Earth-Based Wisdom: Learning the Original Idea from the Living Earth

Traditional cultures “are what shaped us and caused us to be what we are now,” writes Jared Diamond in The World Until Yesterday.1 All the necessities of modern living—electricity, store-bought food, pharmaceuticals, cars and planes—are relatively new. But much of yesterday is still with us, and we might take a lesson from those traditional cultures that remain indigenous to relearn how to live harmoniously with each other and the natural environment of which we are a part.

Since human societies have been traditional far longer than modern, could looking back provide clues for the future? What can we learn from our living ancestors that will help promote sustainability, health, and happiness? As we develop awareness of our common wealth, wouldn’t it be wise to take a lesson from those who long ago found a way to make society work?

A Reciprocal Mindset Fosters Balance

Four Arrows (Don Trent Jacobs), in Critical Neurophilosophy and Indigenous Wisdom, talks about “a returning in kind in order to maintain balance in the universe.”2 To be human is humbling and at the same time carries the greatest responsibility. This self-awareness requires of us to be conscious of our role in nature and our place in the universe. That necessitates mutual generosity—a reciprocal mindset.

To traditional people, life has meaning through family, community, and nature. But there is more. The reciprocal mindset that fostered sustainability over many millennia necessitated something other than people and land. The ability to abide for thousands of years demanded a deep understanding of the natural world and an unwavering commitment to universal, self-evident principles that originate from one central idea. From where does this understanding of an original idea originate?

In the West, knowledge is acquired in institutions of higher learning and wisdom is associated with experience, time, and age. Knowledge is an acquisition of information, much as is the accumulation of money, property, and goods. Wisdom garnered from lifelong learning is relative, a comparative process that provides perspective on past knowledge. But there are other kinds of wisdom. Innate intelligence is not one-dimensional, nor can it be easily learned. There is also wisdom that comes from oneness with nature, life, and the universe.

Among indigenous people, learning is passed down and passed on, and instructed mostly through example. Knowledge is not acquired; it is transmitted. In the indigenous mindset, pure knowledge is imparted though direct experience with the source of life—Nature and the Universe. An individual may embody wisdom, but its source is ancestral.

To the indigenous, wisdom is imparted from entities wiser than humans, including the highest mountains and the oldest trees. The wise person is a repository of memories, a keeper of learning, and a vessel for higher knowledge. The wise person shares knowledge freely with others in order to foster balance and promote harmony among people and nature. The indigenous way is reverential to a degree that Westerners might consider spiritual. Respect for the sacred in all things differentiates the indigenous reciprocal mindset from the modern Western mind.

In the often quoted address of 1848, Chief Seattle of the Suquamish people in what is now central Puget Sound in Washington state, alleged: “Every part of the earth is sacred to my people. Every shining pine needle, every sandy shore, every mist in the dark woods, every clearing and humming insect is holy in the memory and experience of my people. The sap that courses through the trees carries the memories of the red man. This we know: the earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth.”

Chief Seattle informed us that all things are connected, deeply rooted, ingrained with wisdom, and therefore sacred. Because we are children of the Earth, connected to each other locally and regionally—and more than ever as planetary citizens now—we are linked in one great planetary web of life. Indigenous people revere the Earth as the great mother who births all creatures and things. They see links and networks in nature as holy: trees are temples and mountains house intelligence. Why have modern people lost this sense of the sacred in nature? How can we get it back?

The traditional indigenous reciprocal mindset involves cooperation—giving so you and others can survive—but there is more. Indigenous people preserve an intimacy with nature that is in stark contrast to Westerners. They live a reciprocal lifestyle in cooperation with others and nature. The kind of reciprocity embodied in indigenous behavior fosters both immediate survival and long-term sustainability. Westerners are good at short-term profit and gain, but extraordinarily poor at foresight and long-term sustainability.

Chief Oren Lyons in Original Instructions says: “Life is endless. It just continues on and on in great cycles of regeneration.”3 Native American traditionalists like Chief Lyons hold that there is an original set of instructions, a natural law of mutual coexistence and sustainability. Sarah van Gelder of YES! Magazine referred to such a principle as “nature’s original idea”4 as she reminds us that sometimes nature evolves better ways for doing things.

The indigenous reciprocal mindset springs from an original idea that all things are biologically and spiritually interrelated and self regenerative. All things are created equal. The Earth is not only alive, it is a miracle. Nature is sacred. Life is truly endless. Nature is interested in a strong link between the past and the future. Evolution works because of an infinite number of such links. Keeping the balance of life through mutual reciprocity between humans and nature is the cornerstone of sustainability.

Ayni – Rediscovering the Sustainability Principle

Ayni is the Quechua word for nature’s original idea, the core organizing principle key to understanding the indigenous reciprocal mindset. Ayni is embedded in nature’s design. It acts as a golden ethical compass that always points true. Neither a religion nor a philosophy, Ayni is the guiding principle for a way of life that embodies ethical behavior and spiritual practice that promotes reverence for the Earth and heavens, family and culture. It fosters social harmony and engenders a common sensibility for all life — the sustainability principle, the original instructions.

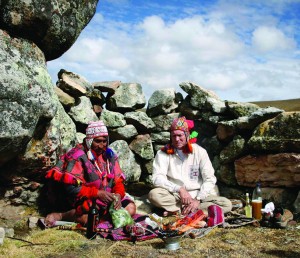

Considered living ancestors of the Incas and the keepers of traditional Incan wisdom, the Q’ero are a group of Quechua speaking indigenous people who live in a remote region of the Peruvian Andes. They taught me that Ayni is the touchstone of a worldview that holds it as the code of life. It is a blueprint discoverable in nature and ever present in the universe as the most useful and profoundly noble lesson that we will learn in life. It is the flow of energy co-created by the interchange of loving kindness, learning, knowledge, and the results of one’s actions. By practicing Ayni, one acknowledges that every thing is sacred and all things are related. Because it sustains and supports all life, Ayni requires conscious acknowledgement and willing participation to maintain the connection between the human and natural world.

Ayni requires of us remembrance for our place in the universe. It fosters humility, instills reverence, cultivates resilience. Like a kind of spiritual gravity, Ayni keeps things in their rightful place and assures that our children will have the same, if not better, opportunities than we have. During hard times, Ayni keeps things together. It reminds us of the responsibility we have, personal and planetary, to all dimensions of our lives, familial and universal. It promotes sustainability and healthy interdependence. In its purest form, Ayni is a state of mind. When the mind is attuned to the principle of reciprocity, it promotes happiness for oneself and others—the mind is at peace and the heart calm.

The Q’ero teach that Ayni is innate in the universe—a living principle that is intrinsic to life and springs from within us. In all my interactions and experiences with the Q’ero and other indigenous peoples, I found this to be the common theme. A golden compass, Ayni can guide our evolution. Can we learn to also use Ayni to better navigate our way to a sustainable, cooperative society?

More than reciprocity, Ayni also implies reverence and universal responsibility. Fundamentally, reciprocity requires healthy interactions. You give to me and I receive from you; later I give you something that you need. This is direct reciprocity. Indirect reciprocity is I give to you and to someone else, then someone else gives to you, and eventually someone gives to me. While the first type of reciprocity involves just you and me and is a common intercommunal practice among tribal people, the second type supports the evolution of cooperation within larger groups.

The Q’ero teach that Ayni resides within the human heart, an embodiment of an empathetic connection with nature and all creatures. Ayni occurs directly and indirectly between people and within groups, but also between humans and nature. We might do better if we were to introduce an entire new generation to the idea of an encompassing reciprocity that embraces universal responsibility and respect for all things, including every animal and the natural environment as well as the whole Earth.

Appreciating all living creatures as their relations, Native Americans believe that nature supports and sustains life. Shamans and medicine men maintain a two-way link between nature and humans through ritual acts of reciprocity; they have a unique affinity for communicating with the natural world. By ceremonial offerings of reciprocity, they assure balance between humans and nature. For example, the great mother that the Q’ero call Pachamama helps keep their alpaca healthy and herds large, makes birthing easier, brings rain at the right season, and promotes a healthy soil for abundant crops.

The Living, Conscious, Evolving Earth

By living among traditional indigenous people who embody the original idea,** it is clear to me that true sustainability requires a planetary ethic. Because it is a living wisdom, a whole planet ethic cannot be reduced to rules, is more than direct or indirect reciprocity, and is deeply rooted in empathy.

The Q’ero describe the natural world as a seamless interconnection between Pachamama and our bodies, and between the intelligence of the Apus (the tutelary mountain spirits) and our mind. Nature, wilderness, clean water, living oceans, and old growth forests are absolutely vital to heart, mind, and soul. Q’ero shamans received the original knowledge of Pachamama directly from the Apus and shared it with the people. Now they are sharing it with us, making it a living tradition. Each generation renews itself by direct contact with the spiritual energy of Pachamama and the wisdom of the Apus. Every aspect of life is interwoven in one seamless tapestry of cosmic order. With the Earth as the visible realm of Pachamama, everything in life is sacred.

Our living planet is but one of the many manifestations of Pachamama. The physical Earth is our biosphere, the envelope of life. In the greater sense, Pachamama is the divine feminine, the creative energy of the universe. We are part of a whole from the Earth’s core to the biosphere, upward to the heavens as one interconnected web of life and energy. All are part of this cosmic web of intelligent, living energy—plants in their sprouting, growing, and ripening; animals in their fertility cycles; weather patterns, ocean currents, and the transit of moon and stars in the night sky. Even human logic, emotion, and the unpredictability of human behavior are interconnected parts of one universal whole. From the calligraphy of clouds to bird song in the trees, the hum of dragonflies, humans laboring in the fields, and the stars overhead, it is all one hive of being and becoming. This encompassing worldview takes in everything terrestrial and celestial with humans playing an integral role between the microcosmic world and the macrocosm. Ever conscious of their place between heaven and Earth, the Q’ero favor humility in their role as custodians of Earth-based wisdom. They remind us that humans practice acts of reciprocity to stay attuned with Pachamama. For the Q’ero, Pachamama is the Universe: being and becoming, known and unknown, time-bound as well as transcendental. It is everything and nothing simultaneously. To appreciate the concepts of Pachamama and Ayni is to understand the indigenous worldview, the blending of time and life.

Emergence of Biospheric Consciousness

Over thousands of years, indigenous people came to a remarkable understanding of the natural world and a method of how to live harmoniously in it. Can we do the same?

Ishi, the last member of the Yahi tribe of the Sierra Nevada foothills, turned himself in to authorities in Oroville, California in 1911. Ishi was the last known American Indian to be raised isolated from Western culture. Saxton Pope, the American doctor, teacher, author, and outdoorsman who formed a close relationship with Ishi, wrote: “Ishi looked upon us as sophisticated children—smart, but not wise. We knew many things, and much that was false. He knew nature, which is always true. His were the qualities of character that last forever. He was kind; he had courage and self-restraint, and though all had been taken from him, there was no bitterness in his heart. His soul was that of a child, his mind that of a philosopher.”5

Global Systems Thinking

Global system change demands new thought, but planetary transformation requires nothing short of a new ethic based on universal responsibility and cooperation that is rooted in nature—a whole planet ethic. What’s needed is pattern changing on a grand scale, principle to connect them all, an agreement to find common ground. We might begin with a fuzzy low pixel concept like reciprocity and the idea of a living Earth. It’s useful to learn a new term like Ayni. But it’s only a start. We have to proceed creatively and with keen observation, increasing the resolution of our vision until a singularity occurs. From time to time, a truly powerful idea emerges, and in a single clarifying moment, our thoughts and emotions crystalize into a perfect whole as if the puzzle solved itself.

We’ve brought the great problems of our times upon ourselves. Our problems are uniquely human. Animals would never disown other members of the same species or negate the status of other living animals. But we equate animals as non-human, having no rights. We commonly deny other people their humanity, which may be one of the biggest obstacles to a collaborative society.

Humans are the creators, producers, and consumers that have developed systems that greatly benefit a few and cause great harm to the many, including the biosphere. How will we get from the verge of catastrophic collapse to a saner, healthier, freer society that allows for the renewal of nature? Every journey needs a compass. We will soon leave behind known terrain and enter uncharted territory. When that happens, we’ll need to be able to find a pole star by which to navigate the rest of the way.

Our future depends on a spirit of generosity, universal responsibility, and the commitment to do what’s right for the planet, not just individual accumulation of capital, goods, and property. Our best option may be to learn directly from those who still embody the secret of living on the Earth with zero footprints. We might do well to look backward in order to lean forward.

We need exponential thinkers that can envision ahead not just fifteen or fifty years, but one hundred and fifty years into the future while looking back, holding to the original instructions. We need deeply heart-centered, compassionate leaders to teach us how to relearn how to live on this living Earth.

Note: from a book in progress, Whole Planet Ethic, to be published in 2016.

**I first lived with the Yupik people of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea in 1967-68 and most recently with the Q’ero of the Peruvian Andes from 2000 up to present. In between 1969-1996, I formed close relationships with North American medicine men and conducted fieldwork among indigenous and mestizo immigrants from Mexico including field trips to Oaxaca in Southern Mexico where I worked with the Zapotec. My gratitude goes to these Indigenous people who taught me Earth-based wisdom. jewilliams@ayniglobal.org.

References

1 Diamond, J. (2013) In The world until yesterday: What can we learn from traditional societies, p. 512. New York: Penguin Books.

2 Four Arrows, D (2009). Critical neurophilosophy and indigenous wisdom. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

3 Oren, L. (2008). Original instructions: Indigenous teachings for a sustainable future. Rochester, VT: Bear and Company

4 Gelder, S (2012). To change our direction, it’s time to follow nature’s lead. Yes Magazine www.yesmagazine.org/issues/what-would-nature-do/natures/original-idea

5 Kroeber, T. (2011). Ishi in two worlds Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Excellent article reminding us that “Everything in the universe is both an input and an output” in all processes, including man; that processes never quite end; that nature, at any particular time, seeks and finds equilibrium, and that it does so asymptotically, however brusquely a process may begin, through flows from abundance to scarcity; that equilibrium must be conserved or restored for planetary health; that in view that resources and opportunities for their use shall always be scarce in relation to perceived needs, conserving or restoring equiilibrium requires avoiding unncessary or detrimental changes in human habits of all kinds, but rather the opposite, including in production and consumption, and restraining the multiplication of any species to the detriment of others, including mankind; that ultimately, from a current human perspective, wisdom lies in the use of knowledge for the planetary common good.

I strongly agree that we need to shift our perception back to seeing ourselves as an integral part of a living, conscious Earth. I am optimistic about the emergence of biospheric consciousness.