Inner Dimensions of Systems Transformation

Featured image | Photo by Jr Korpa

Background

This article is based on selected content from a Deep-Dive paper which itself complements Earth for All: A Survival Guide for Humanity, a Report to The Club of Rome by highlighting the overlooked inner dimension of system change, and supplying systems thinkers with the language to advocate for psychological, social and spiritual factors crucial to sustainable solutions. It discusses worldviews, mindsets, values and identity as root drivers of cultural behaviour, their interaction with psychological and behavioural tendencies, and the transformative inner capacities that can be cultivated to intervene at deep leverage points; and introduces existing initiatives leading the way in integrating inner and outer dimensions of system change.

The full paper and all original citations can be accessed here.

We belong to each other; we cannot cut reality into pieces… Every side is ‘our side. – Thich Nhat Hanh

Implicit in the operation of values, identity is another key aspect of mindset—a collection of perceptions and stories about what it means to be ‘me’ or ‘us.’ These may concern our personalities and bodies, encompass groups such as family, tribe, race, or nation, or even all of life. Different structures of identity predict individuals’ sustainable attitudes and can produce significant differences in collective behavior. Historically, for example, in a period when China identified with an interdependent, “harmonic web of life” and deployed its immense navy with restraint, a European imperative to dominate and exploit the world was strongly influenced by a biblical notion of human power over a hostile natural world, resurgent in Enlightenment thought. Over centuries, this separatist concept of identity helped shape today’s globalized modern society, underwriting its deepest inequalities and cementing the difficulties we now face in fairly addressing the consequences.

The boundaries of group identity are fluid. Indeed, throughout human history, the ‘circle of empathy’—the group of other beings to whom we typically extend care—has expanded as a condition of survival. However, from the systemic exploitation of nature to the dehumanization of others and the polarization that corrodes essential social trust, barriers to Earth for All’s extraordinary turnarounds remain rooted in stories of separateness. To collectively choose radical solutions on behalf of the whole requires not only “the broadest coalition the world has ever seen” but a deeper story of humanity as identical with all of life.

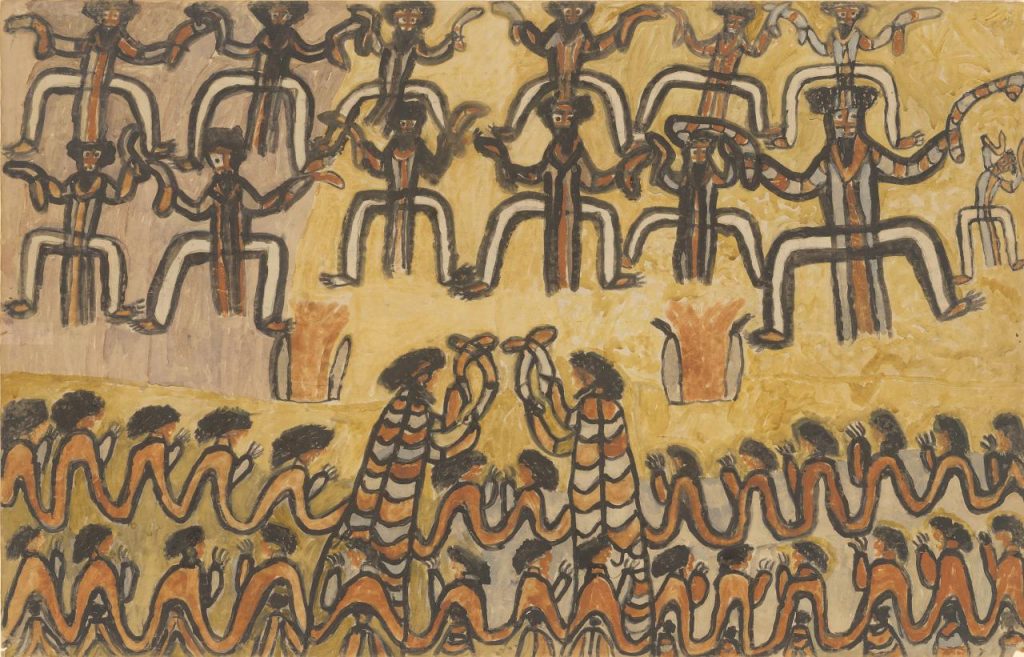

The story we require is anything but ‘new’: societies rethinking separateness in the face of crisis have much to learn from cultures that more readily perceive identity beyond the individual. African Ubuntu philosophy, for example, identifies humanity as fundamentally relational and morally obligated towards past, present, and future generations. Indigenous wisdoms are typically founded upon identity that is relationship-based and nature-connected, compelling earnest consultation in consideration of system change. In addition to relationality, core values in ‘4R’ or ‘5R’ frameworks of Indigenous worldviews and pedagogy include reverence, respect, reciprocity, responsibility, and redistribution. These are considered “sciences and technologies… developed since time immemorial by communal relations between human and non-human beings.”

Contributors

Jamie Bristow Public Narrative and Policy Development Lead for the Inner Development Goals; Research Fellow at Life Itself Institute; Honorary Associate of Bangor University

Rosie Bell Senior creative associate at Life Itself Institute and the Climate Majority Project

Christine Wamsler Professor of Sustainability Science at Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), Founder of the Contemplative Sustainable Futures Program

Tomas Björkman Founder of the Ekskäret Foundation and member of The Club of Rome

Phoebe Tickell Founder and CEO of Moral Imaginations

Julia Kim Program Director, Gross National Happiness Centre, Bhutan and member of The Club of Rome

Otto Scharmer Senior lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, founding chair of the Presencing Institute and member of The Club of Rome

This is not to imply that humanity’s ‘authentic’ state is straightforward nature-connectedness. Since our earliest history, humans have tended to overstep environmental boundaries, and ecological thought within Indigenous societies represents hard-won lessons in sustainability. In the current era, however, widespread disidentification with nature contributes to a vicious circle with distracting technology and environmental degradation.

In this context, practices of nature connection and those that cultivate ‘self-expanding emotions’ such as gratitude, awe, and compassion can broaden the sense of identity beyond a narrowly constructed ‘self’ and strengthen connection to the world we belong to. Connection practices may prove key to climate action: in one study, individuals with high nature-connectedness were found to be roughly twice as likely to exhibit pro-environmental and conservation behaviors. (See section 2.6 on embodying connection).

Religion, Spiritual Sensibility, and Existential Inquiry

“If we each offer the best of our respective traditions, we may yet see a way through our difficulties.” – Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change

Religion remains a primary unifying force in collective identities across the world. Despite the rise of secular individualism, 85% of people globally still identify with a religion. Throughout history, shared belief has enabled collectivism at increasing scales, supplying communities with meaning, cohesion, and a sense of both the inner and the self-transcendent not easily replicated outside its container of shared narrative, worldview, and ritual. Without denying the complex role of religion in warfare and violence, and even the contribution of certain beliefs and practices to the environmental crisis, we may inquire into the role such a powerful inner dynamic has to play in supporting prosocial, pro-environmental behavior change.

Organized religions today convene powerful networks of communities; and their leaders occupy influential platforms at deep systemic leverage points. Many major religions hold life to be inherently sacred. Accordingly, some leaders are already working to influence their communities’ response to global crises; emphasizing obligations of planetary stewardship within the eternal ethical frameworks of their own faith – Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudate Deum and the recent Al Mizan Islamic initiative among prominent examples.

Beyond specific religions, many operate worldviews influenced by spiritual sensibility. For example, as many as one in three people in Europe and the USA may identify as “spiritual, but not religious.” Even without religious convention and structure, sincere spiritual inquiry, practice and experience can “help us get things in perspective in the fullest and broadest and deepest sense.” Achieving the extraordinary turnarounds will depend upon a measure of soul-searching across society – and a sense of the sacred, whatever shape it takes, is profoundly relevant to sustainability challenges.

Global crises raise existential questions – individual and collective. Why do we exist? What’s my relationship to the world that will persist beyond my lifetime? What are my responsibilities towards the collective? Religious frameworks and spiritual inquiry tend to support people in exploring such questions. In secular contexts, there is a growing need to develop a similar capacity.

To choose, design, and enact effective, collective solutions at the scale and complexity called for by Earth for All requires not only interrogation of the mindsets that shaped our predicament, but also understanding of our innate, often latent capacity to transform them.

Liberating Attention; Reclaiming Agency

Tell me what you pay attention to and I will tell you who you are. – José Ortega y Gasset

Attention is the inner faculty that binds all others together into conscious experience – and it is foundational to action at all scales. To choose effective action, we need awareness of what’s happening. Furthermore, what we collectively pay attention to determines what we consider important and worthy of resource and energy. But whereas we may think that we’re in charge of what we pay attention to, evolutionary drives combine with market forces to ensure otherwise. Humans are pre-programmed to prioritize survival objectives in our evolutionary landscape. Despite our aspirational ‘higher’ values, primal impulses – attuned to acquire what tastes good, to avoid immediate threat, to seek group safety and to reproduce – regularly snatch attention from our chosen object of focus. Likewise, while globalized modern society is built on a model of humans as rational agents, acting out of choice, neuro and cognitive science show that involuntary impulses, entrenched habits, and ‘autopilot’ are often directing behavior.

With the help of smartphone technology, global economic and political powers have learned to ‘hack’ these neurophysiological systems. Their power to capture attention and to sell it now directly affects over half of the global population.

Consequently, at a time when we most need to concentrate on our shared world and its needs, our attention has never been more distracted and fragmented. As well as directly limiting our agency for system change, corrosive impacts extend to our mental health, cognitive capacity, relationships, social trust, and nature-connectedness. The same media algorithms that drive unsustainable consumption are exploited to manipulate political behavior, seed disinformation, and entrench polarization across the world. The importance to society of reclaiming agency in the sphere of attention cannot be overstated.

Adequate policy interventions are long overdue that can regulate the attention economy’s monopoly of our focus – for example, the regulation of social media offerings to limit attentional hijack, or replication of French workers’ “right to disconnect”. While we work collectively towards these, we may also purposefully increase our own capacity to resist digital manipulation. For example, our innate capacity for mindfulness—a particular kind of attention—can be cultivated through practices that protect against proactively distracting stimuli and enhance self-control and presence.

Overcoming Bias and Seeing Clearly

We see the world as ‘we’ are, not as ‘it’ is; because it is the ‘I’ behind the ‘eye’ that does the seeing. – Anais Nin

Commonly we assume that beliefs and choices are based on information about what’s really happening in the world, gathered by the senses. But cognitive science shows that, usually, we see the world we expect to see; quickly classifying new experience according to existing models. These short-cuts are fundamental to coherent understanding and decision-making amid chaotic sensory stimuli. However, they also contribute to ‘confirmation bias’, limiting our receptivity to novel information and possibility. At a societal level, bias towards existing beliefs and judgments reduces our capacity to respond skillfully to a changing world – contributing, for example, to a 50-year delay in meaningful action on climate science.

Susceptibility to confirmation bias can be increased by experiences of worry or perceived threat, or the cognitive dissonance that arises when new evidence reveals misalignment between our behavior and our values. Thus, widespread climate denial is not simply a meme propagated by vested interests – it’s a normal, protective mechanism that involves avoiding or minimizing uncomfortable truths in favor of less challenging narratives. Climate disavowal, a form of ‘soft denial’ that admits the facts but plays down the threat, similarly distorts perceptions to limit discomfort – and may now be more common than outright denial.

In the context of collective action at all levels of society, positive feelings like hope play a vital role in overcoming resistance to uncomfortable truths, limiting ‘doomerism’, expanding possibility, and sustaining effort. However, willful optimism about chances of success can itself become a form of soft denial and can perpetuate complacency or misdirected efforts. To initiate the extraordinary turnarounds calls for acceptance of the real extent of crises, including possible limits to ‘fixing’ them. Effective strategies can only be based on a clear-eyed assessment of a situation, and leaders have a role in balancing appropriate hope and realism in public communication; combining motivation with attunement to the depth of the crisis.

Biases and defense mechanisms present powerful psychological barriers to collective action and political will for systems change; polarizing debate and hindering consensus-building. Meta-cognition, self-awareness, and education around these common mechanisms can reduce their undermining influence on critical thinking and decision-making. Interventions have been developed specifically to help civil servants manage complex decision-making by combining awareness-based practices with inquiry into the predictable distortion of thinking by emotions and biases. In the US, pioneering mindfulness- and compassion-based ‘ColorInsight’ practices support developing awareness of racial bias; in service of effective collaboration towards social change.

Developing Sense-Making and Grasping Complexity

No man was ever wise by chance. – Seneca

The escalating complexity of human systems is outstripping our capacity to manage them – even while our power to cause catastrophic harm accelerates. The interconnected crises of sustainability and inequality emphasized in Earth for All are characterized by ‘adaptive’ problems: they cannot adequately be addressed with current knowledge and skills. Rather, they demand that we learn—or unlearn—and grow.

At both individual and societal levels, it’s possible to develop the cognitive, emotional, and relational capacities to better comprehend and navigate complexity. Wisdom traditions have long advocated the societal benefits of cultivating heart and mind, and contemporary research is beginning to catch up. Science shows that adults develop psychologically throughout life, that practice can dramatically alter brain structure and activity, and that inner development programs for individuals and teams can have profound positive effects on inner capacities.

Trainable cognitive capacities associated with complexity awareness and sustainable attitudes include meta-awareness or meta-cognition—the capacity to be aware of awareness or to think about thinking—and cognitive flexibility: the ability to readily switch attention between concepts, and comprehend multiple concepts simultaneously. In particular, these cognitive capacities support our ability to intentionally switch perspective, and evaluate competing paradigms.

Meeting the complexity of our times means more than achieving hyper-rationality. Cognitive scientists describe another innate ‘mode’ of mind, deprioritized by modern life, that comprehends relatedness and enables us to perceive the world as interconnected and whole. Indigenous teachings are grounded in this more direct awareness of interdependencies – and contemplative practices tend to develop this capacity for nonlinear, ‘holistic-intuitive’ cognition.

Activating Imagination and Unleashing Possibility

The great instrument of moral good is the imagination. – Percy Bysshe Shelley

Imagination has a profound part to play in systems change, but is easily overlooked. Often confused with fantasy or frivolity, imagination can be dismissed as a distraction from what’s ‘real’ or serious. This is a mistake, however: imagination underpins our ability to understand our reality and envision the future – a vital inner capacity to enable outer change.

Implicit in systems of meaning outlined above, imagination is foundational to beliefs, identity, values, and what we consider important and sacred. As Iain McGilchrist outlines in his hemispheric theory, imagination (paired with intuition) is another way of perceiving the world – complementary to science and reason. Imagination underpins sense-making; helping us model uncertainty, relationships, complexity, and paradox.

Imagination is a core component of empathy – enabling the ability to ‘step into somebody’s shoes’. It helps overcome heuristics such as salience bias and hyperbolic discounting to expand circles of care and responsibility to include those distant in time and space. Integral to ethical decision-making, moral imagination includes the ability to evoke the perspectives and experiences of other beings, foundational to action on behalf of, for example, future generations, other cultures, and other species.

What we can imagine influences what we believe is possible – and vice-versa. Addressing global crises and building a viable, life-sustaining society requires the ability to envision possible alternatives. Imagination is a basis for positive agency, building motivation to act before a crisis enforces reactivity. This kind of agency is rooted less in linear plans for the future than openness to present possibility and creativity; sometimes described as the ‘art of the possible’. Futures methodologies use cognitive and embodied exercises to help scaffold different visions of the future.

Metaphor work, myth, and immersive storytelling can access different parts of the brain, allowing people to experience different ways of being, perspectives, and scenarios. The arts have always played a profound role in shaping these channels of collective imagination; and popular culture, from films, theatre, and music to fiction, news stories, cartoons, and social media, remains pivotal in activating shared values and visions for the world. Art furthermore has a crucial role in shaping our notions of beauty and the desirable – an aesthetic that valorizes the beauty of, for example, equality, balance, consumer-restraint, and sacrifice could be a precondition for entrenching behavioral norms aligned with these values.

Promoting Resilience; Mitigating Threat Response

I can be changed by what happens to me. But I refuse to be reduced by it. – Maya Angelou

Awareness of ecological breakdown and threat to life contributes to widespread and serious climate distress – most acutely amongst young people. Those working in related fields shoulder a heavy emotional burden, contributing to reduced effectiveness and burnout. More generally, young people worldwide are experiencing unprecedented levels of mental ill-health. Difficult emotions are normal when processing adversity and represent a healthy response to unhealthy societal conditions. They shouldn’t be hastily pathologized or ‘treated’. However, persistent distress can harm health, reinforce unsustainable behavior, perpetuate denial, and inhibit climate action across society. As climate impacts intensify, strategies for adaptation and system change cannot ignore the role of psychological resilience.

Resilience involves more than recovery, entailing adaptability and even maturation amid change; sometimes associated with ‘post-traumatic growth’. Evidence-based practices can support the cultivation of this natural capacity. Public acknowledgment of citizens’ distress and efforts to address resilience furthermore present important routes to broadening climate discourse and motivating collective action.

Interrelated with both individual and community resilience is the neurophysiology of humans’ response to threat. Threat response is governed partly by underlying brain-body states; patterns of nervous system activation that motivate us to seek safety – often summarized as ‘fight/flight/freeze’. Although adaptive in our evolutionary landscape, in today’s world fight/flight responses can inhibit empathy, contributing to extremist views, ‘othering’ dynamics, and social tension. The ‘freeze’ response can be equally maladaptive. Indeed, neuroscience suggests that passivity might be a default response to prolonged difficult events, and that a sense of agency in this context must be actively learned, with important implications for climate action.

Individuals and groups may furthermore become inclined towards or even ‘stuck’ in patterns of threat activation through traumatic experience. Approaches that allow individual, collective, and intergenerational trauma to be acknowledged and healed have much to contribute to social cohesion and collective action.

Our social environment impacts our nervous system in turn – for example, antagonism within a group can raise nervous system activation for individuals. Without resilience strategies, challenging experiences can thus contribute to a vicious circle of increasing reactivity and declining well-being and social trust; a dynamic of particular relevance to Earth for All’s current models. Conversely, where better mental health support and higher individual resilience reduce threat reactivity, communities are less susceptible to fragmenting effects of polarization and radical populism, supporting group resilience, with important implications for sustainable behavior. Such cycles demonstrate strikingly the interconnection of individual, societal, and planetary health.

As Earth for All highlights, social trust arises from trustworthy social organization; and is naturally intertwined with economic factors like inequality. Citizens should not feel unduly responsible for their own well-being in poor conditions. However, amid compound crises, humans also need strategies for resilience less dependent on particular material circumstances, to protect well-being and cohesion and avoid worsening vicious circles. Alongside the case for economic reform, evidence-based psychological approaches and investment in strengthening the community can help counteract reactive and avoidant tendencies, nurture connection, and restore social fabric in the face of profound uncertainty.

Cultivating the Heart; Embodying Connection

What really counts in each of us and in our lives are the bonds of love – which can make one’s life not an episode but part of a larger continuum. – Aurelio Peccei

Among the dubious legacies of the Enlightenment worldview in today’s policy thinking is a tendency to deprioritize qualities of the heart that have bound societies together across millennia. However, the ‘Selfish Gene’ theory is waning in influence and more holistic, contemporary accounts of evolutionary biology and human history demonstrate that our unparalleled capacity for collaboration has been equally if not more important to our ‘success’ as a species. In particular, qualities such as love and compassion are ‘negentropic’ in human systems – cohering forces that create order out of chaos.

What we learn to value or love, and the depth to which we love it, shapes our world. And from Gandhi to Che Guevara, revolutionary leadership has long been “guided by a great feeling of love”.

Most religions treat love as sacred in some way: fundamental to divine nature, and usually to human nature. True to rationalist-materialist thinking, however, a quality once held most transcendent and ineffable is often treated by secular society as one transitory emotion among many. Love may be the most powerful intrapsychic force we experience, yet among the least researched or discussed in the context of politics, system change, or sustainability. As such it remains one of the greatest forces for change yet to be properly unlocked in human systems. In the political sphere, a platform of ‘Radical Love’ has recently been championed as an antidote to polarizing narratives and populism; and had its first major political success in the Istanbul mayoral elections of 2019.

Although love remains a tricky subject for science to pin down, qualities of heart including compassion, empathy, and ‘kama muta’ (the feeling of being deeply ‘moved’) have been more thoroughly researched and are associated with social change and sustainability mindsets and behaviors. For example, empathy has been found to increase sharing behavior in economic interactions, whilst increased compassion strengthens belief that humans are causing the climate crisis, and boosts sustainable decision-making and support for climate change mitigation policies. Compassion is also associated with overcoming the bystander effect—bias against intervening in critical situations when other observers are present—currently rife across the planet.

Such emotional capacities can be actively undermined or intentionally nurtured, with civilizational impact. Many evidence-based practices can support us to restore attention to what’s really important to us, and cultivate innate capacities of the heart and the values that mutually reinforce them. In cultures influenced by Modernist separation of mind and matter, developing body awareness is foundational in cultivating these embodied qualities – for example, body awareness is a precondition for empathy. Heart qualities are also supported by a social environment that habituates connection. Widespread isolation from others and from nature is at the core of our crises, and considerations of community bonds, embodied nature connection, and other relational practices are imperative in system approaches.

Wherever a rationalist paradigm is dominant, the driving role of emotions of all kinds in decision-making can be drastically underestimated. Adequate systems understanding depends therefore on cultivating the related capacity for emotional intelligence, which is likewise a vital foundation of collaboration and collective action.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Return to Volume 24 Issue 4, Collective Mind of Peace

The Club of Rome is a platform of diverse thought leaders who identify holistic solutions to complex global issues and promote policy initiatives and action to enable humanity to emerge from multiple planetary emergencies. The organisation has prioritised five key areas of impact: Emerging New Civilisations; Planetary Emergency; Reframing Economics; Rethinking Finance; and Youth Leadership and Intergenerational Dialogues. LEARN MORE