DESCHOOLING DIALOGUES

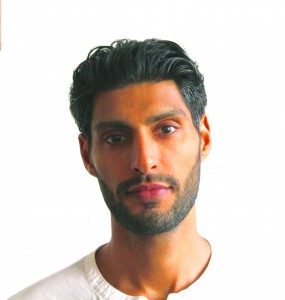

Episode 3 – Alnoor Ladha with Sophie Strand

In this episode of Deschooling Dialogues, host Alnoor Ladha talks with Sophie Strand. She is a writer based in the Hudson Valley who focuses on the intersection of spirituality, storytelling, and ecology. But it would probably be more authentic to call her “a neo-troubadour animist with a propensity to spin yarns that inevitably turn into love stories.”

Her first book of essays, The Flowering Wand: Lunar Kings, Lichenized Lovers, Transpecies Magicians, and Rhizomatic Harpists Heal the Masculine is out now from Inner Traditions. Her eco-feminist historical fiction reimagining of the gospels The Madonna Secret will also be published soon. Her books of poetry include Love Song to a Blue God (Oread Press) and Those Other Flowers to Come (Dancing Girl Press) and The Approach (The Swan). Follow her on Facebook or on Instagram @cosmogyny.

AL | Welcome to the Deschooling Dialogues. This podcast is a co-creation between Culture Hack Labs and Kosmos Journal. Culture Hack Labs is a not-for-profit advisory that supports organizations, social movements and activists to create cultural interventions for systems change. You can find out more at culturehack.io.

Post-production is made possible by the dedicated supporters of Kosmos Journal, focused on transformation in harmony with all Life. You can find out more at kosmosjournal.org. And thank you to Radio Kingston for the use of this space today. I’m your host, Alnoor Ladha.

I’m here with Sophie Strand, who’s a dear friend, sibling, an inspiration when it comes to weaving words and worlds. She is a writer, a compost heap, a troubadour, an animist, and she’s the author of the Flowering Wand, which is out now, and Madonna’s Secret, which is coming out this summer. Welcome to Deschooling Dialogues. Thank you for being with us and taking the time.

SS| Thank you so much for having me and for having my little dog who may vocalize during this.

AL | So let’s start with a little bit about the inquiries you’re holding now and a little bit about the journey.

SS | A little bit about the journey. I was raised in a swamp of Theravada Buddhist monks, rabbis, theologians, rescued possums, raccoons, mountains. My parents write about the history of religion and they also write about ecology. So, I definitely have a root system in these things and was produced by dinner table conversations that range from eco-anarchism to the history of Christianity.

SS | A little bit about the journey. I was raised in a swamp of Theravada Buddhist monks, rabbis, theologians, rescued possums, raccoons, mountains. My parents write about the history of religion and they also write about ecology. So, I definitely have a root system in these things and was produced by dinner table conversations that range from eco-anarchism to the history of Christianity.

These days, I’m thinking a lot about healing paradigms and how they’re helpful and how they also constrict us and foreclose certain possibilities for wellness. And I am looking at my own story with chronic illness and with trauma under a different lens, under a more interspecies lens, trying to problematize the ways in which I have focused on the human when it comes to healing instead of my wider connectivity. What are you thinking about right now? I know you just finished a book on philanthropy, composting philanthropy.

AL | Kind of against my will. Yes. I think a lot about post capitalism, not in a temporal sense of what comes after this existing system, but more about what are the enabling conditions to create embodied cultures worth living. And I see a lot of parallel between our work in the sense that you often go to ecology for your inspiration. We were talking about pigweed the other day, and you gave me the metaphor of pigweed, and I thought, wow, that’s a post-capitalist being, the pigweed. Maybe you can say a little bit about it.

SS | So a little context, my grandmother was an English rose gardener, and she didn’t know better, and she used glyphosate in her rose garden, and she died of complications from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which is now shown to be directly caused by glyphosate, and posthumously she was included in the class action suit against them, and I think a lot about it. She was the person who I felt closest to. She lived with us as she died. I loved her quite a bit. She was a gardener and a lover of plants, completely pagan without knowing that that’s what she was. And I think about how we are all threaded through with microplastics. We’re all drinking water with blood pressure stabilizers and pesticide in it and experiencing auto-immunity and cascading physical glitches that of course, the environment is also experiencing at a much higher degree.

And for me, I was thinking, I can’t purify myself. I can’t put myself into some machine that purifies my blood and fixes me. I need a good metaphor. And so, in medieval England, there were cults of saints and it seemed Christian, but really, they were syncretic with much earlier tutelary land deities. So certain plants, certain springs, certain valleys would have healing attributes, and they became conflated with Christian saints so that they could still exist within the oppressive paradigm of colonial Christianity. But they pointed to plants and animals and places that could heal you. So, you would pray to a certain saint for a toothache, for a fever, for heartache. And so, I’ve created my own cult of saints, but they’re all plants and animals and microbes, and they’re the plants and animals and microbes that are, as you said, post capitalist; ones that are not the master’s tools.

“The master’s tools will not dismantle the master’s house” [Audre Lorde]. They’re always the dirtiest, most hated beings. And one of those is pigweed. And pigweed is a weed – it’s actually indigenous to America, but we treat it like an invasive species because it destroys our monocropping. It’ll get into a field. They have these deep tap roots that are impossible to get rid of without something called flame weeding where you burn down the entire field. And the best thing is they genetically outpace pesticides that they can outpace glyphosate in one generation.

AL | As their adaptive mechanism.

SS | And so they can metabolize the pesticide and learn how to get rid of it immediately. And so I started praying to pigweed just to teach me how to alchemize these poisons in my own body. So that’s one. But I like calling them post capitalism, like co-conspirators.

AL | They’re sort of apocalyptic, but also post capitalistic deities.

SS | Yeah. Do you have one right now? Can you think of one?

AL | The one that comes to mind, and you’ll probably know the Latin names better than me, is the particular fungi that infects the ant.

SS | Ophiocordyceps unilateralis.

AL | There you go. I knew you would. And why I think the metaphor is so interesting is that it doesn’t have a body in that sense. It can’t get to the top of the tree, but it can infuse the ant’s body and become a symbiont with the ant. And the research on it is really interesting because they don’t know if it’s affecting the neurology of the ant; if it’s happening at a strictly neurochemical level, like the ant is high. They haven’t figured out what the mechanism is; in which way is it doing this. And I think in some ways that the kind of post capitalist resistance is like what we have to ride the bodies of – in some ways, more mobile, more superior creatures and take root in logic like that.

SS | Yeah. I love that metaphor too. I often think of that ant when I think of art, which is ‘good art is never you’. It’s always using your body and hijacking you to do something that’s bigger than you. And that experience is usually terrifying. We do not know what that ant is experiencing, but I think Merlin Sheldrake says by the time the ant’s at the top of the plant, it’s a fungus in an ant costume, which I love. How can we become fungus in human costumes and trees in human costumes? How can we let ourselves be colonized by these beings?

AL | For me, this kind of line of thinking comes with the idea of purpose. I think a lot about how, in the living world, no species requires purpose or is contemplating their purpose or is navel gazing about its purpose. And the West is obsessed with it. From career counselors to the kind of Fordist procession that moves us towards some kind of vocational job. When you’ve come out of high school and you get these seven bad options of architect, lawyer or doctor or whatever, before we even know what we are orienting towards. A plant understands photosynthesis. It has its teleology if you will, intact. And we’re so rudderless, especially in a culture that tells us a kind of materialist reductionist fallacy of acquisition is going to somehow save us. And the only thing we need to do is whatever’s required to get us into a relatively hierarchical position to acquire more, consume more, validate more, et cetera.

SS | I was thinking about accumulation. We want to accumulate as much as possible, put as much into our bodies. And by extension, we’re making as much land into places to grow our food, our monocrops, or our cows and our chickens, which are an extension of our own bodies. But I often think of these spiders that always die when they reproduce, or they will jump into the mouths of these giant female spiders and die.

There were these rare spiders in this zoo, and they were trying to get them to reproduce, and they were waiting and trying to make sure that the lady spider didn’t eat him before they mated. And she ate him and everyone despaired because they were the last of their kind. And then two weeks later, she was pregnant. He managed to, as he was dying, do the act. And for me, I was always thinking, we think that that’s a life wasted. We think we have to save life, but life doesn’t have a savings account. It spends everything at once always.

AL | And maybe there’s a transition between these two. I think I told you about my uncle before. I remember being about 17 years old, and the career counselor or whatever they called them back then, gave me all this propaganda for Canadian universities. I’m looking at this and my uncle walks in the room and he’s like, ‘what are you doing?’ And I said, well, I have to pick what university I want to go to. And then he just sort of laughed and he was like, ‘you’ve become so colonized.’ And then his line was, ‘your life is a consequence of your prayer.’

SS | Beautiful.

AL | ‘Your life is the consequence of your prayer.’ You don’t like your optionalities, you don’t like your choice set. Go to your altar, go do your Dhikr, which is Arabic mantra, refine your prayer, and then you can negotiate with Life again. And it just recalibrated the way I was approaching this limited choice set of what I could do and what my purpose was. There is no purpose. There’s only prayer, and you’re in dialogue with this animate world. There’s a pathway in death also because I think death-phobia is driving most of our motivations at a civilizational level. It’s obvious, when we look at healthcare for example, or end of life care, palliative care, and Elon Musk wanting to go to Mars and uploading our consciousness to the AI and all of that, but also at a daily kind of quotidian way, our purpose and death are so entwined.

SS | Well, I think it’s interesting. I was just thinking of this great line from my favorite Linda Hogan poem, which is “to enter life, be food”. I think maybe the most terrifying thing is to really realize what our purpose is, which is to be food, to ‘become food’, to make ourselves edible. How do we make ourselves edible? It’s not about being a doctor or doing anything of the sort. It’s about making sure that at the end of our lives we could be eaten. And that’s very terrifying. That’s so closely wedded to death.

SS | Well, I think it’s interesting. I was just thinking of this great line from my favorite Linda Hogan poem, which is “to enter life, be food”. I think maybe the most terrifying thing is to really realize what our purpose is, which is to be food, to ‘become food’, to make ourselves edible. How do we make ourselves edible? It’s not about being a doctor or doing anything of the sort. It’s about making sure that at the end of our lives we could be eaten. And that’s very terrifying. That’s so closely wedded to death.

I often think that our fear of death is also closely linked to our weird relationships to food webs. That food webs are created by waste, by delicately plugging your waste into another being’s appetite. That’s how the nitrogen and the salmon make it all the way into the rivers, then into the bear’s bodies from out in the ocean, that the ocean is tied in deep, deep miles into the land by these salmon and by their waste decaying and being eaten by bears. And then the bears are pooping on the shore of these rivers. We don’t know how to make our waste edible anymore. We don’t know how to make our death edible. So I sometimes think that my purpose in life is just really simple. It’s very material. How do I make sure that at the end of my life I can be eaten?

AL | There might also be an esoteric layer to this. I was thinking of Zhenevere Sophia Dao, who said, on multiple occasions, ‘I try to cultivate my diet so I’m erotically attractive to Gods and deities.’ It’s a very Dao conception of death – you cultivate your qi in a certain way that the more-than-human and these multidimensional beings are attracted to you.

SS | I often say to people, we have to realize that we are not just speaking with our mouths, we’re speaking with our whole bodies to other beings. So, the first way we usually speak to other beings is with our smell. And we have forgotten. We are very loud with our smell and unintentional. And the truth is that we’re eating processed food, we’re covering ourselves in synthetic chemicals, and then we’re quietly going into the forest. It’s a very loud, unintentional entrance. If you’re smelling like that, I often think that the first way we can key into how we’re communicating with these other animate forces is through smell. Can we learn to smell better? Can we learn to speak better with our whole bodies?

AL | Which happens through diet. And in the Daoist sense it happens through spiritual practice, vis-à-vis this idea of death. I was also thinking of something you said in our conversation with V [formerly Eve Ensler – see bonus episode with Sophie Strand and V] which is “we’re not children of the garden, we’re children of the crater”. And what comes to me, and I’ve had discussions around this in other contexts, is 99.9% of every species that’s ever existed on the planet is no longer with us. So, the scientific analysis of 10 to 60 million species that are alive on the planet are only less than 0.01% of all life that’s ever lived. And so maybe the point is not perpetual existence, but to die well. It’s actually extinction. That’s what life moves towards.

SS | Or combining bodies. I mean, I oftentimes think that the most biological novelty are the moments when two species are like, ha, we’re done. Let’s just combine. Let’s burn the bridge to our old body behind us. Two simple prokaryotes used to create eukaryotic life; botched cannibalism created our bodies. So yeah, we’re also, maybe right now we’re being asked to jump into other bodies, and that does seem like death and probably feels like death. It’s like the fungus in the ant.

AL | We also don’t know what we’re becoming. We think evolution is a finite force that has a destination. But we have no idea. We’re still navigating our own verticality.

SS |I know. And we don’t do it well. I mean, Thomas Halliday, this great paleontologist says something that is like my prayer – it’s ‘nature is not nostalgic. It’s creative.’ It will put new things together every day to keep life moving. It’s not devoted to one species. I always say, ‘matter is not species monogamous. It’s promiscuous.’

AL | I love that.

SS | It moves between bodies and it changes bodies to keep moving. Yeah. I hope that whatever happens, I contribute to ‘the commons of the general enlivenment’, to paraphrase Andreas Weber. I hope that’s how you say our friend’s name. But yeah, I hope I can pay forward my matter to the general aliveness.

AL | In terms of death, dying, extinction, eukaryotic life, this sort of symbiont, holobiont and cyborg beings that were becoming in some ways, what is your sense of the directionality?

SS | What is my sense of the directionality? My sense of the directionality is I’m an ant on a very big earth, and I have no sense of the direction. I just hope that I will make myself a doorway through which matter can flow without being blocked. And we were talking with V earlier about the ones who walk away from Omelas, which is this utopia that is justified and kept in place by the abuse of one child.

AL | This is the Ursula Le Guin short story.

SS | And the direction is not what matters. The important thing is to walk away, I think, ‘what’s the direction we’re moving in?’ Is it towards complete extinction? Is it towards some weird kind of digital Symbiocene? Is it towards the grid going down? I don’t know. All I know is that I want to walk away from Omelas, and I hope that I can join hands with other beings, be they dogs or plants or trees or friends like you, as we choose to walk away. So what direction are we moving in? I hope we are moving away from Omelas.

AL | In some ways, we are walking towards the event horizon, whatever’s coming. Terence McKenna always used to say that ‘we are in parking orbit of this event horizon’. We sense it, it’s around the corner. And it feels like, on one level, there’s this digitization that’s happening from crypto wallets to vaccine passports to AI that’s happening in one direction and then in the other, you have to choose between becoming cyborg or free people.

SS | I know. Yeah. I mean, the one thing I think about, and I’m interested to hear where you’re learning right now. I do think that we treat this technology like it is a God, and we forget that it’s made of very fragile materials and materials that depend on our supply chains and our infrastructure holding. Most of our technology depends on one factory in Taiwan making these computer chips and our relationship with Taiwan being okay. I sometimes think that we’re in a kind of weird medieval theological relationship to technology that doesn’t actually admit that it’s fragile and it needs a lot of parts still working. I think it’s too fragile to be our future, personally. How do you feel?

AL | Yeah. All this talk about AI singularity, I find on some levels quite ridiculous. This requires the perpetual mining of lithium from Bolivia. And coltan and cobalt from West Africa, that’s not going to happen. And it also requires huge amounts of satellites in the air and a global energy grid. And we’re mitigating for a three degree rise in temperature by mid-century, which is correlated with 40% biodiversity loss. That’s like 40% of all life not being here. We have no idea what’s going to happen to the ecosystem and the biome and the web of life. And it’s also correlated with the 10-to-20-meter sea level rise.

SS | There’s no way these things are going to keep in place.

AL | And then the other aspect of this is also the belief that you can get consciousness from non-consciousness makes no sense to me. Neuroscience has spent 30 years trying to figure out the hard problem of consciousness. And the reason it’s a hard problem of consciousness is that their logic is circular.

SS | It’s a black box with this homunculus inside of it that’s operating this other homunculus…

AL | And the analysis that it’s an “emergent phenomenon”, that mind, that consciousness itself, just emerged from this machine called the brain. And this is also related to nostalgia, right? Because we are told that the human neocortex is the most evolved thing, and what will happen if the universe doesn’t have it?

Consciousness is distributed. It’s everywhere. It’s in everything. And if that was your starting place, if we had a more idealistic, pan-psychic starting place, you wouldn’t have the hard problem of consciousness. And you also wouldn’t have the fallacy that somehow AI consciousness is going to be created from nothing. When we don’t even know how consciousness in the human brain works, how are we now going to bestow that God-like ability on ones and zeros and digital machinery?

SS | I’m deeply of a kind of new materialist, pantheist, animist sensibility. My sense is that, yeah, these machines and bots are sentient, but they’re sentient because they’re made from material that’s sentient and they’re not sentient because we’ve created some neural network. They’re sentient because matter is bumptious and agential in ways that we cannot control and conceive of. And one thing I am not worried about, but very aware of, is I think that technology is haunted. I think a lot about how a lot of medicine depends on Nazi experiments that have just dropped out of the footnotes.

Can you separate the means from the ends? What does it mean that most of our medical science is done from experimenting on animals? We think about quantum entanglement, we think about the observer always affecting the outcome. I always think that when you kill one being, that affects the outcome. What does it mean that our medicine is based on this erasure, this illusion? And so I think a lot about how the AI we’re creating is haunted with materiality, with minerals and stuff that’s been extracted from the earth. What does that material want? That’s the consciousness we’re talking about and not acknowledging,

AL | Right. There’s the Donna Haraway line where she says, “it matters what matter we matter with.”

SS | Yes. It matters what stories we use to tell other stories.

AL | What ties we tie knots with.

As this focus of this conversation is on deschooling, and I love that we have our non-linear weaving and we’ve talked everything from purpose to the body to AI. What do we need to unlearn as a culture in order to be good compost, in order to be useful to the aliveness of matter?

SS | Well, I want to hear your answer. I think the thing that I’m pretty focused on is we need to unlearn the atomized self. We need to unlearn the sense that there is an individual. We only come into being through interface and through relationships. Healing doesn’t happen in one body. It happens in a meshwork of bodies. Trauma doesn’t come into being through perpetrator and victim. It comes into being through complicated systems of complicity. So I think for me, the thing I would like to unlearn is this sense that I am a self with boundaries that should be defended. I need to get used to an idea that I’m leaky and that avails me to pollution and harm, but also of more nourishment and feral ways of surviving than I could ever have expected. What do you think we need to unlearn right now?

AL | I’m totally with you. I think at the highest level, when we try to get to the root, in through root, with the root, we could say the root is neoliberalism or the Neolithic revolution or the invention of the city state. We can try to historically and anthropologically go back to the materialist driver. But what it comes to for me is the illusion of separation.

I love this definition from chief Niniwa [of the Huni Kuin people from Acra, Brazil], colonialism and whiteness are the illusions of separation as neurological cultural impairments. That we’ve internalized this belief of separation so deeply that it affects our very ontology, and ontology is the applied philosophy of being. And sometimes it’s interpreted as vision, literally the way we see the world. And so if my gaze is structured in a way that everything is separate and materialist and reductionist, I’m therefore entitled to manipulate the world as I want. I think that becomes the root of so many of our societal illnesses.

The belief that we’re separate from other beings also requires a deep numbing and anesthesia of the body and the soul and the mind and the heart complex. Because how could you treat another being in these ways or accept the living conditions of other human beings or the widespread destruction of the ecology unless these aspects of you, that know are not separate, are put to sleep.

SS | Exactly. I mean, when you realize that all of these arrows you’re shooting are going into your own breast, you’re going to feel a lot of pain. I mean, the thing I think about a lot is there’s a rather precious take on ecological embodiment right now that it’s about covering yourself in olive oil and sluicing yourself with the dirt.

SS | No, it’s just that we need to go out and participate in nature. But the truth is that the threshold you have to cross is that it’s like when your foot has been asleep and it comes back awake, that hurts. It prickles when you realize that you’ve been hurting yourself, your extended body for such a long time. And I think a lot of us right now are navigating that pain of waking up from the numbness.

AL | Completely. And that part of me that is empathic and connected and in the non-separate state, those are the best aspects of me. And for them to be amputated and to be colonized in that way means that I’m not fully available to life itself. And so, I’m in this active practice of how do I integrate these various ignored, amputated aspects of myself to be in the state of non-separation? And again, I don’t think it’s an arrival place. But I am committed to that journey of whatever it takes. The feelings and the emotional experiences that come with experiences of non-duality and non-separation are much more interesting to me than any material comfort that stems from the illusion of my separate beingness.

SS | I mean, I loved the distinction you made earlier between the destination and the process. We’re so focused on the destination, we forgot how to keep moving. I always think that certainty is a bad flotation device, and it keeps you from learning how to swim. And the truth is you just need to learn to swim to move your muscles rather than depending on some kind of faulty false dualism or set of controls. How can we learn to just be in the process without trying to get anywhere?

AL | It’s practice and there’s a constant orientation that’s required to be like, oh, ‘I’m attempting to get somewhere’.

SS | Yes, no, you never get sober from it. I think that’s the thing that I’m realizing right now is like, any moment I think I’m sober from the culture, I’m the drunkest. In fact, saying you’re sober is a good sign that you’re pretty drunk. I think I’m just constantly realizing I’m an alcoholic. You’re never not an alcoholic in a 12-step program. You’re always an addict. And I think that’s the thing: I’m an addict of this culture, and I need to be actively aware of that and investigate how it infects every single one of my decisions as an addict. You can think, I’m just going to visit a friend on this street. I just love seeing that friend. I mean, it is next to my old drug dealer. You’re really good at hiding things from yourself. And so I think 12-step work is actually sometimes a really good way of thinking about how we’re addicted to the culture. And it keeps you humble.

AL | There was a line given to me by a plant much smarter than me, and she said, ‘ignorance is the seed of all ontology.’ And I asked her to repeat herself, and she said, ‘ignorance is the seed of all ontology’. That if you could even try to grasp the consequences of your ignorance, that becomes the seed of the way you see the world because it’s completely shaped by your ignorance. And then the next logical step would be that humility is the midwife to wisdom. There’s something very humble about walking around the world, acknowledging that you’re never sober, that I’m an addict to this culture.

SS | I think that’s my big work these days is just seeing the moments when I begin to slide. And I think that’s always a big moment in an addict’s life is realizing the moments when your behavior begins to slant downhill. And we can all help each other. I mean, I do think that’s why group work is really important in confronting this. We can’t do it alone. We have to do it in conversation.

AL | That’s a beautiful way to end or begin and always be in the middle. And yes, we stay in the middle. Thank you so much, Sophie. Thanks for spending the time and it’s good to do it in your hometown.

SS | It feels really special. Thank you so much.

AL | We’ll see each other soon. Thank you.