Returning Home to Our Place in the Cosmos

The first time I wept for the Earth I was alone in the woods in late summer after a long run. It was, I believe, the combination of runner’s high, a sense of connection to the beautiful natural setting, and the culmination of several months’ personal awakening to the gravity of our ecological crises. I just stood there with my hands on my knees, crying in shock. It was a rare and surprising moment for me. The last time I had cried was at my grandmother’s funeral. But this time the grief felt immeasurably vast and deep, beyond anything I had ever experienced.

Standing there alone in the woods, I had the peculiar feeling that everything around me understood the moment I had just had. The flora and fauna knew my pain and welcomed (perhaps even with surprise) a human into the grieving process. There was a sense of solidarity and aliveness I had never experienced before in the world. In a way, I was not so much crying for the Earth as I was crying with the Earth. And it was a wholeness of being both bittersweet and euphoric, such deep connection intensified the bitter grief of life on a dying planet at the same time that it gave me a feeling of unparalleled aliveness.

This deep sense of communion with nature was a new and surprising experience for someone who previously held no such connection to the more-than-human world. As a white American male raised in a largely non-denominational Christian setting, my general experience had been to perceive no relationship with the environment beyond what it could provide to me for my own benefit. Trees made paper and firewood. Animals were for eating, sometimes pets. Rivers were for fishing, and mountains were for climbing. I was the product of a culture that does not teach empathy towards or reverence for the natural world, and these living phenomena had no intrinsic value or right beyond what they provide to human beings for our own wellbeing.

Such a profound separation from the rest of the natural world is not limited to my Christian experience. In reality, my entire cultural development growing up in Chester County, Pennsylvania, attending public schools and eventually college, all fostered within me what Thomas Berry might refer to as a “radical discontinuity between the human and the more-than-human world.” This process of acculturation had no one particular moment of initiation but was rather the ultimate outcome of myriad imperceptible micro-interactions that embedded within me a perception of separation from and privilege over the rest of life on Earth.

As a historian of world religion and culture, Berry perceived that all human societies have had origin stories that ground our identities in a coherent understanding of how the universe came to be and how we fit into it. These origin stories, which we could also call worldviews or cosmologies, explain the nature of reality and provide moral and existential guidance for the organization and development of culture over time. They are like the primary lens through which we perceive and relate to the universe around us, informing our actions and the values that determine them.

According to Berry, the stories that historically grounded us in the West have fostered an anthropocentrism that ultimately yielded the artificial separation of humans from nature that I was born into. Such a human-centered perception of reality, in Berry’s mind, eventually enabled the emergence of an industrial growth society that, within a geological instant, has created the social and ecological emergency in which we find ourselves today. Rather than reverence and reciprocity for the natural world of which we’re a part, modern culture is increasingly organized around consumerism and our ongoing alienation from nature that empowers it. This became a startling revelation for me: as a species, we had created a global system in which our own social progress had unleashed a force of planetary scale destruction.

On Coming to Genesis Farm

The journey to understand how the West could have arrived at such a place and, more importantly, how we might emerge from it, is ultimately what led me to spend eight months at Genesis Farm in Blairstown, New Jersey. Founded in 1980 by the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell, New Jersey, Genesis Farm has been committed to exploring new ways to address the sources of alienation that helped drive Western societies towards their destructive relationship with the natural world. Dominican Sister and co-founder Miriam MacGillis’ commitment to the seminal thinking of Thomas Berry has been a central foundation to the mission and programming of the farm, which has also served as a demonstration site and local catalyst for place-based, ecological alternatives to some of the industrial approaches used by humans to meet our fundamental needs.

I first learned of Genesis Farm through an interview with Sister Miriam MacGillis in Spiritual Ecology: The Cry of the Earth, Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee’s beautifully compiled collection of writings centered around the relationship between humans and nature. It was the first time that I connected a sense of spirituality to the Earth and the first time that I had ever encountered what felt like a satisfying integration of scientific understanding and spiritual wisdom; the ‘new cosmology’ suggested that the evolutionary journey of the universe, Earth, and humans could be seen as a comprehensive and inclusive foundation for human spirituality and meaning. Perhaps most importantly, such reflections also offered what felt like a root cause analysis of our present crises: social and ecological injustice at their core derived not from technological failures but from the very worldviews and stories around which Western society had organized ourselves throughout the course of our development.

Exploring a New Cosmology

From his perspective as a historian of culture and religion, Thomas Berry explored how the origin stories of the Greek, Roman, and biblical worlds held the seeds of an anthropocentric paradigm that ultimately helped create such an ecologically destructive Western human society. Berry thus called for a new story that could break through our perceived separation from nature and activate within us a renewed sense of reciprocity with the rest of life on Earth. Such a new story, he felt, could be provided by the scientific narrative of the universe, Earth, and humans told as a common evolutionary journey extending all the way back to the original fireball 13.7 billion years ago. This new origin story, with its insights into the ‘inner forces’ driving our industrial growth society, offered an unprecedented opportunity for grounding cultures everywhere in a new, shared context that would be universally applicable to all humans and all species, unlocking a renewed appreciation for the fundamental unity of all life.

Within our new cosmological context, the story of the universe itself becomes the primary frame of reference for reinterpreting the values that guide us and the cultural institutions that emerged from them. Such a new understanding of reality invites a paradigm shift in human consciousness, which, as I’ve learned from my time at Genesis Farm, is a reality that cannot be perceived from within the present context of understanding. The society that molds human consciousness today has not yet oriented itself within this new cosmological paradigm, which requires a transformation of identity beyond what our existing cultural response can provide us.

And so with this in mind, my time at Genesis Farm was an opportunity to begin learning the universe story as the deepest extension of my true identity. On the one hand, expanding my perception of self through time and space to the totality of the evolutionary process provides a sense of communion with the universe and Earth that has opened a vast new dimension of my own personal identity. Seeing the world through the lens of our new cosmology helps me understand myself as a participatory member of the entire process while also providing new energy and guidance for what Berry called the Great Work: transitioning human civilization to a mutually enhancing presence with the rest of the planetary community.

On the other hand, I am humbled by the task before us. We are very clearly in the midst of catastrophe. Climate change is no longer the looming threat I once anticipated dealing with at some point in the far-off future. It is here, now, accelerating every day, and poses an immediate danger to the most vulnerable among us. It is as if we have awakened from sleep to find ourselves chest deep in quicksand, sinking quickly, and nobody is coming to pull us out. In beginning to align my own consciousness with the long, developmental arc of the universe and its ongoing emergence, I am continually confronted by the unavoidable contradiction of living within the system that I am trying to transform.

Breaking through the Cosmology of Consumerism

Shortly after coming to Genesis Farm, I had a conversation with a friend who somewhat jokingly asked me if I had joined a cult. I laughed at his question, realizing that any photos of the ritual spaces or icons on the land might indeed present such a possibility. Thinking about this, however, I was struck with the realization that I had perhaps done the opposite. If anything, I had unplugged myself from the cult of consumer society that had previously captured my sense of identity and meaning. Grounded in both the scientific story of evolution and the diverse teachings of our many wisdom traditions, my experience at Genesis Farm opened new possibilities of direction and meaning in my life beyond the dream of industrial progress that had previously captured my imagination.

This has been perhaps the essential lesson I’ve taken from my time at Genesis Farm: that we humans have the possibility to awaken from what Berry deemed the ‘technological trance,’ a deep fixation and obsession for progress through technological development and unlimited economic growth. For if there is a shared cosmology today, it is the development of personal and community identity through participation in consumer society. The stories that once gave our lives meaning, whether they were Christian, Hindu, Islamic, or otherwise, are increasingly overwhelmed by the modern narrative of individual success and unchecked materialism.

I experienced this firsthand with my own family last Christmas. Watching my nieces and nephews rip open their gifts with the glazed eyes of an addict (which I also did as a child), I realized that Christmas Day now provides for many Americans what it once did to Christianity itself: the celebration of Christ has been replaced with the ritualization of giving and receiving an excess of gifts. The most significant holiday for Christian society is in reality an act of initiating children into consumer culture by teaching them that value is created through participation in this process.

While this experience certainly doesn’t speak for all (not everyone celebrates Christmas or has the means or intention to consume in excess), the corporate co-opting of traditional gathering times can be seen in various other holidays throughout the year: Valentine’s Day is for chocolate and roses; Easter for Easter baskets; and Thanksgiving, increasingly, for Black Friday deals. The historical role of such traditions is to ground human culture in the worldviews that shape individual identity and the larger development of social systems. That Western traditions are increasingly oriented around consumerism is a subtle but transformational shift in how we organize ourselves and our understanding of what it means to live here on Earth together.

Ritual as Radical Resistance

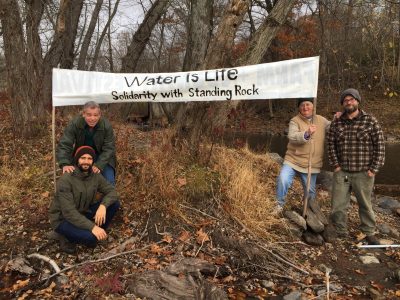

If we are to escape the technological-materialist trance that continues to grease the wheels of industrial growth society, then perhaps we need new traditions that cultivate a sense of membership in the cosmos and interdependence with the planetary community. At the time of my arrival, Genesis Farm had already begun the creation of a pilgrimage along the local Musconetcong River with a handful of other people in the surrounding watershed. As a part of this process, the body of water became the site for several small ceremonies centered around the violence inflicted upon both the river and the original Lenape people who had lived there for thousands of years before European contact. Inspired by Wendell Berry’s affirmation that “there are no unsacred places, only sacred places and desecrated places,” the rituals offered opportunities to re-sacralize the river while acknowledging and atoning for neglectful personal and societal behaviour that continues to this day.

Participating in these small ceremonies of direct communion with the river was an entirely new experience for me, the closest corollary being my participation in traditional Christian services as a child. But where before I had experienced a sense of the sacred abstracted from the natural world, here I derived a similar feeling through an immediate presence to it. Doing so activated within me a mode of consciousness whereby the river’s identity became elevated to a higher plane of value. Perceived through the lens of evolutionary time, the river had transformed itself in my mind from a human utility to a sacred reality with its own rights and intrinsic value.

In an era when it feels like everything is crashing down around us, the idea of ritual can seem trivial or even misguided. How will a small ceremony to honor the identity of the river help solve climate change or resolve racial justice? This was my initial reaction to the idea. What’s the point? After reflection, however, I began to think that perhaps such attempts to revitalize our relationship with the land around us might be the most radical acts of all. Given what appears to me as an ongoing and ever-increasing estrangement from nature, human efforts to reconnect with the planet in this way could offer a deep response to a culture that no longer takes responsibility for its membership in the larger community of life that sustains our civilization. Perhaps aligning ourselves with the evolutionary process itself is the most subversive response available in a culture so profoundly disjoined from the collective reality of our cosmic origin.

Returning Home to Our Place in the Cosmos

Reflecting on the story of the universe as the largest expression of my own identity has also awakened within me a new attention for the place in which I live. Such a process of cosmic rewilding grounds me in relationship to the natural context of my watershed, where I experience direct relationship with the ecological community to which I belong. Here I can enter into the story of a place not as an addendum or intrusion, but a participating member in its ongoing emergence. Reconnecting with place thus offers an appropriate context to care for the flora and fauna in a way that truly reflects the larger implications of our ultimate kinship.

It is at this scale, similarly, that we touch the entire universe, for every place is the place where we can experience the mysterious, self-organized dynamics that gave rise to such an overwhelmingly diverse and beautiful planetary community. In aligning ourselves with the wisdom of this process, perhaps we can finally emerge from our adolescence as a species and step into the responsibility that comes with our shared, cosmic identity. This is the potential of our New Story: that we may once again experience ourselves as welcome members of this garden planet, Earth, which is and always will be our home in the universe.

If you haven’t, definitely check out Charles Eisenstein’s writings on the New Story.

Hanna – Glad that you like Charles Eisenstein’s work too. We publish his work regularly in the newsletter and also occasionally in Kosmos Journal.

Indeed, Charles is a valued interpreter of the new story…!

Excellent article, Mark! Thanks for your work!

Many thanks Drew, you’re an inspiration for us all!

Mark. This is so beautifully articulated. Thank you.

Thank you Marianne!

Very beautiful and inspiring article, I have caught a deeper meaning for the word “ritual”. Thank you