Bioregioning and Our Felt Sense of Place

Editor’s note: This feature is derived from Bioregioning 101 with Nate Hagens, a Reality Roundtable. Kosmos has edited the original transcript for the sake of clarity and readability with permission of the speakers.

Nate Hagens: So I thought we would start with an introduction to bioregioning. What is it? Why is it important? And why is it relevant to our future?

Isabel Carlisle: Bioregioning is something that humans and early pre-humans, hominins, have done really since the beginning of time. It means living in a place, understanding that you’re part of the natural systems of that place, and, in a sense, working with those natural systems. We might get onto this later as well, but, for instance, Neanderthal people knew where their food came from, where their herbs were, where their water was, where their stones were, and what kinds of trees were growing what.

Isabel Carlisle: Bioregioning is something that humans and early pre-humans, hominins, have done really since the beginning of time. It means living in a place, understanding that you’re part of the natural systems of that place, and, in a sense, working with those natural systems. We might get onto this later as well, but, for instance, Neanderthal people knew where their food came from, where their herbs were, where their water was, where their stones were, and what kinds of trees were growing what.

So, they were kind of thinking in systems, and they were thinking as part of the natural world. While the bioregional movement went through what I would call a slightly romantic phase back in the 1960s and 1970s on the northwest Pacific coast, I would say that this latest iteration of bioregions and bioregioning—how you do it—is really about getting to grips with existing power structures, politics, economics, climate change, and all the challenges and ills that we’re facing.

Some people see it as a response to the polycrisis because it embraces everything. It covers ecologies, economies, human health, and the health of our biosphere.

Nate: Well, I have a historical speculative question based on what you just said. I don’t know how much you know about my work and the idea that humanity has outsourced its wisdom to the broader financial system. We’ve become this globally interconnected economic superorganism that blindly consumes energy and ecosystems. But let’s speculate for a moment: if this global economic system didn’t exist, would a pro-social, benevolent, alien philosopher visiting Earth find humans naturally organized by bioregions? Without all the fossil input and everything we’ve done, is that the natural default state of how we would self-organize?

Isabel: Yes. Obviously, I know more about the United Kingdom than other parts of the world because I’m from here—but you only have to look at the native accents that existed a hundred years ago in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and England to understand how regional our lives were. And yes, it was bioregional, because what we produced in each place, the kinds of food we ate, and the trade we engaged in were entirely localized within our bioregions.

We haven’t actually described what a bioregion is yet. It’s a coherent geographical entity—a landscape—not politically defined. It has coherent geology, landform types, fauna, flora, rainfall, and human history, including economic, social, and political history. So, there’s a coherent story that runs through all these layers. When we think about the kinds of “islands of coherence” or “lighthouses” we need to move forward as a species, bioregions provide that cultural grounding—what was historically true and what we need for the future.

Daniel Christian Wahl: Here is something my mentor, David Orr, said 20 years ago. He described fitting a species arrogant enough to call itself Homo sapiens onto a planet with a biosphere as a design challenge. He said we needed a form of ecological design to address it. This Homo economicus you described, blindly consuming everything in its path, is a maladaptive pattern that seems almost cancerous to the living system.

Daniel Christian Wahl: Here is something my mentor, David Orr, said 20 years ago. He described fitting a species arrogant enough to call itself Homo sapiens onto a planet with a biosphere as a design challenge. He said we needed a form of ecological design to address it. This Homo economicus you described, blindly consuming everything in its path, is a maladaptive pattern that seems almost cancerous to the living system.

But if we remember that our core pattern as a species has been bioregionally regenerative for most of our evolution, we can see that this maladaptive pattern has lasted only about 5,000 to 10,000 years. I would go as far as saying bioregioning is our species’ evolutionary survival pattern. None of us would be here if we hadn’t been regenerative expressions of place—or, scientifically speaking, a keystone species that co-created the ecosystems in which we dwelt. Evidence from around the world—North America, South America, Europe, Africa—shows that so-called pristine rainforests were not untouched by humans but gardened by them to be as abundant as they are now. Dr. Lila June’s work, Architects of Abundance, details this for North America extensively.

So yes, your conjecture is absolutely right. Bioregioning is essential to refitting humanity into a planet with a biosphere and regenerative patterns that sustain life.

Nate: I could do the thought experiment in the other direction too. After the carbon pulse, hundreds or thousands of years from now, humans—our descendants, however many there will be—will almost by definition be living bioregionally.

Daniel: Yes, absolutely.

Nate: Trick question, Daniel. If and when we colonize Mars, would people there be living bioregionally?

Samantha Power: I can respond to that if that’s okay with you, Daniel. Bioregionalism, for me, is a way of organizing ourselves, governing ourselves, and telling stories about ourselves that is rooted in living systems, patterns, and principles. Because life on Earth did not evolve on Mars, I think it would be very difficult for us to live bioregionally there. It would be missing the living part.

Samantha Power: I can respond to that if that’s okay with you, Daniel. Bioregionalism, for me, is a way of organizing ourselves, governing ourselves, and telling stories about ourselves that is rooted in living systems, patterns, and principles. Because life on Earth did not evolve on Mars, I think it would be very difficult for us to live bioregionally there. It would be missing the living part.

Nate Hagens: Yes, that’s the point, it would be missing the living part.

Samantha: The Earth is part of our body. Humans are an extension of the Earth. We were born out of the web of life on Earth, and bioregionalism is about coming back into a deeper recognition of that truth and living in harmony and reciprocity with all the plants, animals, insects, water, and rocks in the places where we live. That is our task as humans on this planet: stewarding those relationships. If you take us and put us on Mars, it’s not going to work in quite the same way.

Nate: So again, that’s one of the juxtapositions of technology—putting things into buckets versus ecology and systems. How important are indigenous cultures and ways of living in contributing to bioregioning and bioregionalism?

Samantha: Certainly, indigenous wisdom, ways of seeing, being, and governing are some of the best information we have about how to live bioregionally, how to live in a way rooted in living systems, patterns, and principles. That’s why there’s such a resurgence of interest in indigenous ways of relating to the natural world, structuring economies, and creating governance systems right now—because we see that they’ve been holding onto intelligences that so much of modernity has forgotten.

Nate: Is it fair to say that indigenous cultures extant today have been living in a bioregional way, but their regions have been shrinking due to external forces?

Isabel: Bioregioning, which we haven’t fully explored yet, is a practice of relationality. Indigenous people live in relation to place. It’s a two-way exchange between place and people, and in many ways, that’s what bioregioning is trying to get back to. It’s about this sense of belonging to a place and having an identity rooted in place. We’ve lost so much of that.

Nate: Here’s a question: Does one have to understand bioregioning to live bioregionally? Or can you just be human, follow your natural instincts, and live that way? How do you parse that?

Nate: Here’s a question: Does one have to understand bioregioning to live bioregionally? Or can you just be human, follow your natural instincts, and live that way? How do you parse that?

Samantha: I’ve had indigenous colleagues say that bioregioning is just a word white folks came up with for what they’ve always been doing, for how they’re already living. Likewise, loggers in the Sierras and many others are bioregioning without being steeped in the philosophy, nor do they need to be, because they’ve never stopped living that way.

Daniel: It’s important to understand that both regenerative cultures and bioregioning aren’t some new fringe proposition we need to consider. They’re life’s pattern—they’re happening whether we want them to or not because that’s how life organizes. Every act of caring, sharing, nurturing, protecting, and loving that connects people to community and place is bioregioning.

It’s much more about fanning the embers of what is already there behind the story that separates us from nature. That’s why the link to indigenous cultures matters—because it doesn’t serve to separate humanity into indigenous and non-indigenous categories. We all need to come back home to place and to the living fabric of life. Then, we’ll all be indigenous again. We are born into life as life.

Nate: So how do you define a bioregion? Both its definition and, practically, in terms of an actual place? I live on the border of Wisconsin and Minnesota, and I’ve never thought about what the bioregion here might be.

Isabel: Here in South Devon, we’ve defined ourselves by water. Bioregions are defined by geology and geography, but it’s also a felt sense. This is not a purely scientific process. It’s very much about whether you feel at home. People who live in South Devon instantly know when they’re crossing into Cornwall or moving over Dartmoor into North Devon. You just know you’re not in your home place anymore. Your home place can be very big, like Cascadia, or smaller, like South Devon, which you can cross by car in about two hours.

Nate: Are there concentric circles of what might be defined as bioregions? I know the 20-minute bike ride from my house has a distinct feel, but then there’s the three-hour drive—a broader sense of the Upper Midwest. Where do you draw the boundaries? Are there strong, semi-strong, and weak forms of bioregional boundaries?

Daniel: I found it helpful in a conversation with Tyson Yunkaporta about the natural bioregional boundaries in Australia between tribes. When we talk about boundaries, we need to adopt an indigenous understanding of them. Tyson said a boundary is a place of kin-making, not kin-breaking. It’s about relationship-making. It allows you to say, “This is where we are, and there’s a beyond,” but the idea is to connect and interweave dynamically with that beyond—not to build a wall and shut it out. So, when engaging with bioregioning, there are two terrains to consider: one is the biogeophysical terrain—the topography, river systems, soil, fauna, and flora—and the other is the terrain of consciousness.

That’s what you were referring to, Nate, with your sense of crossing a bridge, going through a tunnel, or climbing a ridge and feeling, “I’m out of my home place now.”

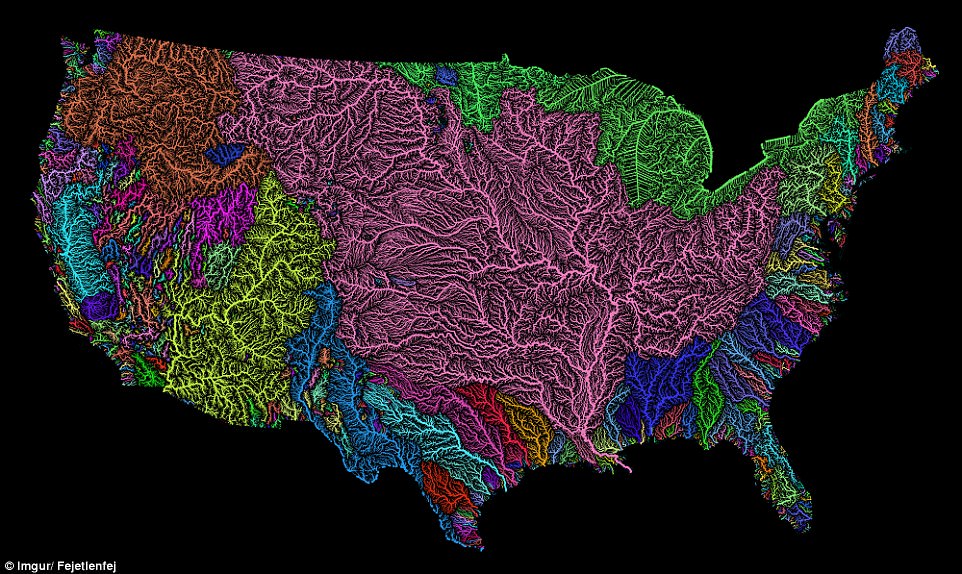

Samantha: At the BioPhi Project, we talk about drawing bioregional boundaries in terms of hard lines, soft lines, and human lines. Geological, ecological, and cultural lines are all important in mapping a bioregion. Life is organized fractally, and bioregions are as well. Some bioregions work at a small watershed scale but see themselves nested within a larger watershed and within Salmon Nation—a bioregion spanning the Pacific coast, encompassing everywhere salmon exist along that coast. Designing economics and governance informed by these fractals is a vital part of bioregioning.

Nate: Back when we were the original hominids in Tanzania, on the plains near Olduvai Gorge, it was just one bioregion. Then we expanded around the world. How much of bioregioning—both the geographic boundaries and the conscious boundaries—runs up against population constraints? For example, if there’s a place that is overpopulated, do people claim it as their “new bioregion”? How much is a bioregion implied by its own carrying capacity?

Samantha: Carrying capacity is not fixed. These places evolved as humans moved into them, stewarded them, and, in many cases, brought more life to them. Over longer geological timescales, carrying capacities have shifted based on how well humans cared for those places. The regenerative potential of life tells us we can change the carrying capacity of places, even today, and sometimes in relatively short periods.

Nate: I just had an insight. The existence of hydrocarbons has essentially moved our bioregions underground. It disrupted the natural ecological flows and recalibrated the entire calculus.

Daniel: There was a bifurcation point in human history. We had the choice, as we evolved, to either increase the carrying capacity of the land by terracing, caring, foresting, and building more complex forms of agriculture—or to take the power-over route. That led to city-states, nation-states, annexing other lands, and essentially running a path of extraction. We chose the latter.

Nate: Or, rather, a faction of “we” made that choice, and because of that, they amassed power, resources, and military strength.

Daniel: Exactly. And if we frame it in terms of ecological and evolutionary biology, 5,000 to 10,000 years is about the maximum time a maladaptive species pattern can persist before evolutionary kickback begins. That’s what we’re seeing now. Industrial civilization—Elon Musk’s vision of Mars colonization—is an extreme manifestation of this maladaptive pattern. The idea of going off-planet is the ultimate perversion of the power-over story. We’re becoming the locusts of the known universe, burning this planet as we search for the next one to burn. The challenge now is to return to our species’ survival pattern.

Isabel: The hinge point for this maladaptive pattern lies between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods—the shift from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agriculture. That change set us on a different trajectory. But we’ve been making decisions for centuries, if not millennia, without fully understanding their long-term consequences. It’s hard to pinpoint blame on one moment.

Nate: In hunter-gatherer times, was there a recognition of, “This is not my bioregion; this is someone else’s”?

Isabel: If you go back to Neanderthal times, which I know most about because I was an archaeologist, there’s evidence they worked with geosystems and earth systems. For example, the site I excavated in Jersey, which was used for butchering big game like woolly mammoths, was active for 250,000 years. That’s an extraordinarily long time. The people using that site moved south when the ice came and returned north when it retreated. They lived in harmony with the earth systems of the time and adapted to those changes. Today, it’s much harder for us to move and shift our locations in response to environmental changes.

Were they traveling from bioregion to bioregion? Yes. They had to know how the game functioned in each region, where the water was, and what life would be like along the way. For me, this all comes back to adaptation. How adaptable are we, for both good and ill?

Nate: Quick side tangent: What’s the coolest thing you ever found in your field studies as an archaeologist?

Isabel: I found a woolly mammoth tusk.

Nate: That would be cool. It must bring you emotionally back to when that animal was alive, even just for a brief moment.

Isabel Calisle: It really does.

Nate: How can bioregioning, as we’ve been discussing, be used to address the ecological, social, and economic challenges humanity faces?

Isabel: In South Devon, we’re pursuing an experiment in bioregioning. For me, bioregioning relates to the commons and commoning. Commons are only kept alive by the people who care for them—those who are “commoning.” Similarly, bioregions only come alive because of people functioning in a bioregional way.

Nate: Can we even have bioregioning without a commons? Is a commons a necessary precursor?

Isabel: That’s a very good discussion, which we should get into shortly.

What we’re doing here in South Devon involves many entry points into bioregioning. You can approach it through green manufacturing, regenerative agriculture, or democratic processes, like those Eleanor Ostrom explored in her work on governing the commons. The key question is: how do we reimagine citizenship? Unless people are given the opportunity to reclaim their agency and take responsibility for how they live in their places, I don’t think we’ll make it through.

Nate: So in many ways, bioregioning is the antidote to the economic superorganism, which has taken away our agency—or at least, we perceive it has. Daniel, how would you answer the question of how bioregioning can solve some of our meta-crisis issues?

Daniel: It’s interesting to think about the potential of coming home to place, rather than losing ourselves in the meta-crisis of trying to solve problems at a global scale. That’s what we’ve failed to do for the last 50 or 60 years. We still have international conferences that try to address problems by making them more abstract and scaling up solutions, but the bioregioning proposition is the exact opposite.

It says: What if all the facets of what we now call the world’s problems or the polycrisis show up in your bioregion? They show up with names, faces, specific ecosystems, histories, and timelines. Suddenly, by becoming specific, detailed, nuanced, and alive, these “problems” transform into potential. They become the living potential of life coming through us, expressing itself as bioregional custodianship.

In the context of the polycrisis—where systems are already collapsing—bioregioning is also a community resilience-building strategy. It may be the only way our species can pass through the eye of the needle in the coming decades. If we use our time wisely to build resilience infrastructures at local and bioregional scales, we may adapt to uncertain times. Otherwise, we risk descending into more wars over resources. Bioregioning isn’t just a proposition—it’s a pathway through the eye of the needle, if we’re lucky. Most likely, though, it won’t work for everyone.

Samantha: I’ve spent the past 10 years thinking about how to shift the economic superorganism to redirect money toward supporting life and people’s well-being, instead of perpetuating the extractive, destructive economy that’s turning the Earth into capital. I’ve tried to approach this top-down, with research and logic, but I’ve seen the limits of that approach in changing the actions of those who hold power. Eventually, I came to bioregionalism because I wanted to get closer to what’s real.

The most urgent work now is the stewardship and regeneration of our lands, waters, and cultures in ways that are truly regenerative and connected to life. Bioregionalism invites us back into being good citizens of the places we live. In the United States especially, there’s a sense of hopelessness around what can be accomplished at the national level. While that is something to grieve, it’s also an opportunity to explore decentralized governance and economic structures that offer more agency, responsibility, and sovereignty, while aligning with the flows of life.

Before the United States existed, a tapestry of Native nations covered this land. Now is the time to rebuild nature states and create decentralized, ecologically informed governance structures.

Daniel: Here’s a bit of history I learned recently. In 1879, John Wesley Powell, who later became the director of the U.S. Geological Survey, suggested that America should be organized by watershed boundaries. There’s even a map showing the entire United States divided into watersheds. That was a real missed opportunity. Perhaps, as the U.S. government faces existential crises, coming back to more nuanced, place-rooted administrative boundaries could be an opportunity.

Nate: That gets into some thorny questions. There are different timelines: triage, transition, and the longer term. I’m convinced that in the long term, humanity will have to live bioregionally. But in the short term, if we were to change boundaries to create nature states while the United States as a centralized power still exists, is bioregioning a threat to centralized power? Or is it small enough that it can coexist?

Samantha: My favorite permaculture principle is “It depends.” It depends on who you’re talking to within those governments and systems, their worldview, and their objectives. There’s more conversation emerging—just in the past six months—around bioregionalism within the United Nations. Historically, the UN has been driven by nation-states, but people within that organization are starting to see the limits of what the nation-state paradigm can accomplish when addressing large-scale ecological regeneration, climate change, and other global challenges.

For example, in the U.S., the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act has allocated massive resources to communities for climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. However, if communities aren’t organized to apply for and govern those funds, the money won’t make a meaningful impact. So, even at the multilateral and nation-state levels, there’s a recognition that this work must be decentralized. There’s interest in flowing resources toward bioregional organizing teams that bring people together in their landscapes and watersheds to decide on the most important projects to fund and implement.

Nate: Could you briefly follow that up with a couple, three brief examples of what such projects might look like?

Samantha: Sure. So the BioPhi project is working with around 15 different bioregional organizing teams across North America, Central America, and South America. And these vary in scale, going back to our conversation earlier about how you map a bioregion and what the boundaries are. But one of those teams, (ReVillage Green Valley), is based in West Sonoma County, so not far from where I live in the Bay Area.

And they are starting very small with a town that has been kind of neglected for a while. There are a lot of empty buildings in this town. There was a blighted lot, and they invested in creating a town square. In the center of the town square, there is a museum for the future, which is essentially a shipping container where people are going and sharing their ideas for the future of that town and the whole watershed surrounding it. What would ecological and cultural regeneration in that place look like? What types of gatherings would they like to have? What types of indoor common spaces? How could salmon be brought back to that creek?

So that’s one example.

Another example is our mutual friend Atossa Soltani and her colleagues at the Amazon Sacred Headwaters Alliance. They have a huge bioregional plan for regenerating this massive area that is the headwaters of the Amazon River. They’ve been working with indigenous nations across Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia to co-create a regenerative vision and plan for that entire region, including the land, waters, and biodiversity. That organizing work is incredibly valuable for any entity that cares about the protection of the Amazon. We’re working with them to figure out what capital sources can fund that stewardship and regeneration, including multilateral or bilateral donors.

Isabel: I wanted to chime in and say that bioregional practice, I think, has a very important role to play in depoliticizing what we’re seeing happening right now. It depoliticizes climate change, it depoliticizes the injustices of inequity, it depoliticizes all sorts of things because it brings us back to a level of practice and connecting. And this is very much a practice, not a theory, which kind of gets underneath all these dualistic ways of thinking—right or wrong, left or right, whatever. But it takes us into a different space, and I think that’s incredibly important.

I also see the capacity of bioregions and bioregioning to step in where governments can’t function in a joined-up way. For example, in the UK, central government at Westminster is responsible for things like defense. Then you have county councils, which cover fairly large regions, responsible for education and transport. Then you have regional authorities responsible for roads and waste collection. And finally, you have parish councils. But they’re all working in silos. None of them are thinking in a joined-up way. And we need to start thinking in a joined-up way, having joined-up strategies.

Nate: So, in a way, bioregioning—the verb, the activity—is post-partisan.

Isabel: Yes. Yes, that’s a good way of talking about it. Absolutely.

Daniel: With regard to the European situation and whether it’s a challenge to the political superstructure: the European constitution enshrines the political ideal of subsidiarity. It’s the concept of how we want to be governed in Europe. The reality in Brussels and most nation-states within Europe is different, but in theory, national governments and the European government are subsidiary to, and in support of, the local and regional decision-making processes of people in the places where they are affected by those decisions.

And so, it’s actually, in many ways, an opportunity to implement what has already been professed—that we do need to devolve governance in such a way that people have more say over how the money is spent. Participatory budgeting and those kinds of things are being experimented with.

Just to give you a few examples: in Holland, for the last 12 years, an organization called CommonLand has been focusing on ecosystem restoration, but it does so in a regionally bound way. Their approach involves first building a multi-stakeholder network in a particular region of landowners, local governments, and businesses. Then they start working with them on a 25-year plan for landscape-scale ecosystem restoration.

They’ve been working in a number of places for over a decade now. There’s a project in southern Spain near Murcia where a million hectares have been pulled together into a regional transformation project. These were areas that otherwise would have desertified, where people were fleeing villages. In many cases, bioregioning is a response that enables public-private partnerships at the local level to solve problems that national governments have not been able to address. It’s not a challenge; it’s a support strategy, particularly as we face the realities of failing states.

Nate: Could you define or alter the definition of bioregioning as simply applying permaculture principles to the scale of watersheds and regional ecosystems?

Samantha: I just spent 10 days in a permaculture course up in West Sonoma County last month, Nate, where I was asking this exact question. I was particularly looking at permaculture principles, rainwater harvesting principles, and Fritjof Capra’s living systems principles, and how they inform the design of financial institutions and economies that are aligned with bioregionalism and support the transition to regenerative bioregional economies.

So yes, in the case of designing a bounded financial institution or an economic transition strategy, I believe they can be applied. But I’ll let Daniel answer in terms of the broader bioregionalism perspective.

Daniel: I would frame it slightly differently because, in many ways, permaculture is a Western abstraction of indigenous land management and relational patterns that are ancient. They respond to our species’ core pattern of regenerative bioregioning. If permaculture is codified in a language that we understand, it certainly helps us apply bioregioning at a regional scale.

Nate: My insight is that instead of me and my neighbor each applying some permaculture principles borrowed from indigenous wisdom, we’re all part of a watershed. There’s a logic to 10,000 people in this area doing similar things, based on shared factors like the soil, wind, seasons, and bluffs.

Samantha: One thing I’d like to add, Nate: I gave a very positive answer earlier about how these entities—bioregional organizing teams—are needed to achieve objectives and mandates, and to avert existential risks. But at the same time, it’s explicitly one of our objectives in building these bioregional economies to build power in grassroots and indigenous communities. That can be very threatening to the existing paradigm.

Something I’ve been discussing with our friends at the Civilization Research Institute is how we build a protective membrane around these emerging, very nascent bioregional economies. This would allow them to develop something rooted in living systems principles within the broader monoculture capitalist economy that often wants to squash them.

Nate: About half of what I know about bioregioning I’ve learned in the last 45 minutes, so I’m really just a student of it. When I think of bioregionalism, I think of watersheds, ecology, and systems. But what I’m hearing from you all—especially you, Samantha—is that bioregioning is really a merger of ecology and watersheds with some form of decentralized governance apparatus. It’s not just ecology. There’s got to be governance embedded in there, right?

Samantha: There has to be power.

Daniel: Just to add, as this is Bioregioning 101, it’s helpful to bring in historical context. People like Peter Kropotkin and Patrick Geddes, over 100 years ago, proposed regional-scale organizing as a solution. So, this movement has always included social, political, and economic dimensions. It’s not just an ecological proposition; it’s where all of these elements come together at a scale that makes sense for human settlements.

Nate: But if people agree with bioregioning as the future, doesn’t it imply that some areas are much more suitable than others? For example, Cascadia is a desirable destination with its watersheds and rainfall, while Phoenix, Arizona, is way out of line with its carrying capacity. Wouldn’t the discussions around bioregioning in these places look very different?

Daniel: There’s a worldview dimension to all of this, which brings us back to the question of indigeneity. At the point of bifurcation between carrying capacity and population growth, if people believe they are part of life—that life is kin—then they understand that what they do to the tree of life, they ultimately do to themselves. That worldview introduces checks and balances when it comes to expanding into or exploiting another bioregion. It stops us from becoming what I called the locusts of the known universe.

Of course, human history has always had conflicts, but when rooted in a worldview of kinship with life, competition within the human species is tempered by the need to maintain the overall living system. That’s where we lost our way—when we labeled cultures as primitive, despite their core survival patterns being in right relationship with the planet and each other.

Isabel: This brings us to the question of how we actually do this. How do we get back into a right relationship with the land? How do we imagine bioregional governance? What would a bioregional economy look like? There’s no doubt in my mind that climate change and the imperative for climate adaptation give us an opportunity to organize ourselves bioregionally.

Human organizing functions very well at the scale of a bioregion. When we ran a series of bioregional conversations back in the spring and summer, guests from South America immediately identified that their political organizing was happening at the scale of the bioregion. That’s how they relate to their bioregions.

So, how do we actually do this? In South Devon, we’re experimenting with working alongside our regional council. We’re not setting up something to take over from it, but we are saying we need an entity that sits outside the council—one that is not aligned with party politics but is empowered to make decisions about projects that need investment in the bioregion.

We’re doing this in a strategic way, looking at how investments in community energy projects relate to water quality, which connects to farming, transport, and livelihoods. It’s about always looking at the whole picture.

Nate: That actually sounds like a wonderful idea. Current politics make it difficult for governments to integrate these concepts, but if there were a “shadow council” in each watershed—without political authority but with the capacity to convene, scenario plan, and identify investment needs for their bioregion—that could report to the official council quarterly, what’s stopping that from happening everywhere right now?

Isabel: Absolutely, and that relates to what Samantha is doing. It requires financing, and it must come from multiple sources to maintain independence. It can’t rely solely on government, philanthropy, or community funding. It needs a diverse set of funding streams.

Nate: So, is bioregioning inherently dependent on philanthropy or government funding, or can it be for-profit?

Daniel: To some extent, we need to redefine what “profit” means. Is it profit for the financial system, or is it regenerative for the future?

Nate: So, you’re saying profit could be reframed as ecological or social returns?

Daniel: Exactly. Again, I have the audacity of saying neither regenerative cultures nor bioregional regeneration nor regenerative economics is anything new and that in every place and in every bioregion, there are mothers and sons and daughters and fathers caring for children and for elderly, and in ways that are not part of the current economic system.

That is the living, caring, bioregionally active, regenerative economy that is already in place. And, in re -our patterns of production and consumption, creating economic opportunities at the regional scale, at that watershed scale, to meet the human, basic human needs within the region from regeneratively grown resources in the region.

We make the economic activity of the local economy and regional economy a driver of ecosystems restoration, of healing our ecosystems and our watersheds. And that’s really the massive opportunity here, in a, time of increasingly volatile global economic systems and supply line disruptions, we are building a scale linked and place routed economy again.

Nate: Isn’t another word for bioregioning, um, Reality? I mean, it seems like this is just another shift in our perception. Like the listeners and watchers of this program, they could, after this episode is over, walk outside and declare that they themselves are bioregionalist and just shift their perception, start to do things more locally in the direction of the things the three of you have been discussing.

Samantha: Absolutely. The current economic system and centralized governance structures are incredibly brittle. Bioregional governance and economies will be more resilient as the old systems become less relevant over time. These models align resources, energy flows, and decision-making with the needs of place.

Nate: So, what are some things that individuals or communities could start doing now to begin moving toward this bioregional future? What are the first steps?

Daniel: Earlier, we touched on the idea that bioregioning is not a new concept but a return to life’s patterns. I’d like to share a poem by Gary Snyder called For the Children, which encapsulates the essence of bioregioning beautifully:

The rising hills, the slopes of statistics

lie before us.

The steep climb

of everything going up, up,

as we all go down.

In the next century

or the one beyond that,

they say,

are valleys, pastures;

we can meet there in peace,

if we make it.

To climb these coming crests,

one word to you, to you and your children:

Stay together

Learn the flowers

Go light.

This captures the idea of staying connected, paying attention to the specifics of place, and treading lightly as we move into uncertain times.

Isabel: I’m going to give a different answer. Someone recently asked me how they could start bioregioning in the south of England. I suggested looking into climate adaptation as a gateway. For example, find out what your local council is doing regarding climate adaptation strategies. They likely don’t have a strategic plan. But by engaging with local entities that hold decision-making power, you can begin joining the dots within your bioregion.

It’s about identifying opportunities to connect initiatives—whether it’s in community energy, regenerative agriculture, or water management—and offering solutions that work holistically across these systems.

Samantha: For those who are interested in bioregional finance and economics, I’d point to resources like the BioFi Community of Practice. It’s a global group of over 400 people exploring bioregional financing strategies on a platform called Hilo. There’s even a map function where you can see who in your area is working on bioregional projects. It’s a way to connect with others and start building plans for your specific bioregion.

I’d also highlight Inheritance Day—a holiday created by some friends of mine where we envision a world 150 years into the future, where humans are living in harmony with the Earth. It’s an opportunity to reflect on the steps we need to take to achieve that vision. While the official date is December 12th, anyone can celebrate it at any time. Host an Inheritance Day gathering and imagine what sacred reciprocity with life could look like in your bioregion.

Nate: That’s fascinating. I recently had a podcast with Bill Plotkin, who talked about ecological adulthood—what it means to become an adult in a way that aligns with the larger web of life. That dovetails with what you’re saying: taking responsibility for our bioregion and realizing that no national government is going to come and fix it for us. The work begins in our own communities, and the mindset shift is essential.

So, what would success look like for bioregioning in the next decade? What are the guideposts we might look for to know it’s working?

Isabel: One clear sign would be the widespread adoption of regenerative agriculture—farming practices that prioritize soil and water health. Another would be a shift in governance, with decision-making devolved from centralized governments to local or regional levels. We’d also see the rise of citizen-led research and knowledge-sharing networks, enabling people to monitor changes in their bioregion and make informed decisions.

Funding would be another indicator. If more resources flow into systemic, joined-up initiatives—like community energy projects that link to water quality, farming, and biodiversity—it would show that bioregional thinking is taking root.

Samantha: I’d add the emergence of place-based, regenerative, and resilient economies. These economies would be more connected to the geologies, ecologies, and cultures of their bioregions. They’d operate within the regenerative capacities of their environments, creating healthier food, water, and people, along with a greater sense of belonging.

We also need to redefine value. Right now, value is largely determined by global capitalist systems, which prioritize quantification and financial returns. In a bioregional economy, value would be relational—flowing between people, bioregions, and the more-than-human world. This shift in how we perceive value would be a major milestone.

Daniel: In the near term, we’d see a relocalization of food systems. Communities would reconnect with local farmers and producers, fostering healthier ecosystems through regenerative practices like agroforestry. Landscape management would become a collective effort, addressing issues like wildfire prevention, flood control, and biodiversity restoration.

In Catalonia, for example, there’s a model of voluntary credits for ecosystem restoration. It’s not just about carbon sequestration but includes water retention, biodiversity, and social outcomes. Initiatives like this provide a template for linking regional businesses and governments to the health of their bioregion.

Nate: So, areas that adopt bioregioning practices will likely be more resilient to the disruptions ahead?

Samantha: Absolutely. The dominant economic and governance systems are brittle and unprepared for the cascading crises we face. Bioregional approaches are inherently more adaptable and aligned with life’s regenerative patterns. They offer a way to build resilience and navigate the challenges ahead.