[15] While planning was once the near-exclusive realm of specialised male experts, and in the 1990s communicative and collaborative methods became a prerequisite for planning processes, during the 2020s women are stepping up as protagonists in shaping their urban environments. In doing so, many are aiming to value their sense of place, care for their green and blue spaces, engage with an active travel world, and above all explore how cities of both the present and the future can be greener, wilder, more inclusive, liveable, and poetic.

Kosmos readers may pre-order the book What if Women Designed the City? 33 leverage points to make your city work better for women and girls published by Triarchy Press with the promotional code Kosmos23

Hard to believe, dear May East, that you don’t know Marilyn Hamilton’s huge work on cities.