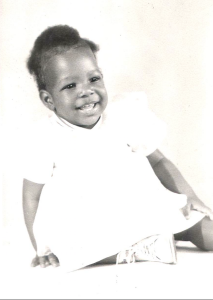

Diary of a Watts Princess: A Memoir of Hopes and Dreams

I love my father so much that if someone asked me “how much?” I couldn’t explain it. I feel about him as e.e. Cummings did in his poem “If There Are Any Heavens.” Mainly the part that says, “If there are any heavens my father will (all by himself) have one. It will not be a pansy heaven nor a fragile heaven of lilies-of-the valley but it will be a heaven of blackred roses.

~ Tamara Smiley, February 21, 1968 (English 10 Journal Entry, Washington High School, South Central Los Angeles)

It was a Wednesday I will never forget. A funny frenzy is in the air that hot August night of 1965. A restless energy moves down the block just before nightfall. The heat is unbearable, so people are sitting outside on their front porches, fanning and sipping ice water. Some kids play catch while some do Double Dutch jump roping. News snaked through the block that there was a big fight going on at the intersection of Avalon and Imperial Highway, not too far from my sister’s house. The California Highway Patrol had stopped a car and tried to make an arrest. The crowd gathers larger and larger until Mrs. Frye, the mother of the man being arrested, hits the cop to stop her son from going to jail.

Tempers that had been smoldering for decades just explode into the summer night. While chaos was brewing at Avalon and Imperial Highway, it was also spewing over on 103rd Street and Compton Avenue. A group of young men who normally occupy the vacant lot next to a hardware store—just talking under the moonlight—must have felt the tensions oozing throughout the tiny town of Watts. A brick hurls through the window of the closed hardware store and ushers in another wave of violence that hot August night. Even though everything was spontaneous from decades of smoldering rage centering on a lack of everything—a lack of jobs, opportunities, programs for kids during the summer—the first brick opened the door to an all-out scene of rioting and looting. Sirens sound like background music in a bad soundtrack. I stand on my front porch watching neighbors running, excited that we were there when it ‘went down.’ I wasn’t sure what ‘went down,’ but the block took on a carnival atmosphere. Men opened the trunks of their cars showing off the ‘loot’ they had gotten from 103rd Street. That was considered downtown Watts. On 103rd Street, a person could buy everything from clothes and shoes to hardware. It was our commercial district if we didn’t want to ride the bus to the real downtown Los Angeles at Eighth and Broadway.

All of a sudden: the sound of breaking glass.

“They hit the liquor store!” rang down the block. The liquor store was a staple of the neighborhood for more than just liquor. A kid like me could go in and buy a soda, candy, and ice cream. Just twenty yards from my front door, the liquor store was truly a convenience store when my mother needed milk or batteries. Harry’s Market was around the corner, but she could see me go into the store and watch me walk back down the street.

When the glass broke that night, I felt something scary was creeping to my neighborhood. It was as if television narrowed the distance from the disturbance on Avalon and Imperial Highway to my block. More glass breaking shattered the night.

“You better hurry up and get something!” Young and old were running to and from the liquor store. The adults ran with boxes and crates. Kids had boxes of ice cream melting in the hot August night. I can still see them sitting on the curb across the street from my house, gorging themselves on melting fudgesicles and ice cream sandwiches. For many, the freezers were full of looted meat, so there was nowhere to store the ice cream.

The next morning, the “What you waiting for?” seemed to come out of nowhere as the traffic to the liquor store built to a steady stream of comings and goings. Some people laughed like it was party time. Others had serious looks as if they were all business—taking what was due to them, taking the injustice endured since many moved from the segregated south. For many, the land of milk and honey they thought would be their ticket to economic prosperity and home ownership had turned out to be a false promise.

It was ironically funny how one group’s misery can be another group’s opportunity. When the Japanese were forced into internment camps during World War II, they left good jobs and homes in Los Angeles. The industrial machines felt their loss. Black people in the south, waiting for a break, responded to the news that there was work in Los Angeles, that schools were good, and the sunshine lasted a long time. They quickly transformed South Central Los Angeles into their own communities on the east side of town. Growing up, I did not realize how historic my old neighborhood was at 23rd and Hooper Avenue.

Years later I would learn that all of the Black Hollywood and music artists played on Central Avenue at the Lincoln Theatre. Big-name entertainment was right in my backyard because that was the happening area for Black people seeking to be entertained and the artists hungering for an appreciative audience with whom they could relate. Those were the days when big-name entertainers like Lena Horne and Sammy Davis Jr. could sell out a major venue, yet they still entered and exited through the kitchens and back doors. Since they could not stay in White hotels, Black aristocrats—like the architect Paul Williams and the attorney Hugh Macbeth, a Harvard lawyer who set up his practice at 82nd and Broadway and who would later hire the first female attorney in Los Angeles (a White woman)—provided overnight accommodations and hospitality to the entertainment elite. When your city is burning, all kinds of memories and associations come flooding in and cascading over the here and now.

“Serves him right with them high prices.”

“He just comes in here and takes our money back to his community.”

“It’s about time!” echoed down the street.

My excitement overflowed from the view of my front porch. I walked down the walkway to the sidewalk for a better view. All I can remember thinking was “This is crazy! Everybody’s gone crazy!” This felt like a block party, with kids sitting on the curbs still trying to eat as much ice cream as they could while it melted in the hot August night.

I had seen enough.

“Mama! They broke into the liquor store!” I yelled over my shoulder. It got to be too much for me to watch as a passive observer when all of my friends were giddy with their boxes of melting ice cream sandwiches and multi-flavored popsicles. My brothers sat with me with the light of the night shining in their eight- and six-year-old eyes. They were taking it all in, too.

“Mama! Can I go?” was probably the most ludicrous question I had asked up to that point in my thirteen-year-old life. Yet, because everybody else was doing it, I actually expected her to walk outside and watch me go to the liquor store and steal ice cream, sodas, and candy, which I could easily have covered from the money I saved and wrapped in a handkerchief in the back corner of my underwear drawer.

I don’t remember her exact words. I’m glad I don’t have a memory of the scowl that was across her face. All I know is she told me to get back up on the porch or come inside for the night. I pouted so much that I ended up missing the rest of the street show until I could remember who was running this house.

I took my view to the back-porch steps. Standing there that Wednesday night, August 11, 1965, I probably knew deep down inside that my life would never be the same. I didn’t know how. I just knew that everything was different now. If we needed milk in the morning, there would be no place to go close by.

The night sky lit up like a big firework. Oranges and reds sparkled in the sky. Sirens seemed to be everywhere. Gunshots scared me so bad I thought the world was exploding and I would be nothing but one of those embers floating like fireflies in front of my face. I remember brushing them away from my face, hoping my hair would not catch fire. I had smelled burning hair when my mother’s hot comb was too hot. The sound of my own hair burning and the smell in my nostrils was enough to convince me I did not want a ball of fire tumbling down on my head.

Even today, the only feeling I can vividly remember was one of fear laced with excitement and anticipation. What was going to happen to me? Would I burn in the fire coming closer to my back porch? Would that burning smell of buildings smoldering in the night stay forever locked in my entire body? I remember looking up into the black sky on fire and asking God to save me, to save my house because it was the only one we had. I don’t know if God answered me right then, but a feeling came over me. It was a feeling that told me I had a lot to do in this world, that the fire was a sign of something big. Years later, I would read James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time and be reminded of this night. That hot August night, I knew God had a purpose for me. I was too young to figure it out then, but I knew in my bones as I fanned the embers and watched Watts burn into the night. It would not be until morning news that I would get a fuller picture of what was beneath those flames. I had no idea it would last six days, that 34 people would die, that 1,072 would be injured, and that 4,000 people would be arrested in a small space of a community.

I heard my daddy call my name. He was coming in the front door as I came back inside from the back porch. He held out a gift for me. It was a transistor radio he bought for ten dollars from the neighbor across the street. It was the only souvenir I would have from the bloodiest battle in an urban neighborhood. I took the radio and put it in my room. For the next five years, it would wake me up to go to school. But for now, I would be able to listen to the Magnificent Montague, the local disc jockey whose signature phrase long before the rebellion was:

“Burn, baby, burn!”

What happened in Watts those six hot August nights forced me to think about my identity—who I was and who I was going to be. I have never had an identity crisis—or so I thought. You know, that heavy feeling of not knowing yourself, who you are, or where you are going in this world.

As I watch the news today, old feelings of fear and hopelessness engulf me once again. As a thirteen-year-old girl, I saw my neighborhood, Watts, burn. Then I wondered what would happen to my home, to my life, as embers from the fire floated in front of my face. I wondered who I would be if I lived through the chaos of urban anger and despair. That night, I wondered what my purpose in life would be.

A few years later, that purpose became clearer. In 1968, the National Council of Christians and Jews brought a multicultural group of high school students to the Brotherhood/Anytown Camp in the Idyllwild Mountains. I lived and worked with kids from all over Los Angeles to create a better world. With cities now burning across the country, we had one blissful week of working together to solve race relations. We elected officials, wrote empowering governing articles, and heard each other’s stories. Each night we sat around a blazing bonfire, locked arm in arm and sang songs of freedom, hope, and resilience. The late Clabe Hangman played his guitar to “Blowing in the Wind” and “If I Had a Hammer.” We were from many walks of life and we were learning how to be with one another. It was the first time I ever danced with a White boy, a slow dance. It was also the time when the boys from Jefferson High School and members of the Black Panther Party threw me in the pool on day two, causing my hair to go natural for the week. When I returned home, I trimmed it and wore my hair natural up until today.

It was on that mountain that Nancy Trask, a White woman, saw me, really saw me. We often walked back to the dining hall for lunch after hiking or some outdoor activity. Little did I know, she was interviewing me for Scripps College, her alma mater. When my father died when I was in the tenth grade, my counselor, another Jewish woman, saw my grief and had me work as her office assistant. With my heart set on Stanford, USC, or UCLA, she recommended the small, selective women’s college, the alma mater of Nancy Trask. The next year, I received a four-year scholarship.

Even as I entered college in 1970, the fires of Watts still smoldered inside of me. I had this burning desire to try to figure out this race thing, the what and why, the impact. I majored in Black Studies at Scripps College and received a master of arts in African Studies and Research from Howard University. I spent a semester of my senior year in Ghana, West Africa. Visiting the slave castles at Elmina and the Cape Coast deepened my knowledge and expanded my perspective on race relations. When I lived in Germany, I visited concentration camps and the home of Anne Frank in Holland.

Little did I know that all of these experiences prepared me for the times we are experiencing today. The fire from 1965 still resides in my belly. But unlike the young girl who watched powerlessly, I know that I am equipped to build bridges across the deepening racial divide. Today, as a professional speaker and coach, I support organizations in addressing issues of diversity, bullying, and macroaggression—which many see as the new face of racism. I believe that through conversations on race and differences, we can find the common humanity that binds our hearts and minds.

Learn more about Tamara’s work at Audacious Coaching, LLC.

What a great story from a great lady! Your eloquence with words mirrors your elegance in life.

No words to express the inspiration received from your story. Please, continue to share with the world!

Love, Sistah Wilma Ardine