Sacred Diplomacy in the Emerging Ecozoic Era

In a speech in Rome on World Food Day, October 16, 2018, David Beasley, Executive Director of the U.N. World Food Programme, sent out a global warning: “A potent combination of hunger, climate change and man-made conflicts are creating a ‘perfect storm.’” The U.N. also reports: “After a decade of decline, the number of chronically malnourished people in the world has started to grow again—by 38 million, largely due to the proliferation of violent conflicts and climate-related shocks,” and that “child labor, after years of falling, is growing, driven in part by an increase in conflicts and climate-induced disasters.”

Early in 1994, I stood weeping under a full moon on the banks of the Neretva River, mourning the loss of the historic Stari Most bridge, blown up by the Croats in Mostar, Bosnia, the scene of some of the worst fighting during the war in Bosnia. The collapse of the bridge and the pollution of the river was a symbolic blow signaling the final destruction of the cultural heart of the city, named after its bridge and spiritually tied to the river that had flowed beneath for almost five centuries.

Divided by ethnicity and war on opposite sides of the river, courageous Croat and Muslim mothers (the city devoid of all but a few very elderly men) met with me to negotiate a joint plan to restart deliveries of yogurt, milk, and juice to children surviving on both sides of the besieged city. The deliveries had stopped with the Serb bombardment, and the children were hungry. During those meetings—in underground shelters safe from the constant shelling and sniper fire—I said to myself: Somehow there has to be a way to transform our old models of conflict resolution and diplomacy, because something is clearly not working any more!

A decade later, I was invited to mediate back-channel negotiations among Middle East water ministers trying to figure out how to share dwindling water resources more equitably. At some point in the discussion, a Lebanese delegate made a suggestion that the effort to reach agreement on a cooperative structure was like building a house, and maybe we should “begin in the basement.” One of the Israeli delegates, a wise elderly man, rose from his seat at the table and—visibly shaking—cried out, “We can’t begin in the basement, because the basement is full of blood!” The other delegates were shocked, and I, the mediator, as has happened too frequently in my career, had no idea what to do next. Sensing my distress, the Israeli minister, now seated, sought to reassure me. Referring to the genocide of European Jewry, he said, “Don’t you see, my dear? The Holocaust made us crazy!”

A new craziness is rapidly descending upon us as the result of the ecocide of our planetary home and its populations. Global trauma resulting from violence, displacement, ecological collapse, and migration, alongside cascading climate catastrophe, demands new and urgent diplomacy as our planet transitions from one epoch to another.

We must transform diplomatic process to meet the growing crisis of climate-related conflicts laid out in the UN reports. Optimistically proposing the coming Ecozoic epoch emerging from the present Cenozoic epoch, Thomas Berry writes, “We need to go further into that deeper identity that we have with each other in the Great Self. Somewhere, somehow, mercy and justice must kiss in the all-embracing numinous presence wherein peace descends upon us all in the dawn of a new day.”

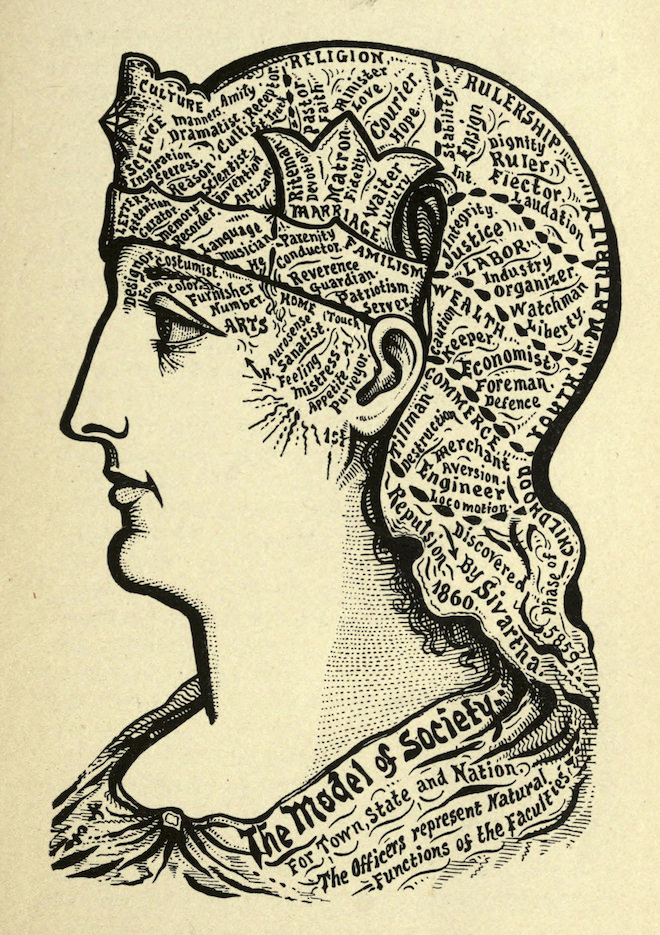

In his book Native Science, the title a metaphor for timeless Indigenous knowledge, Professor Gregory Cajete, Tewa from Santa Clara Pueblo, has captured an exploratory and exciting synthesis that emerges from the two ways of knowing—the experiment and the experience. He writes, “A new scientific cultural metaphor has begun to take hold. The insights of this new science parallel the vision of the world long held in Indigenous spiritual traditions.”

Even though Western science searches for knowledge through experiment, and Native science through experience, at the heart of both cosmologies is the principle of nonlinearity. We students in the West, separated too long from Nature, are still largely taught to think in linear ways: one cause produces one predictable effect. In complex systems like a classroom, a city, a nation, a universe, one cause—even something very small—can have multiple, mostly unpredictable, and sometimes mysteriously large unanticipated effects: the hummingbird flapping her wings in Brazil affecting the vortex that brings a massive hurricane to Florida.

What if traditional global diplomacy used the principles of complex dynamic systems to transform the possibility for a just and lasting peace in our universal valley?

Weather and ecosystems are complex systems, as is most of Nature. Indigenous wisdom recognizes that we are an intimate part of the flow of nature’s life-giving forces. We are in relationship with the give and take of nonlinear evolutionary change. On the other hand, linear causal thinking (Newton’s clockwork universe), while important to basic engineering and technology, often leads to the false assumption that man can control the dynamical, constantly adaptive flow that defines the natural world.

This false assumption has led to what many of us call the ‘Domination Code,’ the futile and exploitative human activities that attempt dominion over Mother Nature and her children. I once watched the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers beat a hasty retreat from constructing barriers to protect a community built at the base of Kilauea, an active shield volcano in Hawaii rapidly pouring lava over the pointless and futile barriers. The latest excitement over geoengineering to tame climate disruption sadly continues the same vain, and dangerous, thinking.

If we emerge into the Ecozoic era that Berry calls for, one that commits us to “a new mode of human-Earth relations, where our response will reverberate through every future epoch,” there will be an important role for global citizenship in a new sacred diplomacy that mirrors the momentous shift from dominion to relationship; from separation to participation; from dualism to Spirit; from violence to blessing.

Rev. Joni Carly suggests that there are “white spaces” in between advocacy for policy and spiritual messaging, and that global citizens have a responsibility to promote peace in the “spiritual space.” Postcolonial studies scholar, Homi K. Bhabha would agree, defining a “Third Space” that “displaces the narrative of the Western written in homogeneous, serial time.” These are liberating spaces to meet where political and cultural differences have the opportunity to dissolve into transformative peacebuilding.

International diplomats are worn out from the toxic politics, overriding militarism, and positional bargaining for land, money, and power that define present negotiations. The twin existential threats to planetary survival—climate change and nuclear rearmament—demand a new sacred diplomacy based on processes that mirror the dynamics of living systems led by a more inclusive, feminine, and newly empowered global citizenship. The content soars when the process includes diplomatic meetings that start with no pre-set agendas specifying linear outcomes; that are designed in circular settings to encourage spiritual reflection and listening as the basic norms of dialogue; that respectfully navigate both positive and negative feedback loops as discussion deepens; and that insist on a holistic analysis of issues previously sliced and diced into separate categories.

Finally, global citizenship offers a holistic model for diplomatic encounter and a peacebuilding process that facilitates an emergent creativity and discovery of the “adjacent possibles,” solutions for our present dilemmas that appear out of the shadows as debate becomes agreement and adversaries become a “noetic polity” that William Irwin Thompson describes as “the shift from the economy of men to the ontology of angels.”

Today, we are shifting from a worldview that is obsolete – obsolete because it is just not working anymore. It is a mechanistic, reductionist worldview of separation, fear, survival of the fittest, win-lose, and exploitation of nature and one another. The one emerging is a holistic, organic worldview of connection, cooperation, win-win, and kinship with nature.

— Foundation for Global Community

Thanks for articulating this so well, David, and for your support of Kosmos. We are grateful to you.