Human Watershed: The Emerging Politics of Bioregional Democracy

The Crisis Downstream: Waiting For A Rainy Day

First, the bad news. Our global community no longer has the luxury of putting off its complex problems till a later time. Mounting data on Earth’s atmosphere confirm what is already known in daily life: the planet is warming and water is becoming less accessible.

Water scarcity is the result of climate change, diminished rainfall, overpopulation, inefficient infrastructure, over-pumping of aquifers, pollution and wasteful agricultural practices. Nearly three billion people around the world are experiencing periodic water shortages. It’s affecting people in southern and northern Africa, the Middle East, the nations of central Asia, China, India, Australia, Mexico and southwestern United States.

In coming years, water deprivation will spread to more areas, resulting in drought, food shortages, economic hardship and migration.

With this global crisis emerging, it may seem odd to explore stressed-out watersheds and their regional systems as a way of developing new ideas and policies. Yet this is also a moment for pragmatism. Ironically, temperature-driven civil strife and social displacement may lead to new approaches in the production and allocation of vital goods and services, leading to political reform, social stability, economic opportunity and international peace.

So here’s the good news. Humanity is rediscovering its commons: the self-organized management of resources which people need for their survival and livelihood. The ethic of commoning is based on the recognition that a person has the right to a means of sustenance without interference or harm from others. In this sense, the commons are an inclusive expression of the right to life and the right to justice.

Following the practices of locally-based commons, which have enjoyed a long and successful history around the world, decentralized groups at the regional level can also develop the means of governing their resources through negotiated rules and responsibilities for fair access and use. Bioregional democracy involves collective decision-making in the management and provisioning of the ecosystems that people depend upon for their existence.

The future of water-scarce nations lies in political restructuring, along with economic and educational advances that help them design this new landscape for regional accountability. Of course, bioregions occur within national perimeters, but there are also eco-regions which cross national boundaries. This is why watershed politics require a vision which embraces sovereign internationalism while reforming it at the same time.

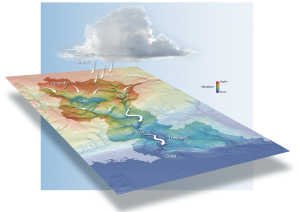

Courtesy of Arizona Department of Water Resources[/caption]Unlike liberal democracy, which favors individual rights within sovereign borders, a new set of rules and institutions is needed to balance the short-term interests of individuals against the long-term interests of all resource users within and across State boundaries. Bioregional democracy must be based on both individual freedom of expression and a respect for social differences in national and transborder communities alike.

This article does not deal with mitigation issues such as CO2 emissions reductions or geo-engineering. It focuses rather on adaptation—how civilization can limit its vulnerability to the impacts of climate change through the growing bioregional identity of citizens and the practical issues of resource cooperation and security which this entails. It also discusses how social diversity and resilience can lead to a new policy framework for consumption and provisioning in which energy and resource use are compatible with a limited biosphere.

Watershed: Linking Vision with Policy

Human Watershed is the story about who we are and what we do in a time of climate change and its turbulent effects. This new identity is already evolving, but in a diffuse way. It’s barely showing up in the media or in government or market activities. Global culture still lacks a cohesive theme or keynote to provide deeper insights and also create a link between these new ideas and social policy. What is missing is a compelling narrative with a few select images that reveal the relationship between social identity and social planning.

Modern citizens, particularly in urban areas, tend to forget that water is the ancient foundation of human settlement, biodiversity, agriculture, community, trade, culture and governance. Yet everyone can grasp these hidden layers of human history and civilization through a universal symbol—an effusive, dynamic watershed and its instinctual promise of rejuvenation and renewal.

While the metaphor of water flowing freely across parched areas is meant to inspire hope, it’s not unrealistic. A watershed gathers and spreads life-sustaining water, then channels it all into a single place. Society must replicate this process through sustainable practices for delivering water, food and energy to meet everyone’s needs.

Figure 1 – Watershed as a Framing Device for Ideas and Policy

| Personal Reality | Symbol | Bioregional Policy Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Self | Headwaters | Human Dignity through Bioregional Identity |

| Other | Waterway | Resource Cooperation through Transborder Communities |

| World | Sea | Regional Security through Sustainable Democracies |

Bioregional democracy is the provisioning of vital resources for all living things across areas wet and dry, agricultural and non-agricultural, energy-rich and energy poor. Diversity in the management and distribution of resources means opening up entrenched political systems and building capacities for the governance of ecosystems by the people who depend directly upon them. In this sense, the watershed symbolizes a strategic vision of regional pluralism and peaceful cooperation which satisfies people’s thirst for resource democracy.

The plot of this narrative involves the three stages of a watershed—the headwaters, the waterway and the sea. These areas correspond to three aspects of human reality—self, other and world.

- Headwaters are the source of a bounded water system. In a similar way, the self is the origin of a person’s higher intentions to respect and take responsibility for all life forms.

- Waterway is a course of water that sustains communities and natural things. Similarly, the other is a living reminder that people and nature are not separate but deeply interconnected.

- Sea (or river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland or ocean) is where a waterway converges after nourishing the life-forms in its watershed. Likewise, the world is where people can learn the natural patterns and methods for provisioning resources and designing sustainable ways of living.

Each of these images represents a policy area that is rooted in resource democracy (Figure 1). The following three sections elaborate on these themes and offer a new framework for bioregional cooperation.

The Self: Human Dignity through Bioregional Identity

Every life is sacred from conception to death. Respecting the lives of sentient beings is at the core of human existence. Human dignity is the basis of freedom, justice and social solidarity. But the reality is that very few people receive the respect they deserve. When individuals abuse power and wealth, they create imbalances with others in society. This is how human potential is suppressed and why human rights often do not deal with the fundamental reason for these disparities.

As modern history demonstrates, liberalism does a poor job of encouraging diversity and tolerating dissent. It has also missed the mark in ensuring the right to human sustenance through a clean and healthy environment, which creates even more imbalances between people and the Earth itself. The underlying cause of social dysfunction and ecological degradation is indignity—a failure to respect the other as oneself.

Let’s consider indignity in another way. One reason for the poor in society is a lack of education, which results in overpopulation. Overpopulation means that human numbers are exceeding the ability of humans to care for themselves. However, because decisions for the management of resources are outsourced to business and government, most people have lost touch with the actual sources of their physical nourishment and its means of provisioning.

Privatization, liberalization and deregulation in modern societies divide the citizens upstream of the economic current from those downstream. This creates social classes, asymmetries in wealth and theories like ‘prosperity will trickle down to the masses.’

Modern economics fully embraces the external world of sensory experience (through market price signals) but rejects the internal world of introspective and intuitive knowledge (by manipulating currency values and suppressing individual purchasing power). In simple terms, market-based rationalism denies the reality of human consciousness, emotional well-being and the empathic bonds which exist between people. Because of this behaviorist mindset, capitalism is unable to embody the idea that the life and dignity of every person must be respected and protected.

Disempowered by consumerism and unskilled in agriculture, generations of people have paid little attention to the capacity of their environment to sustain them, especially in relation to food and water. In recent decades, humanity’s neglect of nature’s carrying capacity has steadily increased. Most human beings are simply not connecting with their ancestral experience of doing what is necessary to preserve their lives and sustain their populations.

Instead, many individuals have come to believe that nature has nothing to teach them. The degradation of the environment, the inability to get the market to drive inclusive ecological solutions, the struggle to create peaceful and sustainable governments and to arrest mass migration—these all have their origins in people’s growing lack of capacity and authority for managing their commons.

Consider the problem of hydraulic fracturing—the injection of pressurized liquids and chemicals into holes drilled through dense bedrock. This technique creates small fractures in rock such as shale, allowing natural gas or petroleum to flow into the well before it’s pumped out for commercial sale and use. The process is damaging to the commons, especially its water and agriculture, and dangerous to the health of the people who live nearby (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Risks From Hydraulic Fracturing

- massive volumes of freshwater wasted

- surface water contamination from toxic chemicals, including carcinogens and radioactive materials

- increased methane and CO2 levels in the atmosphere

- contamination from spills

- health effects, including infertility, birth defects and cancer

- noise pollution

- seismic tremors and earthquakes

To regulate these fracking operations, which impact large geological areas, some local governments are developing legislation and zoning limitations. Yet this is not a widely coordinated effort. Public demonstrations over the risks of fracking are also increasing in the United States and Europe, but protestors have little political leverage nor formal mandate. Part of the problem is that individuals cannot compete with a prosperous industry that is sanctioned by government. Citizens are also conditioned to see the world through traditional political structures, leaving them with no serious legal framework or organized power through which to address the growing mismanagement of regional ecology.

In like manner, innovative approaches for resource governance are being developed in coworker neighborhoods, transition towns and eco-city projects, but there is little systemic connection between these and similar activities outside their districts. Individuals think mainly in terms of localities or national structures, while missing the regional commons which exist between them. This blind spot also extends to the capacities for ecological cooperation and governance which exist across national boundaries.

Regionalism is truly a new frontier. If the decentralized power and expertise of small-scale resource management were brought to bear regionally, the communities within a bioregional network could network and organize in new ways. People would reclaim and rebuild the capacity to manage their eco-regions, beginning with water and food.

After all, the most vital aspect of living in a human body is to sustain its digestive and reproductive systems, allowing individuals to nourish themselves, bear healthy children and recycle their waste to maintain life on the planet. Only then can our higher, creative capacities gain their full expression. But the care and feeding of human beings en masse takes education and collective action.

The bioregional economy offers an opportunity for genuine accountability in our patterns of consumption and restoration of resources, reconnecting us with the consequences of our decisions. When people actually know their aquifer storage and crop acreage yields, then they can calculate how much groundwater and food they can produce, the size of the population they can supply and how to absorb the associated waste.

Bioregionalism takes us beyond the Enlightenment beliefs about inherent rights which are guaranteed by sovereign governments. When the people of a bioregion are making decisions about the production and management of their resources, they are creating a conscious relationship with their regional water and food supplies. In essence, they are expressing the fundamental right of resource sovereignty, a freedom that is denied in liberal democracies.

Basing economics on the functions of nature means reversing the consumption of scarce and non-renewable resources. It also means provisioning energy and materials sustainably for everyone in society. In evolutionary terms, the dignity of bioregional identity is the birthright of every human being—the inalienable value which arises from natural rather than political boundaries.

Tolerance and a respect for diversity involve a deliberative, participatory process for the management of resources and a revitalization of the cellular memory that connects people with the Earth. Resource democracy thus has a basis in many spiritual traditions. The individual attempts to integrate the Divine into his/her Human Nature, and his/her Human Nature attempts to integrate itself with the Earth. This means uniting the individual with the collective identity not only through healthy social relations, but also by ensuring a more equitable allocation of resources and restoring vital human contact with the Earth.

Human dignity is presently at odds with policies which disrupt or suppress the ability of citizens to provide for their basic needs. This is why the socially marginalized and the poor must be included in policies which promote dignity and carrying capacity. In this context, the principle of responsibility to protect (R2P) is providing hope for the security of vulnerable resource areas by the global community, particularly when it encompasses the human right to sustenance and a healthy environment.

Ensuring that all people receive an equal degree of esteem and consideration is the foundation of a new belief system. Bioregional democracy offers a world of vibrant respect for life and a lasting commitment to justice and peace. By generating freedom, guaranteeing equality and building social cohesion—and developing the conditions in which these principles are no longer set in opposition as they have been under Western liberalism—human dignity will become the basis for a new culture of bioregional identity and sustainable citizenship.

Like the natural world of which we are a part, human beings evolve to survive and survive to evolve. In this way, human dignity is like the headwaters which are the source of biodiversity and community within a watershed. The sense of respect arising from bioregional identity starts an unbroken stream of social responsibility, empathy and care flowing through interpersonal relationships. This generates the conditions for resource cooperation across borders and enables human beings to express the evolutionary will to succeed on a collective scale.

The Other: Resource Cooperation through Transborder Communities

For more than two centuries, laissez-faire economics has promoted the idea that free trade leads to democracy and prosperity. This concept may have had some significance in earlier years when the world was less integrated. But in an age of global connectivity and global warming, liberal trade has lost much of its credibility. The present system of trade, based on the financial arbitrage of resources, does not benefit the poor, and is energy-depleting and harmful to the environment. On top of this, modern societies tax the value that people add to their commons, which generates further scarcity, poverty, waste and social and ecological debt.

It’s time for politicians and social planners to think collectively out of conscious choice, not from fear. We need to understand how painful and life-altering poverty is for those who suffer its ravages; but we must also acknowledge the historic failure of public institutions for the provisioning and regeneration of wealth in society. Water, food and energy are all sustainable if they are properly managed. However, most people are too busy consuming finite resources to spend time in planning how to use the natural cycles of Earth to regenerate their materials and energy.

With the fierce competition for resources worldwide, the boundaries of society’s political and economic systems are under increasing pressure from the boundaries of natural systems, species, food, water, energy, climate and culture. Through its present modes of resource management, modern civilization will not be able to sustain these natural resources indefinitely. For this reason, the principles of classical economics are being reexamined across the world.

The British economist David Ricardo (1772-1823) argued that a nation which can produce a good or service at a lower marginal and opportunity cost than another nation holds a comparative advantage. This is often simplified to mean that all trading nations will benefit when each one specializes in what it does best. With some qualifications, this concept has become the basis of modern trade.

However, the notion that all nations prosper through free trade is much disputed. In the debate between the global North and global South, a persistent fact is that comparative advantage benefits nations with superior technology over nations which specialize in agriculture. The American economist Paul Krugman has also shown that the transportation costs of goods and services often exceed the profits arising from their production and sale, erasing the trade-surplus bonus of Ricardo’s formula.

More recently, the ecological costs of global transportation have also discredited the principle of comparative advantage. When the world’s existing biocapacity is compared with the amount of biocapacity which people are presently using, it’s clear that trade-driven transportation is dramatically increasing the human demand on Earth’s ecosystems and their capacities for replenishment. Shipping natural or mineral commodities halfway across the world may provide a marginal benefit for producers, but leaves a costly carbon footprint upon the planet.

In coming years, the resources that we now waste, especially water and food, will become much less available. Without new economic thinking on wealth creation and sustainable development, free trade will continue to expand mass consumption and swallow the world’s natural resources. More fundamentally, society will be prevented from adjusting its economy to the world’s natural processes and designs, especially Earth’s hydrological and agricultural cycles.

It’s time to consider that bioregional self-sufficiency—the principle of meeting human needs within the constraints of resource areas—is really what leads to democracy and prosperity. Instead of seeking a Ricardian comparative advantage through global trade integration and rentier economies, the new social imperative will be for regions to become as self-sufficient as possible in the production and distribution of resources within their own eco-regions. Rather than maximizing total assets through a macroeconomic calculus, communities will focus on maximizing supply for the common good, producing and distributing resources according to the natural functions and rhythms of their environment.

Self-sufficiency means staying within the local or regional carrying capacity and taxing, not the value that people add to the commons, but the value they take from the commons. This creates dividends for citizens and the means of regenerating their resources. When people recover the capacity to sustain their population directly through the region where they live, there is no need to seek comparative advantage over the resources of others. Only when this is not possible would they look outside of their bioregion for trade.

The management of commons on a small scale has been successful throughout history because of interpersonal engagement. It’s easier for people to share resources when they know and trust one another. But technology-driven networks now enable the qualities of small-group dynamics to be applied in the collaborative management of much larger resource areas. This can be done without sacrificing personal trust, transparency or self-organized cooperation.

Just as the interests of corporations are not limited to a single nation, the social interest in an ecosystem is not confined to sovereign borders. Collective management systems may be created through communities of resource users, whether their ecosystems are within a single nation or spread across sovereign lines.

It’s important to remember that the members of local and regional communities are much closer to resource distribution problems than national governments, and a far richer source of local knowledge, innovation and ways of meeting human needs equitably and ecologically. For example, local communities have pioneered water management techniques like rainwater catches and drip irrigation which reduce water evaporation, and the recycling of household sewage for agriculture rather than publicly dumping the waste and polluting aquifers and wells.

What bioregional democracy requires is collaborative decision-making within a resource area. This is not such a novel idea. Identifying and building bioregional coalitions is a phenomenon that predates private property and sovereign boundaries. In fact, communities for resource management have historical roots all over the world, ranging from the Arab waqf, the Jewish kibutz and the Brazilian cooperative to the European guild, the English commons and the communitarian practices in hundreds of indigenous cultures.

While often unrecognized, transborder resource communities are rapidly growing. These include subsistence commons based on forests, fisheries, arable land and wild game; regional associations for the re-localization of food production, community-supported agriculture and permaculture; subsistence agriculture; seed-sharing cooperatives; and coalitions for irrigation and regional water access. There are also attempts to create collaborative resource management zones for the Arctic, the Amazon Basin, the Great Lakes of North America, the Jordan Rift Valley and the world’s wilderness areas, rivers, oceans and atmosphere.

In most cases, large-scale resource communities need the approval of their governments to work effectively. Through multilateral treaties and charters for the public benefit, the State may partner with these coalitions. This will allow transborder communities—comprised of civil society organizations, community associations, merchants, farmers, engineers, producers, professionals, educators and many other groups—to cultivate cooperative relationships and develop the legitimacy and mandate to leverage governmental policy. By organizing, they can begin to share power through stakeholder trusts and State trusteeships for collective resource management.

Here’s how this might work. The trust determines a specific, measurable cap to protect a resource for the future based on the preservation, consumption and regeneration of the common resource. The trust then leases an agreed portion of this resource to the private sector. Businesses extract and process the resources available outside of the cap, allocate and sell them as products, make profits and pay taxes to the governments of the region. The governments recirculate these funds to their citizens as dividends or subsistence income. And the trust spends its leasing income on the maintenance of protected commons and the replenishment of those resources that are depleted.

The capping of resources for future generations can also create a new source of monetary equity and credit. Regionally protected commons such as water, soil, forests, wildlife, seabed minerals, energy and indigenous patents may be used as reserves for a regional bank. This would generate a broad measure of sustainability that is not based on productivity, profit or interest, but on the resilience of natural assets in supporting a good quality of life and well-being for all citizens of a region.

A waterway is the rolling path that water takes as it nourishes biodiversity and community within a watershed, constantly renewing its landscape. In a similar manner, bioregional policies and their metrics can create an economic infrastructure in which the continuous throughput of resources fulfills people’s needs in equitable and sustainable ways. Society will learn from nature how to apportion materials and energy for all citizens by balancing the stocks (surpluses) and flows (deficits) of these resources. This enables the bioregional community to preserve the natural world, generate production, meet present needs, provide dividends, promote access to goods, regenerate the commons and create new sources of credit.

The World: Regional Security through Sustainable Democracies

Rising temperatures and extreme climate patterns are having an enormous impact on regional security. Global warming is resulting in the loss of species and biodiversity, decline of ecosystems, environmental hazards and natural disasters—all of which threaten human life, both in communities and wider areas (Figure 3).

Social Impacts of Climate Change (Figure 3)

- lack of water for drinking and irrigation

- declines in agricultural production

- higher scarcity of resources

- loss of supportive wildlife

- disease from mosquitoes and other pests

- declining health

- greater poverty

- increased migration

- volatility in production and trade

- economic losses

Ecologists study biological diversity to analyze a region’s carrying capacity and understand its natural resilience. Yet this is only part of what is needed. People must begin to use this information on carrying capacity to build social resilience. Besides broader participation in decision-making, this also means ensuring the civil protection and safety of these regional commons.

Until recently, the protection of resource communities has been more of a problem in countries with unstable governments. But all nations will soon be dealing with threats to bioregional security that result from climate change and its disruptive impacts. Along with the increasing acquisition of weaponry, the long-term preservation of commons is now the world’s leading security issue.

During the past two decades, the concepts of human security and responsibility to protect (R2P) have provided hope that regional solutions may emerge in places of conflict and war. Human security and R2P both rely on the existing system of intra-national sovereignty to provide public enforcement for the recovery and reconstruction of violence-torn societies and the rebuilding of fallen governments.

Yet from the standpoint of a bioregional community, sovereign security measures are not protecting vulnerable commons but often destabilizing them. The lack of access to common resources and public goods is the primary cause of failed commons, social inequalities and civil unrest. Neither human security nor R2P can substitute for a lack of accountability in the governance of people’s commons and the uneven distribution of resources in meeting their needs.

It’s the commons—not government regulation, military stabilization or even unarmed peacekeeping—that provide an authentic basis for effective resource provisioning at local and regional levels. In effect, when there is violent civil conflict, citizens are not uprooted from the arbitrary sovereignty of national borders so much as they are displaced from the actual resources of their bioregion. When the smoke clears and the dust settles, it’s the ecology which supports people’s survival and livelihood and defines their deepest sense of self and community.

As a source of non-violent cooperation between regions, the growth of transborder resource communities brings us well beyond present political boundaries. Yet this does not obviate the need for stable government. Liberal pluralism is an essential start: rule of law; maintenance of representative systems responsive to the people; the separation of powers among the branches of government; individual freedoms; the guarantee of equal rights for women and men; a free press; and the public legitimacy of government through free and fair elections.

Resource pluralism rests upon these rights. But bioregional democracy also focuses on the inclusive alliances of all actors within an ecosystem and the new class of rights which emerge from these relationships. These rights include human dignity; self-determination; economic and social development; cultural heritage; reconciliation of historical grievances; protection from sexual violence; protection for the uprooted; legal empowerment of the poor; human security; cross-border justice; rights to natural resources; rights to a healthy environment; intergenerational equity; the rights of children; and the rights of all living beings.

It must be emphasized that transborder resource communities are not secessionists. In creating the structures and conditions for bioregional pluralism, transborder resource communities are not seeking to instigate revolution but to act in partnership with their contiguous states. They promote a peaceful, cultural transition that does not reject what is being transformed, but demonstrates how to model and adapt to the new structures of resource cooperation which are emerging.

Resource democracy does not imply that sovereign states should stand aside or disappear. But they must expand the nature of their relationships with their neighbors through multilateral agreements and treaties which allow new forms of power and wealth to emerge in cross-border resource areas. There must be room for the creation of open platforms, proportional representation and diversified institutions by the people who produce and circulate their own resources within nations and between them.

There is evidence that the crisis of political succession in government—sometimes leading to failed states—arises from the inability of a society to provision resources and create fulfilling lives for its citizens within the boundaries set by nature. Closely-held natural resource endowments in sovereign states, particularly fossil fuels, are strongly correlated with domestic corruption, state repression and erosion of democratic ideals.

New research by organizations such as the Mumbai-based Strategic Foresight Group reveal another, much-neglected dimension of governmental stability. When there are resource agreements among nations which share bodies of water, agricultural areas or distributed energy networks, governments are more likely to create the conditions for regional peace. This, in turn, keeps these governments in power and responsive to their people, encouraging a stable process of political succession. It’s becoming clear that the orderly and non-violent alternation of political power depends on a government that is committed to resource cooperation with neighboring states as well as resource provisioning for its own people.

Global warming and its chaotic effects are providing some hard lessons. Nations cannot continue to divert rivers, over-pump regional aquifers and use water inefficiently without creating shortages in local communities, uprooting people from their commons and provoking violence. Present clashes over water may be only the beginning.

In 2014, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that, based on a projected rise of 2.5 degrees Celsius in atmospheric temperature over coming decades, the demand for water and food will rise but production will decrease. Governments can thus expect another wave of social unrest over escalating prices for water, food and energy like that experienced in 2008-2011. These conflicts could involve religious militancy, terrorism, open hostility between rich and poor, spiking inflation, high unemployment, national deficits and further destruction of the commons. Greater nuclear proliferation is also possible.

Before long, governments will recognize the advantages of redistributing the power for resource management. As citizens invest in their commons and the commons pay them dividends, the extreme competition for resources and the potential for violence will decline because the commons are available for everyone’s use. To make this possible at regional levels, institutional mechanisms must be created to share power within and across borders for the common management of resources.

This could take the form of confederations or associations for bioregional cooperation, especially in those areas of the world, like the Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia, which face political instability complicated by a lack of water and food. In turn, this could lead to the creation of Regional Cooperation Councils and the authorization of Bioregional Conventions which sanction partnerships between nations and their transborder communities for the sharing of resources.

The sea (or river, lake, reservoir, estuary, wetland or ocean) is where a watercourse converges after supporting life in a watershed. Upon reaching the end of its natural run, this water is released into a new cycle of activity. By applying the patterns of a flowing watershed, society can also develop accountable systems for the peaceful rotation of governmental power.

The safekeeping of resource areas requires the support of democratic governments which ensure political diversity in lasting and effective ways. Protecting transborder commons is not possible without governments which are credible and durable. Only sustainable democracies can ensure the public security which bioregional communities need to provision resources for present and future generations and to stabilize their consumption within the natural flows of the biosphere.

Returning Upstream: Our Common Frontier

The watershed—from its headwaters through the waterway to the sea—is really the story of ourselves. And just like the water supply, our narrative of economics, politics and culture is withering. It has not allowed enough inclusiveness in the management of our commons for concrete and sustainable social systems to come into existence and thrive. As a consequence, human civilization has failed to assimilate Earth’s natural cycles into its business cycles and we have lost our way downstream.

To discover what nature is teaching us about political and economic restructuring, we must return upstream to the springs of personal sustenance and social well-being. It’s really the power of values and ideas—not monetary wealth or legalized weaponry—that expresses our common understanding of what it means to be self-organizing, cooperative human beings.

Young people see the failed politics of water, food, energy and clean air and want to participate in changing this. They have a penchant for social action, for creating networks and engaging directly with communities. Youth will take part in electoral politics if it’s meaningful; and they will surely be creating the politics of the regional commons. Bioregionalism is their future. When the language and methods of bioregional cooperation become clear to them and this new political space is discovered, they will occupy it in masses, forever changing the scale of the areas in which resource allocation decisions are made.

Because the creation of bioregional pluralism is entirely new, planning and education are needed around these emerging forms of political diversity and social resilience. This will involve scientific and technological research, greater growth in knowledge-based industries and a flourishing of the arts in support of regional cooperation. Bioregional commons, involving trusts for water, food, energy and other resources, will also generate new forms of value in such areas as social media, communication, production, logistics, building and transportation. In practical terms, the multi-stakeholder governance of bioregions will become a prolific attractor of investment, jobs and prosperity.

All is possible, yet nothing is assured. The development of bioregional cooperation is a colossal, uncharted experiment in social self-organization. The only thing certain is that humanity is approaching a watershed. Who knows what will happen as natural boundaries eclipse political boundaries but the global community fails to develop its capacities for resource pluralism and resilience in social policy?

Our greatest challenge is not the risk of environmental collapse, resource wars, scarcity diasporas, oppressive rulers or rancorous disputes over why future generations are denied the opportunity to live in a peaceful and equitable society. Our true task is the creation of inclusionary institutions for sustainable resource production and provisioning as the climate crisis bears down upon the world.

[…] Excerpted from James Quilligan: […]

[…] all relate back to what I found to be the most meaningful things in James Bernard Quilligan’s “Human Watershed” article in Kosmos Journal: that being aware of the surrounding physical environment may be even […]

Really nice article. Thanks for contributing your ideas about how to restructure society following nature-based principles and systems. Inspiring and deep!

[…] Excerpted from James Quilligan in the ever excellent Kosmos journal: […]

[…] Excerpted from James Quilligan: […]